Bannon plan for Europe-wide populist 'supergroup' sparks alarm

Getty Images

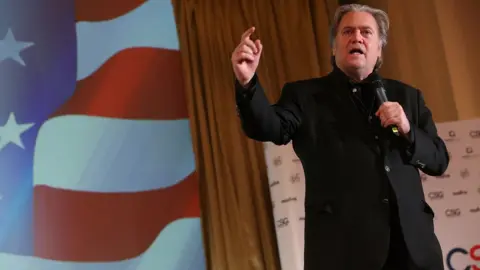

Getty ImagesPopulists and right-wingers have a grip on power in Italy, Hungary and Austria, and now Donald Trump's one-time adviser has designs on increasing their spread across Europe.

Steve Bannon dreams of a right-wing "supergroup" gaining a populist foothold in the European Parliament after next year's European elections.

But his plans have provoked a sharp response from across the political spectrum.

While one German minister attacked Steve Bannon's "hatred and lies", some populist figures in Europe were unimpressed with the idea of an American vowing publicly to unite them from a Brussels headquarters.

In the words of European studies specialist Alexander Clarkson, "most of these parties are set on anti-Americanism".

What's Bannon planning?

The former chief Trump strategist travelled to Europe after he was pushed out of the White House and then departed the right-wing Breitbart media empire. His ambition now is a populist implosion across the Continent.

Everything started with the Brexit vote in June 2016, he believes. It continued with the election of President Trump the following November and returned to Europe with the success of two populist parties in Italy's election last March.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesItaly is "in the vanguard of change in Europe", he argues, and along with Hungary's Viktor Orban is proof that the message from Europe's citizens is that people "want their countries back".

The next step, Mr Bannon has revealed, is for a non-profit foundation called The Movement to be set up in a Brussels office and recruit staff to help advise on messaging and targeting of data.

If it sounds reminiscent of Cambridge Analytica's use of data and Facebook to attract US voters, Mr Bannon was on the company's board of directors.

Raheem Kassam, a former aide to UKIP ex-leader Nigel Farage now signed up to the Bannon cause, calls the Brussels plan "a clearing house for the populist, nationalist movement in Europe", according to Reuters news agency. "We have started to staff up," he said, highlighting the issues of sovereignty, border control and jobs.

Why Bannon sees an opening

The first test is the May 2019 European Parliament vote.

The Movement would challenge the work of philanthropist George Soros, whose Open Society Foundations (OSF) have promoted liberal democracy across Europe for decades.

The difference would be that their organisation would be "on the side of ordinary people", says Mr Kassam.

There is already a template.

Hungary's self-styled proponent of "illiberal democracy", Mr Orban has already pushed the OSF out of Hungary and criminalised support for asylum seekers. He is someone Mr Bannon identifies as "Trump before Trump" as well as as "real patriot and a real hero".

In a speech in Budapest in May, Mr Bannon said Europe's "populist, nationalist revolt" was some 18 months to two years ahead of the US, because of the work of Mr Farage, Mr Orban and the leaders of Italy's ruling parties, The League and the Five Star Movement.

He has claimed credit for bringing the two Italian parties together a few days after the March vote.

In France too he has shared the stage with far-right leader Marine Le Pen, who reached the run-off in the 2017 presidential election only to be heavily defeated by Emmanuel Macron.

Getty Images

Getty Images"Let them call you racist, let them call you xenophobes, let them call you nativist. Wear it as a badge of honour," he said to her supporters.

While her party, renamed National Rally, has had to go cap in hand to Russian banks for funding, Mr Bannon believes he can attract funding that would have an impact on populist movements across the Continent, including the far-right Sweden Democrats and nationalist Finns party.

The Sweden Democrats are eyeing their best performance yet in September elections, with recent opinion polls suggesting their level of support is above 18%.

And it would not cost much. Brexit was built on a small sum while Italy's populists used their own credit cards, he says.

How is his message going down?

The reception so far has been hostile, or at best cool, for Mr Bannon's drive for populist unity.

Germany's centre-left Europe Minister Michael Roth said Europeans should not be afraid of "nationalist campaigns with which Mr Bannon would like to force Europe to its knees. Our values are stronger than his hate and lies".

There were warnings from other German parties too, with the pro-business FDP warning of a "frontal attack on the EU and European values".

Only Alice Weidel of the far-right AfD said Mr Bannon's ideas were "very exciting and ambitious".

Fellow leader Jörg Meuthen has been pretty damning, saying they have "basically no need of coaching from outside the EU".

Allow X content?

That is not to say he does not back a united populist right-wing front in Europe against immigration. In 2017, his party hosted a conference with Italy's League, Austria's Freedom Party, France's National Front and Dutch politician Geert Wilders.

A similar message has come from Austrian far-right MEP Harald Vilimsky, whose Freedom Party is already sharing power with Chancellor Sebastian Kurz's conservative People's Party.

"We will continue to work on this without any external influence," said Mr Vilimsky. While he did not rule out some form of co-operation, he said he could only judge if something concrete came from Mr Bannon.

Very little reaction has come from Italy or France, even though Ms Le Pen's partner Louis Aliot has visited Steve Bannon in London in recent weeks.

Mr Bannon did not appear to realise that most populist parties were profoundly anti-American, European studies lecturer Alexander Clarkson of King's College London told the BBC.

"If they embrace Trump, then all that anti-Americanism below the surface will turn itself against them, particularly in France," he said.

"That's why a lot of these parties are aware that getting into bed with Bannon is inherently risky."