What's it like to live with a mechanical heart pump?

Greg Funnell/ British Heart Foundation

Greg Funnell/ British Heart FoundationFifty years ago, renowned surgeon Christiaan Barnard carried out the world's first heart transplant, a technique that today has become routine.

Up to 300 people are currently on the UK's transplant list and many are fitted with mechanical pumps as a "bridge" to getting a new heart.

Called left ventricular assist devices (LVADs), they help circulate blood around the body.

But many spend years relying on the battery-powered pump while their wait for a transplant continues. So what is life like for these people?

Jim Lynskey, a 22-year-old university student, was fitted with an LVAD in 2015, aged just 19. He is believed to be the youngest person in the country to have one.

A week after his birth, Jim and his twin sister Grace contracted meningitis. She fought off the virus, but her brother was left with a badly damaged heart.

Mr Lynskey, like most LVAD patients, is on the non-urgent transplant list.

"I've never been offered a heart," he said.

"It's something very unusual considering that there are not too many other 'competitors' on the transplant list who are my height and weight at such a young age."

Greg Funnell/ British Heart Foundation

Greg Funnell/ British Heart FoundationThe Sheffield Hallam undergraduate lives an independent lifestyle away from home at university.

Wires come from his body to a power pack, which he must keep with him at all times.

Conscious of how it looks, the student keeps the batteries in his pockets and the computer attached to his belt, so it is all out of sight.

He dreams of joining in with activities like swimming and exercising with his friends without worrying.

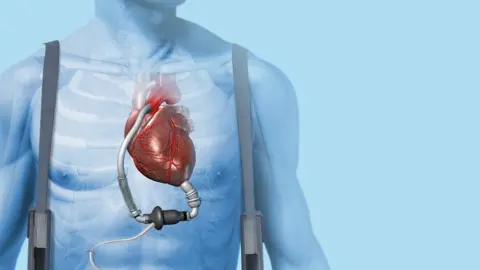

What is a left ventricular assist device?

Science Photo Library

Science Photo Library- An LVAD is a kind of artificial heart pump

- It is used to treat people with severe heart failure and is sometimes given to people on the waiting list for a heart transplant

- Normally the left ventricle, one of the human heart's four chambers, pumps blood into the aorta and around the body

- In the event of severe heart failure, the heart is too weak to do this

- So the device helps the failing organ and aims to restore normal blood flow

- Some patients awaiting a heart transplant may need an LVAD if they are unlikely to survive until a suitable donor organ becomes available

Source: British Heart Foundation

At night, the machine's whirring often keeps him awake.

When he does sleep, Mr Lynskey's batteries charge in a docking station. This gives him eight to 10 hours' power the following day.

"Showering is very difficult because I can't get the wound too wet," he said.

"It's tricky to keep up with the uni lifestyle. Maybe a drink gets spilt on you in a club and you have to dash home. Any sort of knock or liquid spilling on it is terrifying.

"It's difficult to live with something so abnormal, especially surrounded by such a young, best-years-of-your-life environment."

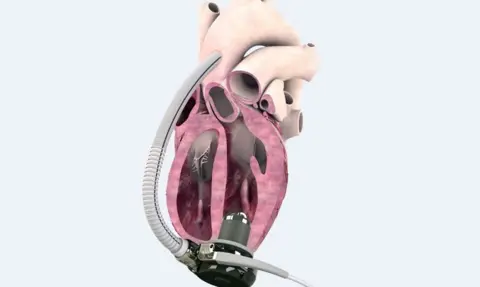

Calon Cardio

Calon CardioWeighing only seven stone (44kg) when fitted with the device three years ago, Mr Lynskey, from Warwickshire, has now gained weight.

"I feel so much better than I did before I had the pump. My body functions have become more routine.

"But the difficulties are pretty overwhelming at times."

In October, Mr Lynskey's heart pump failed and he had to have a newer LVAD fitted in hospital. He spent his 22nd birthday in a coma.

"[Grace and I] are really close. She was pretty devastated. We've been for a [birthday] meal since."

'Many limitations'

Miss Lynskey, who recently graduated from Birmingham City University, was in her first year when her twin brother got his heart pump.

"It's difficult for her. I would argue it's been harder for her than me," her brother said.

The student describes himself as a positive person and has set up a campaign called Save9Lives to raise awareness about organ donation.

While he is grateful for the pump, which has helped keep him alive, he said a transplant would eliminate "so much fear and so many limitations" and hopes to one day turn his campaign into a registered charity.

Mr Lynskey, originally from Redditch, Worcestershire, is not alone.

Others have turned to the internet to share their stories and encourage wider awareness of organ donation.

More than 6,500 people are members of online community, My LVAD.

Recipients, relatives and medics share their stories and offer encouragement and advice.

Discussions range from dealing with the stress and financial worry of ill health to what kind of shirts are easiest to wear with an LVAD and wire.

One recipient tells the online community his pump is "truly life-saving technology but has its limits".

Current pumps have their drawbacks. As well as the restrictions of protruding wires and carrying batteries, patients can suffer complications including infections and bleeding.

And for some people, including those deemed too ill for a heart transplant, LVADs are permanent - a so-called destination therapy.

PA

PAPeter Houghton was one such person.

Before his death in 2007, he entered the Guinness World Records as the longest surviving artificial heart transplant patient.

The psychologist, from Birmingham, was fitted with a Jarvik heart pump in June 2000.

He was living a busy, caring life counselling terminally-ill people, when his heart began to fail.

By the time he walked into the office of heart surgeon Stephen Westaby some years later, he was breathless, ridden with sores and gout and felt it "was too painful to live".

Prof Westaby offered Mr Houghton, who he said was deemed too ill for a transplant and had only weeks to live, the radical heart pump treatment.

He recounts in his heart surgery memoir Fragile Lives that despite the risks, Mr Houghton seized the chance as his "lottery win".

After the operation, Mr Houghton had to carry a bag containing the pump's controller and batteries. An external wire from a metal plug in his skull carried power to the heart device.

Artificial Heart Fund

Artificial Heart Fund He went on to become an ambassador for LVADs, completed a 91-mile charity canal walk and attended conferences around the world.

John Lloyd, his neighbour in Edgbaston, described his friend as "inspirational" and chaperoned him on a four-week US tour to heart centres and pump-makers, where the psychologist was "treated like a bit of a celebrity".

"He wanted to tell people that there was an alternative to transplant," he said. "And to show people how well he was and that he could live a full and active life with a mechanical device implanted into his body."

PA

PAMr Houghton, who fostered more than 10 children with his wife Diane, called the seven further years the pump gave him his "extra life" and he raised cash and awareness for research, becoming chairman of the Artificial Heart Fund charity.

But his main goal had been for the pumps to become a "destination therapy" - an alternative to transplant, Mr Lloyd added.

Prof Westaby said Mr Houghton became a "great friend" and encouraged him to develop a more affordable pump for use in Britain.

The retired surgeon is now part of a team in Swansea creating the Calon Cardio MiniVAD, the first British pump. The team hopes to raise £40m to begin clinical trials next year.

The professor believes Mr Houghton's legacy demonstrates "the enormous potential" of mechanical pumps to help thousands of patients who have severe heart failure, ineligible for transplant.

The United States and other countries have adopted miniaturised rotary blood pumps as an alternative to transplant for some patients with advanced heart failure, he said.

Dr Yoshifumi Naka, a cardiac surgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, said LVADs were bringing about a "paradigm shift" in the treatment of end stage heart failure.

In the past two years the US hospital has doubled the number of devices it implanted while "all over the country, as well as all over the world, the implantation of LVADs is growing rapidly," he said.

Analysis: Dr Steve Shaw, consultant cardiologist in Manchester

The survival of patients on ventricular assist devices has been gradually improving since their inception more than 50 years ago.

It is now typical for patients to live for several years with a good quality of life. Subsequently, there is a desire to extend the treatment to a wider group of patients who are transplant ineligible (typically due to higher age, or the presence of other medical problems).

Survival for these Destination Therapy (DT) patients is less than a bridge to transplant and complication rates are also higher.

There is uncertainty among commissioners over whether DT represents a value-for-money intervention within the cost constraints of our NHS.

Inevitably however, technology will continue to advance and my opinion is that these devices will undoubtedly become a genuine alternative to transplant in the future.

For Jim Lynskey, a transplanted heart would give him a "better quality of life". But he will not be on the register for at least the next six months.

The surgery to fit the latest LVAD means his body must be given time to recover properly.

"In truth, I would be delighted to stay away from the surgical table for 10 years with this pump and then perhaps consider transplant," he said.

"If the call did come for a heart transplant one day before then, I would be unlikely to turn down the opportunity."