What a breakfast murder in India says about attitudes to wife beating

Tasveer Hasan

Tasveer HasanLast month, police in India arrested a 46-year-old man who allegedly murdered his wife because his breakfast had too much salt.

"Nikesh Ghag, a bank clerk in Thane, near the western city of Mumbai, strangled his 40-year-old wife in a fit of rage because the sabudana [tapioca pearls or sago] khichdi she served was very salty," police official Milind Desai told the BBC.

The couple's 12-year-old son, who witnessed the crime, told the police that his father followed his mother, Nirmala, into the bedroom complaining about salt and started beating her.

"He kept crying and begging his father to stop," Mr Desai said, "but the accused kept hitting his wife and strangled her with a rope."

After Mr Ghag stormed out of the house, the child called his maternal grandmother and uncle.

"By the time we reached the scene, her family had rushed her to hospital, but by then she was already dead," Mr Desai said.

The accused later surrendered at the police station, where he told officers that he suffers from high blood pressure. He was sent to jail.

Nirmala's family told the police that Mr Ghag had been quarrelling with her over "domestic issues" for the past 15 days. Mr Desai said they had not received any complaint about this from the victim or her family.

The murder of a woman by her husband, triggered by a quarrel over food, routinely makes headlines in India.

Take some recent cases:

- In January, a man was arrested in Noida, a suburb of the capital Delhi, for allegedly murdering his wife for refusing to serve him dinner.

- In June 2021, a man was arrested in Uttar Pradesh after he allegedly killed his wife for not serving salad with his meal.

- Four months later, a man in Bangalore allegedly beat his wife to death for not cooking fried chicken properly.

- In 2017, BBC reported on a case where a 60-year-old man had fatally shot his wife for serving his dinner late.

Gender activist Madhavi Kuckreja says "death brings attention" but these are all cases of gender-based violence which is "invisibilised".

Mostly reported under the legal term of "cruelty by husband or his relatives", domestic violence has consistently been the most reported violent crime against women in India year after year. In 2020 - the last year for which crime data is available - police received complaints from 112,292 women - which breaks down to about one every five minutes.

Such violence is not unique to India. According to the World Health Organization, one in three women globally face gender-based violence, most of it inflicted by intimate partners. The numbers for India are similar.

Activists here have to battle with the culture of silence that surrounds it and - shockingly - an overwhelming approval for such violence.

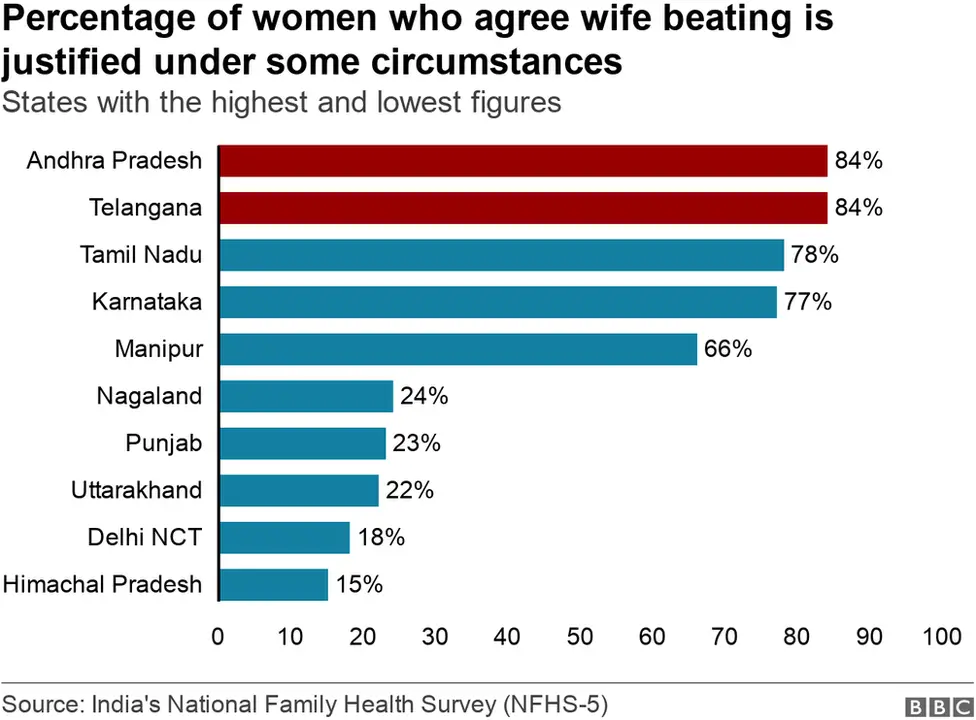

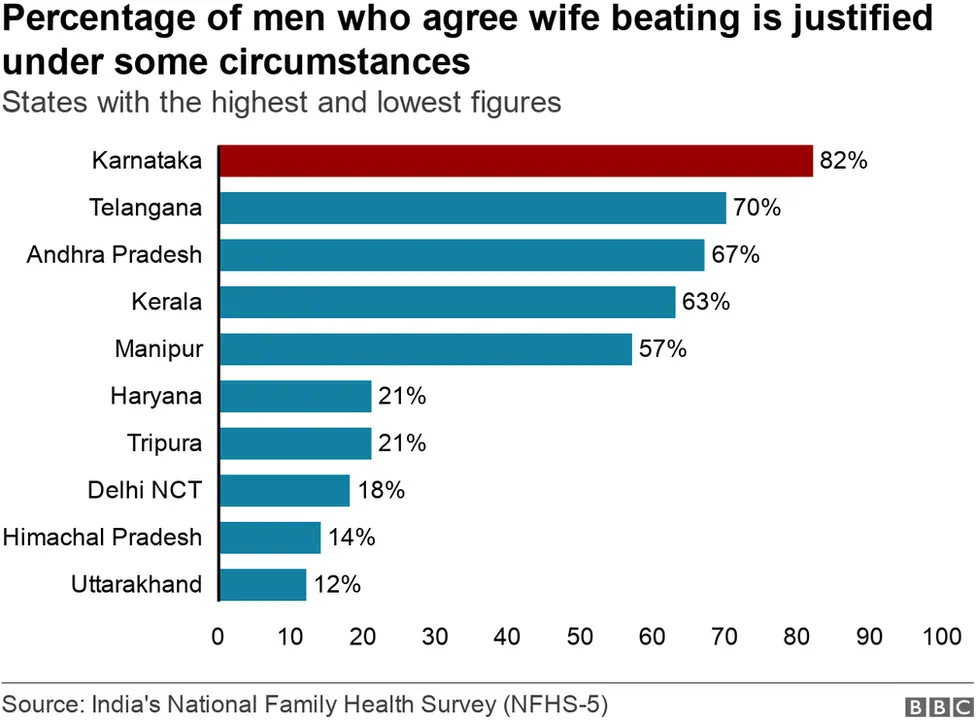

The latest figures from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS5), the most comprehensive household survey on Indian society by the government, are revelatory.

More than 40% of women and 38% of men told government surveyors that it was ok for a man to beat his wife if she disrespected her in-laws, neglected her home or children, went out without telling him, refused sex or didn't cook properly. In four states, more than 77% women justified wife beating.

In most states more women than men justified wife beating and in every single state - the only exception being Karnataka - more women than men thought it was okay for a man to beat his wife if she didn't cook properly.

The numbers have gone down from the previous survey five years ago - when 52% women and 42% men justified wife beating - but the attitudes haven't changed, says Amita Pitre, who leads Oxfam India's gender justice programme.

"Violence against women - and its justification - is rooted in patriarchy. There's high acceptance for gender-based violence because in India, women are considered the subordinate gender," she told the BBC.

"There are fixed social notions about how a woman should behave: she should always be subordinate to the man, always defer in decision-making, should serve him and she must earn less than him, among many other things. And the acceptance for the reverse is very low. So, if a woman challenges it, then it's all right for the husband to show her 'her place'."

The reason why more women justify wife beating, she says, is because "patriarchy reinforces gender norms and women imbibe the same ideas, their beliefs get moulded by the family and society".

Ms Kuckreja, who set up Vanangana, a charity that has been working with battered women for a quarter of a century in in northern India's Bundelkhand - one of the poorest regions in the country - says a popular piece of advice given to new brides translates to "you are entering your marital home in a palanquin, you must only leave on your funeral bier".

So most women, even those who are beaten regularly, accept violence as their fate and do not report it.

"Even though there's more reporting in the past decade, wife beating is still hugely underreported in India. Such cases are hard to report and record. Most people would still say that 'what happens at home must remain at home'. So, women are discouraged from going to police," Ms Kuckreja says.

Also, they have nowhere to go if they leave their marital home, she says.

"Parents often don't want them because of stigma and, in many cases, because they are poor and unable to feed additional mouths. There is no support system, few shelter homes and the compensation awarded to abandoned women is a pittance - often in the range of 500 to 1500 rupees, which is not enough for a woman to survive, leave alone feed her children."

Pushpa Sharma, who heads Vanangana, told me about two cases she received last month where women were beaten and then abandoned by their husbands, along with small children.

"In both cases, their husbands dragged them out of their homes by their hair and assaulted them in front of the neighbours. They claimed that they weren't cooking properly, but that is always part of a litany of complaints. The meal is just a trigger point."

A woman, she says, can be "beaten for giving birth to daughters and not a 'male heir', or because she's dark-skinned or not pretty, or she didn't bring enough dowry, or the husband was drunk, or she didn't serve food or water quickly enough when he returned home, or she put more salt in the food, or forgot to add it".

Tasveer Hasan

Tasveer HasanIn 1997, Vanangana launched a street play called Mujhe Jawab Do [Answer Me] to sensitise people about domestic violence.

"It started with the line, 'Oh there is no salt in daal… (lentil soup)'," Ms Kuckreja says.

"After 25 years of our campaign, little has changed. And that's because of the premium we place on marriage. We do everything to save a marriage - it's sacrosanct, it must last forever.

"That thought needs to change. We must empower women. They don't need to put up with beating," she says.

Data interpretation and graphics by BBC's Shadab Nazmi

For information and support on domestic abuse, contact:

- Police helpline: 1091/ 1291

- The National Commission for Women’s WhatsApp helpline: 72177-35372

- Helpline for Shakti Shalini, a Delhi-based NGO: 10920

- Crisis helpline for Sneha, a Mumbai-based NGO: 98330-52684 / 91675-35765