The untold, bloody origins of US Independence Day

BBC

BBCAs a Brit, I didn't learn about the American Revolution in school. But my children all grew up in the US – and they did. And I noticed that while the Civil War is often portrayed in all its violence and gruesomeness, stories from the revolution focus on heroism.

When I think of the American Revolution, my mind conjures images of impassioned colonists dumping tea into Boston Harbour. Paul Revere's midnight ride through Massachusetts. George Washington crossing the Delaware River. America united, alone and in the right.

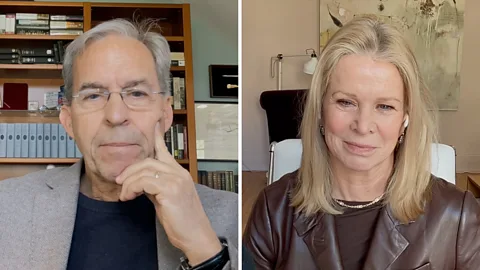

But 250 years since the war began, it's time for a different, more complex look at America's origin story. I recently spoke with Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Rick Atkinson about the realities of the Revolutionary War that often go overlooked. His latest book on the conflict, The Fate of the Day, comes out later this month on 29 April.

It was an eye-opening discussion that taught me a lot – you can watch or read our conversation here:

Below are excerpts from the above conversation, which have been edited for length and clarity.

Katty Kay: It wasn't until recently that I really became aware just of how gruesome the Revolutionary War was. One in 10 Americans who fought in it died, as you recount in your book. The stories from the Battles of Saratoga of 16- and 17-year-olds freezing to death in the fields. I was wondering why you felt it was important to tell that side of the story in your books.

Rick Atkinson: The revolution has kind of a faded lithograph quality to it. The blood has been leached out, but it was a terribly bloody affair. There were at least 25,000 Americans, maybe as many as 35-40,000, who died. That's a larger proportion of the American population at the time to die in any of our wars other than the Civil War. I think the reason that it hasn't been acknowledged to be the bloody affair that it was is in part because of distance. 250 years of distance makes it hard to really feel an emotional connection to the dead. The Civil War, for instance, has photographs of the dead at places like Gettysburg and Antietam. There's none of that in the revolution.

KK: I can see why there was a need in the Revolutionary War to build up the founding fathers into almost Greek gods. Do you think they were sort of put on a pedestal because America needed that as the kind of launch pad of its narrative?

RA: Yeah, I think that's true. When you've been through an ordeal like the eight-year revolution was, there's a natural sense of believing that those are demigods who managed to win through. But George Washington had feet of clay like all of us do. He had almost 600 slaves at Mount Vernon during his lifetime. It is an awful reminder that the prosperity of this country was largely predicated on bondage.

The propagandists who were running this country at the time were so effective as propagandists that they had really portrayed the British as evildoers, even though there were atrocities committed by both sides. If you were a loyalist in this country, you were subject to expropriation, jail without a bond, torture and sometimes even execution. We kind of whitewashed that part of the revolution for years, decades, centuries even. We haven't fully acknowledged it, I think, even today.

KK: One thing that you make very clear is that there weren't just two sides in the Revolutionary War; there were actually many sides. There were Americans who didn't want to be independent. Americans who just didn't want to fight. Americans who thought of themselves as British. Benjamin Franklin's own son didn't want independence. Again, I come back to the idea that the story is muddier, perhaps, than we were told for a couple of centuries.

RA: It makes it a much more interesting story. Benjamin Franklin's beloved son, William, was the royal governor of New Jersey. He got the job partly through his father's influence. And he just refused to buy into the notion that rebellion was legitimate. And he went to jail and eventually into exile. You multiply that by thousands and you see families split apart the same way they were in the Civil War.

The Civil War qualities of the revolution extend in other ways. The Six Nations of the Iroquois had gotten along very well for more than a century. And the revolution forces them to choose sides. Four of them align with the British and two with the rebels – and they're killing each other.

This is one of the aspects of the revolution that I think has not been fully appreciated by us in our history: the extent to which the war was not just between us and them, but us and us – on several levels.

KK: I was talking to historian and filmmaker Ken Burns recently about the revolution and he compared the intense divisions in the colonies to South Vietnam during the Tet Offensive. I'm wondering whether you feel that understanding all the muddiness and complexity of the revolution makes the war feel more relevant to a modern audience.

RA: I think when you look at America in 2025 and see these fractious people, you can follow that thread right back to the beginning of the origins of the country. We are a fractious people. We are a bellicose people. We are a violent people. It's not easy to acknowledge. We like to think of ourselves as peacemakers and a force for good, but that is not the only thing we are. I think that understanding who those people were and how difficult they could be at times can help us to reconcile ourselves with the people we are 250 years later.

KK: I also think there can often be this origin-story idea that America did it mostly alone in the Revolutionary War. But your book starts with Benjamin Franklin asking for support from the French. Was that sense of doing it alone something that you were conscious of revisiting when you wrote the book?

RA: Yeah, because otherwise it's not a true story. We don't win the war in 1783 without the French. Franklin's job is to persuade Louis XVI that France – an absolute monarchy, a Catholic monarchy – should throw in its lot with Protestant, rebellious, Republican wannabes.

KK: Okay, put like that, I see the diplomatic challenge.

RA: It took him years! But he was very gifted, and he persuaded the French that joining the war was in their best interest, because the French had grievances against the British. And then, the Spanish come in with support. And then, the Dutch come in. America needed help; that's an important part of the story. When we give a thumb in the eye to our closest friends today, we should remember that we've needed those friends in the past. We will need them again in the future. It's a lesson directly from American wars in the past, starting with the revolution. Winston Churchill said that the only thing worse than fighting with allies is fighting without them.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.