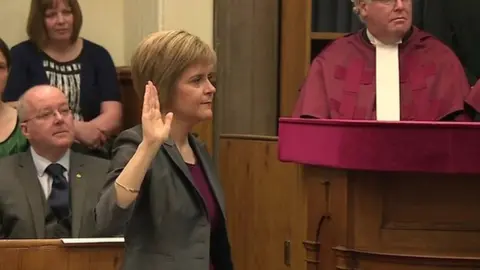

Assessing Nicola Sturgeon's record 2,743 days at the top

PA Media

PA MediaNicola Sturgeon has become Scotland's longest-serving first minister. So what has she done with her seven-and-a-half years at the top of Scottish politics - and what could be next for the SNP leader?

It is fair to say that even now, after 23 years in parliament and a record-breaking tenure in Bute House, Nicola Sturgeon is still at the peak of her powers.

She is the face and focal point of Scottish politics. Say "Nicola" to anyone in the country, and they will immediately know who you mean.

She has utter command over her party, the SNP, which in turn cruises through every election it contests. She is on her third prime minister and has seen off half a dozen opposition party leaders.

Election winner

Last year she went toe to toe with her predecessor and mentor, Alex Salmond, in a bitter public row - and not only won out, but demolished his new party at the ballot box.

This commanding political position - and indeed the fact her tenure literally started with a stadium tour - may contrast somewhat with the rather private woman who famously enjoys nothing more than curling up with a book in her spare time.

But after 2,743 days in office, a global pandemic, Brexit and everything else, perhaps she has become so synonymous with the role of first minister that she can't just switch it off for a long weekend.

How to evaluate Ms Sturgeon's time in charge? Just putting numbers to it hardly scratches the surface.

She has guided the SNP to thumping wins in three general elections, two Holyrood ballots, two council contests and even a post-Brexit European Parliament poll.

The party was already in a strong position - she started off with an unprecedented Holyrood majority, won by Mr Salmond - but under Ms Sturgeon it has become a juggernaut.

What has the first minister done, then, with all of her electoral success and the many mandates given to her party?

There have been some notable wins. Last year, the government completed delivery of a policy set out in Ms Sturgeon's very first speech as SNP leader in 2014, to double the allowance of free childcare.

This goes hand in hand with other family-friendly achievements like the Baby Box and the expansion of free school meals.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere has been a distinct social justice focus, with a new welfare agency - Social Security Scotland - set up and in the process of taking on benefits old and new, like the Scottish Child Payment.

And in recent years there has been a green tinge to policies, with Ms Sturgeon declaring a climate emergency before throwing herself into the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow.

However, there have also been areas where her government has fallen short of the goals she set for it herself.

In 2016, she said that it was her "personal defining mission" and the government's "number one priority" to close the poverty-related attainment gap in schools.

The government's aim was to "substantially eliminate" the gap over the course of a decade, but last week the education secretary said such targets were "arbitrary" and that this had "always been a long-term project".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEducation seems caught up in a near-constant cycle of reform, with the funding model for schools in deprived areas being reviewed at the same time as Education Scotland and the exams body are replaced.

The government has also wrestled with issues like the record level of drug-related deaths, and has been criticised for having a tangle of industrial strategies.

The lists of successes and failures are as long as each of your arms. Ministers succeeded in setting up a national investment bank, but gave up on plans for a state-run energy company.

Hits and misses

The Queensferry Crossing was delivered under budget, but costs and timescales in ferry construction projects have ballooned. Minimum unit pricing of alcohol survived a succession of legal challenges, while the named person scheme did not.

After this long in power, any government will have accrued its share of hits and misses. The challenge is to keep coming up with new ideas to keep the momentum going.

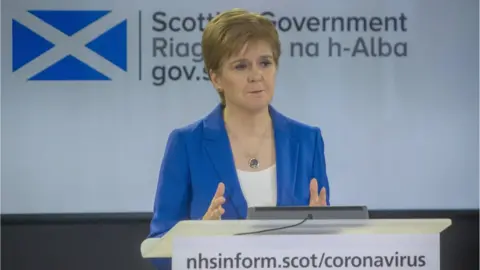

PA Media

PA MediaSome of the government's plans for reforms ran into the same brick wall as the rest of society in March 2020.

The pandemic was, in a way, the moment devolution truly came of age - with the governments in London, Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast feeling their way through the crisis distinctly, but also together.

Nobody who watched Ms Sturgeon's near-daily briefings during the early stages of the pandemic could have been in any doubt that she was in charge. Even UK ministers saw her communication skills as an asset.

That said, the differences between the nations in the end largely boiled down to timing. The administrations imposed and lifted largely the same measures - and indeed made the same mistakes, such as the discharge of untested hospital patients into care homes.

Ms Sturgeon has highlighted that as a regret, saying that some pandemic decisions will live with her for the rest of her days - although it will be down to a public inquiry to decide whether they were the right ones.

It cannot be doubted that the briefings increased Ms Sturgeon's profile. It could also be argued that the pandemic also stiffened her dedication to public service. She had always been meticulous about detail and preparation, but the pandemic necessarily elevated that to a new level.

The first minister rarely delegated so much as a television appearance to her ministers, almost visibly carrying the burden of many big decisions alone - even the one where she had to sack her chief medical officer.

So it feels slightly ironic that Ms Sturgeon is spending this milestone moment in isolation, having tested positive for the virus.

And while she says she is working from home, it is also arguable that this is the closest thing she has had to a holiday for over two years.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDid the ascent of Scotland's first female first minister break the glass ceiling of Scottish politics?

Ms Sturgeon swiftly appointed a female chief of staff, set up the UK's first gender-balanced cabinet and passed legislation setting targets for women's representation on public authority boards.

For a period on either side of her first Holyrood election win, all three major parties were led by women, with Labour's Kezia Dugdale and Tory Ruth Davidson part of a broader move towards more equal representation at Holyrood.

More than half of the SNP's MSPs are now women - up from 25% when the party first entered government in 2007 - and Ms Sturgeon has made a point of speaking out about women's issues like the menopause.

Right now, though, the first minister finds herself at odds with some women's groups about plans to reform the Gender Recognition Act (GRA).

Her government was also rocked by its mishandling of harassment complaints against Alex Salmond, with Ms Sturgeon repeatedly apologising for how the women involved were let down.

After the torturous inquiries, it is fair to question whether women in government feel safer and more supported to make complaints against powerful men than they did before the #MeToo movement began.

And we clearly do not live in a brand new world where politics is free from misogyny. Even at the point where the Scottish and UK governments were both led by women, a newspaper chose to write headlines about their legs rather than their policies.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNow we come to the question of what Nicola Sturgeon does next, fresh off the back of another election win.

There are some ongoing projects - like gender reforms, plans for a National Care Service and ScotRail's move into public ownership - and an injection of fresh ideas as part of the SNP's Holyrood pact with the Greens.

The big thing missing from her record though is an independence referendum, which seems to have been scheduled for "next year" at least since Brexit reignited the issue in 2016.

Ms Sturgeon remains adamant that a poll will be held in 2023, but it is fair to say there is scepticism about this even within her own party.

This is chiefly because the matter is not entirely up to MSPs or the Scottish government, with Ms Sturgeon determined to seal an agreement with UK ministers first. She wants to actually deliver independence, so only an internationally recognised, gold-standard contest which both sides engage with whole-heartedly will do.

For all the talk of potential legal battles, this remains a political problem. And Boris Johnson, for all the SNP may adore him as a recruiting sergeant for their cause, is also an intractable blockage.

The prime minister has his own problems to deal with right now, and the chances of him - or, should he be ousted, his successor - signing up to a referendum any time soon appear vanishingly slim.

So with that in mind, could Ms Sturgeon conclude that she has done her bit?

With the independence movement at a crossroads, will it be up to the next leader to decide how to move forward?

After all, her place in the history books is already assured. The first female first minister as well as longest-serving, a pandemic leader and architect of a new generation of devolved benefits and public services.

But with Ms Sturgeon in as comfortable and powerful a position as she has ever occupied at the top of Scottish politics, few would bet against her making at least one more push to achieve the core ambition that has driven her all these years.