Coronavirus: Five ways virus upheaval is hitting women in Asia

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSince its outbreak in China, the coronavirus has killed or infected tens of thousands of people across Asia, and is spreading worldwide.

As well as the health battle, the social impact of the virus is significant and across Asia, it is women who are being disproportionately affected.

"Crisis always exacerbates gender inequality," says Maria Holtsberg, humanitarian and disaster risk advisor at UN Women Asia and Pacific.

Here are five ways that women in Asia are bearing the brunt of the upheaval.

1. School closures

"I have been at home for over three weeks now with the kids," says journalist and mother-of-two Sung So-young.

She lives in South Korea, which recently announced it was postponing the start of the new school year by an additional two weeks, so children won't return to class until 23 March.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs of 4 March, just more than 253 million children in South Korea, China and Japan who would normally attend pre-primary to upper-secondary classes were not attending school, according to Unesco's latest figures.

This measure has been especially difficult for people like Ms Sung, as in many East Asian countries mothers shoulder a disproportionate burden at home, and she says she has been feeling "depressed".

"To be honest, I want to go into the office because I can't really focus at home," says Ms Sung. "But my husband is the breadwinner and he can't really ask for time off."

Ms Sung, her 11-year-old daughter and five-year-old son spend their days playing games and watching films. She tries to get some work done when they're asleep.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHer situation is reflective of South Korea's poor record on gender equality at work. In 2020, the World Economic Forum ranked it 127 out of 155 nations for women's economic participation.

Ms Sung has anecdotally heard of some companies cutting the wages of female employees who can't come into the office due to childcare following school closures.

"Many companies don't say this but they still see working mothers as a burden, with a less competitive spirit. After all if you didn't have children you could come into the office more," she says.

Japan's government announced this week it will pay businesses up to $80 per person per day if their employees take paid leave to take care of their children due to school closures.

Day care centres and after-school clubs are exempt from the closure policy to help parents, but this has also prompted questions about the effectiveness of the shutdowns.

"Having schools closed does not help stop the virus entirely from spreading. It only increases burdens of working mothers," says Natsuko Fujimaki Takeuchi who is small business owner.

"It's especially challenging for my business, I don't get the same support as bigger companies do for economic damage."

2. Domestic violence

With millions of people in China spending time indoors, rights activists say there have been increasing instances of domestic violence.

Guo Jing, a female activist who had only moved to Wuhan - the origin of the virus - in November 2019, says she has personally received enquiries from young people living in the quarantined city about witnessing domestic violence between their parents. She said the callers had no idea where to turn to for help.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesXiao Li, a Chinese activist living in Henan province wrote on Chinese social media of her concern after a distant relative was assaulted by her ex-husband and made a plea for help.

"Initially we found it impossible to get a permit to allow her to leave her village," Ms Li told the BBC.

"Eventually after much persuasion, the police finally allowed an exit and entry permit to be granted so my brother could drive and meet her and the children."

As these individual reports of domestic violence surface on social media, some women have created posters reminding people to counteract domestic violence when they see it and not be passive bystanders.

The hashtag #AntiDomesticViolenceDuringEpidemic #疫期反家暴# has been discussed more than 3,000 times on the Chinese social media platform Sina Weibo.

Last week, Feng Yuan, the director of Beijing-based women's rights nonprofit Weiping, said her organisation had received three times as many inquiries from victims than they did before quarantines were in place.

"The police should not use the excuse of the epidemic for not taking domestic violence seriously," she says.

UN Women are also concerned about the possible diversion of resources with increased efforts to contain outbreaks.

"Diverting resources from critical services that women rely on, such as routine health checks or gender based violence services, is something we are very concerned about," says Ms Holtsberg.

3. Frontline care workers

Women form 70% of workers in the health and social sector, according to the World Health Organisation.

Chinese media has been promoting stories praising the "saintliness" and "warrior-like" nature of women working on the frontline as nurses. But what is the reality for these female medical staff?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA video showing female medical workers from Gansu province collectively having their heads shaved before being despatched to help fight the coronavirus outbreak gathered traction online this month. The story of a nine-month pregnant medical worker who had recently suffered a miscarriage but went back to work also sparked a huge backlash for being a show of propaganda and setting a dangerous precedent.

Last month, the BBC spoke to one nurse who said hospital staff were not allowed to eat, rest or use the toilet during their 10-hour shifts.

While that applies to all hospital staff, women also shoulder another layer of discrimination.

Jiang Jinjing, the woman behind the Coronavirus Sister Support campaign, which is trying to deliver feminine hygiene products to front line workers in Hubei province, recently told online media publication Sixth Tone that women's menstruation needs are being overlooked.

Writing on her Weibo page, she said: "As of 28 February, 481,377 period pants, 303,939 disposable pants and 86,400 pads have been donated."

Jiang Jinjing says not many people thought of providing the right period products for the tens of thousands of female medical workers.

After the volunteers' campaign was applauded by many on Chinese social media, the state-run China's Women's Development Foundation said it would send menstrual products to female medical workers.

What do I need to know about the coronavirus?

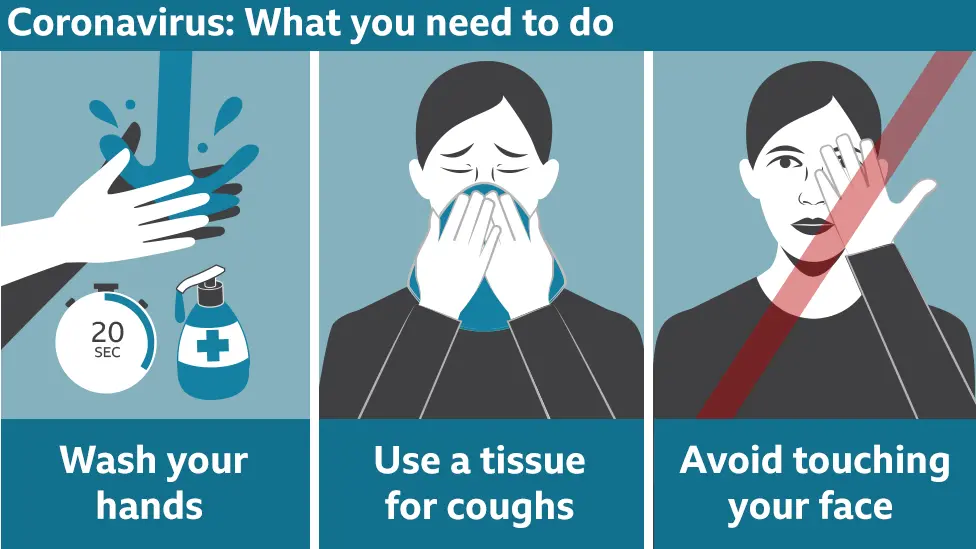

- EASY STEPS: What can I do?

- A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

- GETTING READY: How prepared is the UK?

- MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

- VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

4. Migrant domestic helpers

An estimated 400,000 women work as domestic staff in Hong Kong, most of them coming from the Philippines and Indonesia. These women are growing increasingly anxious about not only their precarious work status, but also their ability to find protective items such as face masks and hand sanitisers.

Getty Images

Getty Images"The panic buying of masks has driven prices so high that they are no longer affordable for migrant workers," says Cynthia Abdon-Tellez, general manager for the charity Mission for Migrant workers in Hong Kong.

"Not all migrant workers get masks from their employers, we have to buy them on our own expenses and it's very expensive. Some, who get masks from their employers, will use the same mask for a week," one Indonesian migrant worker in HK, Eka Septi Susanti told BBC Indonesia.

Ms Abdon-Tellez says her organisation has started collecting masks to distribute to migrant workers, where employers aren't providing them.

"The Indonesian consulate distributed free masks but it's not enough - it took an hour [to wait in line] to get three masks. We need at least six masks for a week," says Sring Sringatin, the chairperson of the Migrant Workers Association in HK.

Advice from the Hong Kong government has also resulted in frustration among foreign domestic workers in the city. The government urged them to stay indoors on their one day off a week, in order to safeguard their health and reduce the risk of contamination.

This removes precious social time from women living far away from their own families and loved ones, and puts them at risk of exploitation.

KJRI Hong Kong

KJRI Hong Kong"Migrant workers who stay home on off days because they can't go out are still working," says Ms Sringatin.

"They will cook for their employers, babysit or care for the employers' parents, without compensation. Those who insisted on taking a day off were threatened with being dismissed."

It's not just the women themselves that are impacted. Millions of people rely on their income that they send home to the Philippines and Indonesia.

Personal remittances from overseas Filipino workers reached a record high of $33.5bn (£25.7bn) in 2019.

ING Bank Manila senior economist Nicholas Mapa says remittances from Filipino workers overseas account for roughly 9% of GDP, and the effect of the virus will likely be felt by the Philippine economy.

"With consumers staying indoors, limiting demand for various services industries where Filipinos are generally employed, it is hurting their chances to send home funds. Travel restrictions and mobility are also affected , threatening pay checks and even job security," he told the BBC.

5. Longer term economic impact

Economists and governments are discussing predictions that the global economy could grow at its slowest rate since 2009 because of the outbreak.

Getty Images

Getty Images"Overall, the coronavirus has an immense impact on travel, production and consumption, which has an impact on many sectors and thus women and men alike," says Christina Maags, a lecturer at SOAS University of London.

"However, low income women are particularly affected by the slowdown in consumption as they tend to be employed in hospitality, retail or other service industries."

In China, "since many migrant women do not have employment contracts, the coronavirus has meant that they do not receive any income - if they do not work, they do not get paid", she says.

"With no social security to fall back on, they face the dilemma of either returning to work and potentially getting sick or needing to pay for other forms of accommodation. Alternatively, they might be forced to stay at home and live off the little savings they have. This puts them in a very difficult situation".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd some South East Asian garment factories, which rely on raw materials from China, are being forced to close.

According to the government in Myanmar, more than 10 factories have closed since January, though the labour ministry said not all were linked to the coronavirus.

Ma Chit Su told BBC Burmese that her family had depended on her wages from her now-closed garment factory job.

"I don't care about compensation, I just want my job back at the factory," she says.

From UN Women's perspective these are the some of the women who will suffer the biggest impact, including daily wage earners, small business owners and those working in informal sectors.

"The differential needs of women and men in long-and-medium-term recovery efforts also need to be considered," says Mohammad Naciri, regional director of UN Women Asia and the Pacific.

"Women are playing an indispensable role in the fight against the outbreak - as health care workers, as scientists and researchers, as social mobilisers, as community peace builders and connectors, and as caregivers.

"It is essential to ensure that women's voices are heard and recognised."