Covid: Melbourne's hard-won success after a marathon lockdown

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMelbourne's grinding second coronavirus lockdown began in the chill of winter.

In early July, the nights were long and dark, and Australia's cultural capital was confronting the terrifying reality of another deadly wave of infections.

More than 110 days later, experts say it is emerging as a world leader in disease suppression alongside places including Singapore, Vietnam, South Korea, New Zealand and Hong Kong.

Raina McIntyre, a biosecurity professor at the University of New South Wales' Kirby Institute, told the BBC that Australia's response had been "light years ahead" of the US and the UK.

"It is just thoroughly shocking. When we think of pandemics we don't think that well-resourced, high-income countries are going to fall apart at the seams, but that is exactly what we have seen," she said.

At the end of Tuesday, Melbourne's five million residents will see an end to strict stay-home orders that put an entire city into a type of protective custody.

When the restrictions are lifted, Melburnians will have endured one of the world's longest and toughest lockdowns.

It's been controversial, calamitous for jobs and crushingly hard for many, but health specialists believe it has worked.

There is cautious optimism that with very low case numbers, the worst is over.

"I'm pretty proud of what we have achieved here," said Professor Sharon Lewin, director of the Doherty Institute in Melbourne. "The outcome has been extraordinary - not without its pain, though."

On Monday, Melbourne reported no new daily cases for the first time since June. In early August, it was recording more than 700 daily, and dozens of people were dying.

The Victorian state capital was at the heart of an unfolding public health crisis, and in other parts of Australia, which had mostly contained Covid-19, people held their breath.

"Europe and the US are facing enormously high numbers. In Victoria, we had an isolated outbreak pretty much just in Melbourne, and the rest of the country had extremely low, and in many states zero, numbers," Prof Lewin told the BBC.

"We had absolutely no choice but to go into a significant lockdown if we were going to rejoin the rest of the country, and that gave us motivation."

Face coverings became mandatory in Victoria, and a night-time curfew blanketed Melbourne.

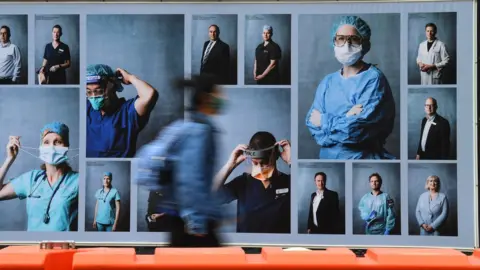

Life retreated indoors, while on the front-line of an invisible war, a growing number of casualties included health care workers and nursing home residents. The true impact on mental health may never be known.

More on Melbourne's lockdown:

"We understand why the government has taken that approach and it has worked, but we do feel that the government could move quicker to start easing the restrictions. They are taking an overly cautious approach," explained Adel Salman, vice-president of the Islamic Council of Victoria, last week.

"The strain on families, the rise in domestic violence - these are all concerning factors."

In a global pandemic, disease-control strategies vary from country to country. A key part in Australia's defences has been its geography. This is a large, isolated island. In March, it closed its international borders to foreign travellers to stop imported infections.

Almost 8.5 million tests have been carried out in Australia since the pandemic began. More than a third have been conducted in Victoria.

"We've done extraordinarily well on testing," Prof Lewin told the BBC.

"The capacity to [do] follow-up tests and isolate became harder as the numbers peaked in Melbourne, but we have really good systems now in place and that has been a secret to the successful outcome."

Another expert, Michael Toole, wrote in The Conversation: "Only Vietnam and Hong Kong have enjoyed comparable success in quashing the second wave.

EPA

EPA"Victorians' sacrifice during lockdown has left Australia well placed to sustain very low numbers of cases through the coming summer," said Prof Toole, an international health specialist at Melbourne's Burnet Institute.

But serious mistakes have been made.

Citizens and permanent residents are allowed to return to Australia and on arrival they face 14 days in mandatory quarantine.

But security breaches at hotels in Melbourne allowed the virus to pass from passengers to staff, and into the community, igniting a deadly second wave. These failures are being examined by a judicial inquiry.

There were criticisms, too, that Victoria's health service was under-resourced when the crisis hit, and that in the early stages contact tracing of known infections was inadequate.

Federal Health Minister Greg Hunt said Victoria "had real challenges but it is improving".

He has identified four critical pillars in Australia's determined response to Covid-19: the closure of its international borders, "uniformly good" testing in all states and territories, contact tracing, where New South Wales has set "the gold standard", and a compliant community that has embraced distancing protocols.

EPA

EPAVictorian Premier Daniel Andrews has said the state is ready to take "steady steps towards that Covid-normal summer [and] a Covid-normal Christmas".

But there is no premature sense of triumph. More than 900 Covid-19 related deaths have been reported in Australia, the virus has not been eliminated and vigilance will need to trump apathy and complacency.

"We can't manage to contain the disease unless we change the way we live until we can have enough vaccines that are effective enough for everyone," warned Prof McIntyre.

"We can't just go into denial and wish our lives were back to normal. It's a once in-a-lifetime natural disaster of catastrophic proportions."