Hotdogs and motorways: The ripples created by Denmark's Ozempic and Wegovy boom

Adrienne Murray

Adrienne MurrayAmerican demand for weight-loss drugs is supercharging Denmark’s economy and transforming a small Danish community into an unlikely boomtown.

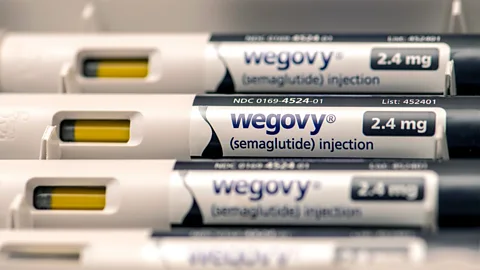

Look back only two years ago and the name of Danish firm Novo Nordisk would hardly ring a bell. But now, soaring sales of two blockbuster drugs, the anti-obesity and diabetes treatments Wegovy and Ozempic, have turned this pharmaceutical giant into one of Europe's most valuable companies.

The drugmaker revealed in early February 2025 that its pre-tax profits jumped 22% to $17.8bn (DKK127.2bn/£14.2bn).

It has also given Denmark's economy a huge boost, making it one of the region's fastest-growing. From new job creation to lower mortgage rates, the ripple effects of skyrocketing drug demand have been felt across the country, and not least in the tiny port town of Kalundborg, a community of fewer than 17,000 residents, where one of the biggest investments in Danish history is now underway.

Stepping off the train on the outskirts of Kalundborg, an hour northwest of Copenhagen, passengers are greeted by birdsong and construction noise. It's an unlikely spot for what is now the epicentre of a global weight-loss revolution.

Across a railway bridge stand the grey, boxy buildings of Novo Nordisk's sprawling industrial site. This is where half of the world's insulin is made. It's also where semaglutide is produced, the game-changing active ingredient in Ozempic and Wegovy.

"We are the centre of where the medicine starts, the core substance," Kalundborg's mayor Martin Damm told me, as we toured the plant's perimeter, a vast site covering 1.6 million sq m, equivalent to the size of 224 football pitches.

"Now you're coming into crane land," announces Damm. I quickly counted about 20 of them towering over new concrete structures and temporary cabins.

An eye watering $8.6bn (DKK60bn) will be spent here over the next few years, which will see 1,250 new jobs added to the plant's 4,400-strong workforce. It's also brought 3,000 construction workers to the area. "We have a rule of thumb, when you have one job inside the industry, that will generate three jobs outside," stated Damm.

Kalundborg's economy has seen ups and downs. Once a shipbuilding centre, it then boomed in the 1960s manufacturing Carmen Curlers, a hair roller that was popular in the US until fashions changed. Now it's seemingly on a roll again.

As we drive by, Damm points out a petrol station. "Every morning the owner needs to roast 30kg (66lbs) of pork to make sandwiches. All these craftsmen like pork sandwiches." There are more boom stories: a local supermarket has seen sales increase five-fold and a fast food store sold 17,500 hot dogs in little over a month to hungry construction workers seeking an easy lunch.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTwo-thirds of Denmark's GDP growth came from just four boroughs. All share one thing in common: they're where Novo Nordisk premises are located. Among them Kalundborg saw a staggering 27% growth rate in 2022, according to the most recent data available. "We were number one," says Damm, adding that unemployment in the area, once high a decade ago, is now among the region's lowest.

Novo Nordisk's swelling corporate tax bill has lifted the municipality's finances, which has splashed out on a public swimming area, and plans for a new culture house and library. More than 1,250 homes will be built, and ground has been broken for a new motorway to Copenhagen.

Yet despite this income, local primary schools lag behind on subjects like maths, and the area has a higher rate of overweight children, prompting some criticism.

Speaking to the BBC, locals in Kalundborg were measured about seeing the benefits just yet. "Businesses opening and closing, that's the same," says Lonny Frederiksen, who runs a hair salon in the town. "But young people have more opportunities today."

Many workers commute rather than living in Kalundborg, adds customer Gitte Pedersen, while lamenting the heavy traffic. "Sometimes I have to wait [because of the] queues and I don't like that." But she's optimistic about the town's future, "It will bring a lot of jobs. In a few years we'll see the difference."

Insatiable Demand

For a century Novo Nordisk's business was built on making insulin, but the discovery of semaglutide's weight-loss effect, marked a turning point. "It is really transforming into a new firm," says Kurt Jacobsen, a professor at Copenhagen Business School, who's authored a book on the company.

Wegovy and Ozempic belong to a class of drugs called GLP-1s, that help control blood sugar and suppress appetite. Ozempic got US approval in 2017, followed in 2021 by Wegovy, which is now available in thirteen countries, including China.

Sales of the weekly weight-loss jab grew 86 percent last year, while Ozempic is the world's biggest-selling diabetes medicine, and 45 million people now use the firm's treatments.

More than half of Novo Nordisk's sales were in the United States, where tens of thousands of new Wegovy users have signed up weekly for prescriptions. There it costs more than $1,000 (£746, €958) a month, compared to only $92 (£73/€88) in Germany, and many insurers refuse to cover it.

During a congressional hearing last year, Senator Bernie Sanders repeatedly asked Novo Nordisk's chief executive officer Lars Frugaard Jørgensen why Americans pay more, demanding the company "Stop ripping us off!" In response, the firm blamed the complexities and "middlemen" of the American healthcare system.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWorldwide around 800 million people live with obesity, and it's estimated the market for weight-loss treatments could be worth $150bn (£144bn) globally by 2030. That's fuelling an industry-wide gold rush as big Pharma search for the next generation of anti-obesity drugs. Novo Nordisk and American rival Eli Lilly, which produces similar medications, lead the pack for now, but both drugmakers have struggled to keep up with the insatiable demand. To boost manufacturing capacity, Novo Nordisk has embarked on a colossal spending spree costing several billion dollars. It's enlarging factories at home and adding a new plant, while beyond Danish shores, sites in France and the US are being expanded, and it bought three drug-making facilities from American firm Catulent.

A big impact on a small economy

For a company with its headquarters in a small nation with less than six million people, Novo Nordisk's rise has had an outsized impact. "There are other companies that also play a big role in the economy, Maersk especially, but nothing on this scale," says Las Olsen, chief economist at Danske Bank. "This is the largest ever."

In 2023 Denmark ranked among Europe's fastest-growing economies, as GDP expanded by 2.5%, and half of that was driven by the pharmaceutical sector. After a big boost from drug exports, the government now anticipates that growth in 2024 was 3.0% and will be 2.9% this year. It's also the country's largest taxpayer, and accounted for a fifth of all new jobs, while many Danes and pension funds hold shares.

"In a way Denmark is like the rest Europe, but a little stronger. Then with Novo Nordisk on top, we're a lot stronger,' says Olsen.

Dollars flooding into Denmark from overseas sales have put pressure on the krone. The knock-on effect is lower borrowing costs. "We have slightly lower interest rates than the euro area, which is a very direct result of all this money inflow," explains Olsen.

More like this:

Conversely, in recent months, the firm's previously sky-high stock price has been hammered, after trial results for two new anti-obesity treatments disappointed investors. It prompted a sell-off so huge that Denmark's currency briefly weakened. However, successful early trial data for another new weekly jab saw shares swing up again in January.

And there are concerns that Novo Nordisk is outgrowingDenmark and could make the economy more vulnerable. Comparisons have been drawn with Finland, where the economy slumped in 2007, as mobile giant Nokia failed to compete with new smartphones. But most experts here aren't too worried about a similar outcome.

"Most would agree that there is a low probability," says Carl-Johan Dalgaard, chair of Denmark's Economic Council. "Of course, the probability is not zero. If you have an economy that harbours industrial superstars most would find it a big plus."

However when a few large firms dominate a country's economy – and that's increasingly the picture in Denmark – there can be other drawbacks, suggests Dalgaard. "There's a worry that with economic influence, you might also eventually see political influence emerging, which could have policy consequences."

Adrienne Murray

Adrienne MurrayBut there are new risks on the horizon. Amid tensions over the control of Greenland, US President Donald Trump has threatened potential tariffs on Danish goods, and Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen recently summoned leaders of the country's biggest companies for a meeting. "It has been hinted at from the US side that there may unfortunately be a situation where we work less together than we do today," says Frederiksen.

Among those present was Novo Nordisk's Jørgensen, and following the company's earnings announcement on 5 February 2025, he told reporters the business was well-prepared, but "not immune".

"Tariffs are always a bad idea," says Jacob Funk Kirkegaard, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. However he reckons, "Of all the countries in the EU, nobody would be more resilient to US tariffs than arguably Denmark. A company as sophisticated as Novo Nordisk (which also has production outside Denmark) would be able to insulate themselves."

'In five years, it'll be totally different here'

Besides Novo Nordisk, a string of large international businesses have emerged from Denmark including shipping giant Maersk, brewer Carlsberg and toymaker Lego. Many are partly owned by charitable foundations. The model gives longer-term stability and prevents firms being easily broken up, says Mette Feifer, vice president of the Danish Chamber of Commerce. "If Novo Nordisk were not owned by a foundation, I don't think it would be Danish at this moment. It would have been sold 10 or 20 years back."

The company's philanthropic foundation is now the world's richest, and in 2023 it showered $1.3bn (£1bn/DKK9.1bn) in grants on hundreds of projects, in Denmark and beyond.

Back in Kalundborg a new educational campus has sprung up training the next generation of life sciences workers. Among several institutions, Helix Lab is financed by the Novo Nordisk Foundation, and gives Masters students access to research labs and placements with local biotech firms.

Adrienne Murray

Adrienne Murray"You have the industry right across the street, and you can collaborate more closely with them," says Maria Riquelme Jimenez, a chemical engineering student from Mexico, who hopes to eventually find work with Novo Nordisk.

"It really gives them an advantage for future jobs," adds Anette Birck, director of Helix Lab. It's also helping to attract talent and providing opportunities for Kalundborg's youth, she says.

Overlooking the town's smart waterfront sits Costa Kalundborg Kaffe, owned by New Zealander Shaun Gamble. "Driving through the building area, you just get surprised how massive it is for a small town," he says. His coffee shop has seen a pick-up in customers and he's noticed more international students moving to the area, as well as local businesses opening up. "There has been a change. It's still in its infancy, but I can feel it," he said. "In five years, it'll be totally different here – in a good way."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.