Chernobyl survivors assess fact and fiction in TV series

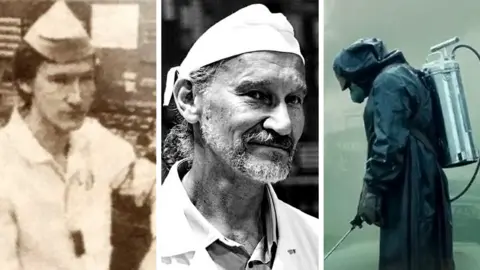

Moloda gvardiya/MICHAELA VONDRUSKA/SKY UK LTD/HBO

Moloda gvardiya/MICHAELA VONDRUSKA/SKY UK LTD/HBOHours after the world's worst nuclear accident, engineer Oleksiy Breus entered the control room of the No. 4 reactor at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine.

A member of staff at the plant from 1982, he became a witness to the immediate aftermath on the morning of 26 April 1986.

The story of the reactor's catastrophic explosion, as told in an HBO/Sky miniseries, has received the highest ever score for a TV show on the film website IMDB. Russians and Ukrainians have watched it via the internet, and it has had a favourable rating on Russian film site Kinopoisk.

Mr Breus worked with many of the individuals portrayed and has given his verdict of the series.

Warning: This story contains plot details from the miniseries.

How much was fact and fiction?

"I was surprised they even brought us there," Mr Breus says of arriving at work the morning after the explosion. "The reactor looked so damaged, it seemed there was nothing else to do there."

Some of the events he witnessed that morning were realistically depicted in the show, he says, but others he describes as fiction.

"The Chernobyl catastrophe is depicted in a very powerful way, as a global catastrophe that absorbed huge numbers of people. Also, emotions and mood at that time are shown quite precisely, both among the personnel and the authorities.

OLEKSANDR KUPNYI

OLEKSANDR KUPNYI"However, the technological aspects have some discrepancies... which may not exactly [be] lies, but merely fiction," he adds.

What about the main characters?

The roles of three key personalities lie at the heart of the story: Plant director Viktor) Bryukhanov, chief engineer Nikolai Fomin and deputy chief engineer Anatoly Dyatlov. And Oleksiy Breus sees their portrayal as "not a fiction, but a blatant lie".

"Their characters are distorted and misrepresented, as if they were villains. They were nothing like that."

"Possibly, Anatoly Dyatlov became the main anti-hero in the show because that was how he was perceived by the power plant's workers, his subordinates and top-management, in the beginning. Later this perception changed."

All three men were sentenced to 10 years in a labour camp for their role in the disaster and series creator Craig Mazin maintains that Dyatlov in particular was a "real bully", who later made statements that were not credible.

Getty Images

Getty Images"The operators were afraid of him," Mr Breus agrees. "When he was present at the block, it created tension for everyone. But no matter how strict he was, he was still a high-level professional."

How accurate was portrayal of radiation?

Mr Breus says the series creators showed the radiation effects on the human body well.

In the hours after the explosion, he spoke to Oleksandr Akimov, the shift leader at the No. 4 reactor, and operator Leonid Toptunov, who both feature prominently in the series.

"They were not looking good, to put it mildly," he says. "It was clear they felt sick. They were very pale. Toptunov had literally turned white."

Within two weeks, both Mr Akimov and Mr Toptunov had died in a Moscow hospital of acute radiation syndrome (ARS).

"I saw other colleagues who worked that night. Their skin had a bright red colour. They later died in hospital in Moscow."

SKY UK LTD/HBO

SKY UK LTD/HBO"Radiation exposure, red skin, radiation burns and steam burns were what many people talked about but it was never shown like this. When I finished my shift, my skin was brown, as if I had a proper suntan all over my body. My body parts not covered by clothes - such as hands, face and neck - were red".

In the weeks immediately after the explosion, 29 power plant workers and firefighters died from ARS, caused by exposure to high doses of ionising radiation, according to Soviet officials.

Two more workers died because of injuries. The body of one of them, Valery Khodemchuk, was never recovered from the reactor debris.

How big was the fire?

Vasily Ignatenko, depicted in the series, was among the first firefighters sent to tackle the blaze.

Firefighters sent from neighbouring Pripyat did not know of any radiation exposure and Ignatenko died of acute radiation syndrome on 13 May 1986.

Arriving at work that morning, Mr Breus says he did not see any fire.

Getty Images

Getty Images"I saw the damage at reactor No. 4. You could see the equipment and pumps exposed. There was no smoke or fire, just fumes coming from the damaged part."

Most of the firefighters were pouring water on the damaged reactor, he says. "A thin stream the firemen poured probably evaporated before it even reached reactor."

Firefighters were also asked to help clear radioactive debris from the roof after the fire was extinguished.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHow accurate was portrayal of workers?

One of the most dramatic scenes in the miniseries shows three power plant workers volunteering to go into an underground tunnel beneath the damaged reactor to open a vital drainage valve.

There were fears that "lava" from the molten reactor could reach the water, triggering a further, potentially far more powerful explosion.

Contrary to reports that the three divers died of radiation sickness as a result of their action, all three survived.

Shift leader Borys Baranov died in 2005, while Valery Bespalov and Oleksiy Ananenko, both chief engineers of one of the reactor sections, are still alive and live in the capital, Kiev.

OLEKSIY ANANENKO/BBC/SKY UK LTD/HBO

OLEKSIY ANANENKO/BBC/SKY UK LTD/HBO"It was our job," says Oleksiy Ananenko, who was on shift at the time, while the others had been ordered in by their manager. They knew where the valves were, so they were the right men for the task.

"If I didn't do it, they could just fire me. How would I find another job after that?"

He points to a few inaccuracies in the TV portrayal.

Their faces were only partially covered by respirators, so they could speak to each other, they were not offered a reward, and they were not clapped on their successful return.

"It was just our work. Who would applaud that?"

SKY UK LTD/HBO

SKY UK LTD/HBOMiners were brought in to dig a tunnel under the reactor to create a space for a heat exchanger, to stop the molten core melting through the concrete pad and contaminating the groundwater, threatening millions of lives.

Temperatures beneath the reactor were high and the series shows them stripping naked.

"They took off their clothes, but not like it was shown in the film, not right down to nothing," Mr Breus insists, also pointing out that their role was ultimately not significant to the story.

The miners finished their work ahead of schedule, but by then the molten core had cooled itself.

"The miners are shown as tough guys who are not afraid of anything, but not the power plant workers."

How fatal was the 'Bridge of Death'?

In the series, Pripyat residents rush to a railway bridge for a better view of the fire, unaware of the exposure. Children are shown playing in the radioactive dust, which falls from the sky like snow.

This later became known as the "Bridge of Death" after reports that those who stood there allegedly died from radiation sickness.

But Mr Breus believes most Pripyat residents would have slept through the explosion, and he only learned of the accident when he arrived at work the following morning.

SKY UK LTD/HBO

SKY UK LTD/HBO"I've never heard there was a crowd of people who went to watch the fire at night," he says.

"In hospital, I was treated with a guy who biked to that bridge in the morning on 26 April to watch it. He got a mild type of acute radiation syndrome, a doctor said.

"Another friend treated at the same time said he had a date with his girlfriend close to the bridge that night. He had health problems afterwards."

How was the Soviet Union portrayed?

Oleksiy Breus says the accident helped reveal the substantial flaws of the Soviet system.

"For example, that useless secrecy, which became one of the reasons behind the Chernobyl disaster. When the operators pushed the red button, the reactor didn't stop but exploded."

But while many have complimented the show's attention to detail, he believes it is also one of the downsides of the TV series.

"There are many stereotypes shown, typical of Western portrayal of the Soviet Union," argues Oleksiy Breus. "A big cup, vodka, KGB everywhere."

Ultimately, though, he is happy the show has refocused attention on the disaster and the scale of damage caused.

"Its high rankings show that people are still interested in Chernobyl. It's not just a local interest, for a small group of people, but it is still worldwide."

UKRINFORM

UKRINFORM