Were police too quick to believe historical sex abuse claims?

BBC

BBCCarl Beech - the paedophile whose false claims of abuse against public figures were once described as "credible and true" by police - has been sentenced to 18 years for perverting the course of justice. In the aftermath of the Jimmy Savile scandal, were police too quick to believe historical sex abuse allegations?

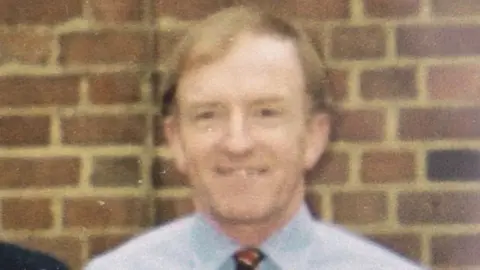

Simon Warr was a teacher at boarding schools in Suffolk for most of his career, taking language classes and rugby with older pupils.

He was 59 when his life changed, with a bang on the door one day at 07:15.

"Four police officers swept past me, pushing me on to the cabinets, and the fifth one read me my rights," he tells the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme.

A former pupil had alleged he had been touched inappropriately after a PE lesson 30 years earlier.

"I said to the police, 'I don't teach PE, I don't teach 12-year-olds games'," he says, "but they just wouldn't listen."

'Not properly investigated'

His arrest took place in 2012, just months after the Jimmy Savile scandal.

Since then, 6,617 suspects have been identified by detectives investigating historical child abuse allegations.

Operation Hydrant was set up in 2014 to oversee claims of "non-recent" abuse in institutions or by people of public prominence.

Some 7,396 possible crimes on its database have now had a final outcome. Of those 2,043 - or 29% - ended in a conviction.

But faced with a huge increase in allegations, critics say police and prosecutors were often too quick to believe victims' accounts before they could be properly investigated.

In Mr Warr's case, details of his arrest were broadcast on the BBC that evening.

His diary, photos, computer and phone were confiscated and, he says, used by officers to contact "numerous" former pupils.

"The police tried desperately for others to come forward.

"When they went to see former pupils... it was made quite clear I was going to be prosecuted and they were looking for people strong enough to say I'd done similar things to them.

"They had no intention of getting to the bottom of what happened. It certainly turns the whole edict of 'innocent until proven guilty' on its head."

Improving victims' rights

In the past it had been very difficult for victims of historical abuse to get any form of justice.

A series of changes was brought in to improve that.

From 1988, those accused lost an automatic right to anonymity.

A crucial ruling in 1990 meant separate allegations no longer needed to be "strikingly similar" to be considered together at trial.

In 2014, Her Majesty's Inspector of Constabulary (HMIC) issued guidance which said, when a crime is recorded, "the presumption that a victim should always be believed should be institutionalised".

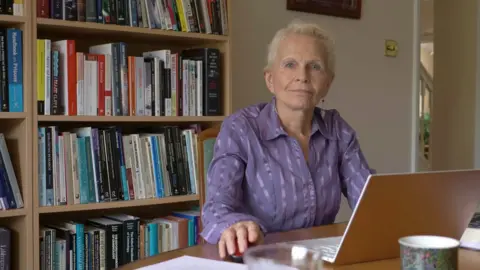

The University of Oxford's Dr Ros Burnett says there is a real danger the "pendulum" of proof in historical cases has shifted too far.

"The trouble with removing all those barriers and making it easier for genuine victims is that you also make it easier for people who, for one reason or another, are accusing the wrong people," she says.

"The possibility of false allegations has almost been airbrushed away. And so there is a sort of complete neglect of the presumption of innocence."

On Friday, Beech was sentenced after inventing claims he was abused by senior politicians - allegations that police once described as "credible and true".

It triggered a £2m investigation that ended without a single arrest being made and led to a controversial call, by then Metropolitan Police chief Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe, to change their approach, and not automatically believe the complainant.

At the time, the NSPCC said in response it was "deeply disturbed" by his comments.

"Telling those who have been sexually abused they will no longer be automatically believed seems to be a panic measure," said a spokesman.

"Police officers should have an open mind and execute the normal tests and investigations."

'I was a wreck'

The wider scale of false allegations is very difficult to measure.

Rape Crisis said earlier this month that false allegations of rape, sexual abuse and other sexual offences were rare but had "disproportionate media focus".

Those representing the accused say even a small number of false allegations can have huge consequences.

Six months after Mr Warr was arrested, he was told a second former pupil had come forward alleging he was abused.

Both complainants were old classmates and friends. Both had already been awarded compensation in a different abuse case at the same school.

Mr Warr says he received threatening emails. A Facebook post said if he killed himself it would be the "best Christmas present ever".

By that stage, Mr Warr adds: "I wasn't eating, I wasn't sleeping. I was a wreck."

It took almost two years for his case to come to trial.

His barrister told the jury he had never taught a single PE lesson. A complainant and a witness both changed key details of their stories. More than 20 ex-pupils, parents and teachers gave evidence in his defence.

It took the jury only 40 minutes to find him not guilty on all seven charges.

Mr Warr cried with relief.

"I'll never get those years back," he says. "But it's not just the fact my life could have been ruined.

"One of the biggest tragedies of cases like mine is that it makes it more difficult for people who have actually been abused to be believed."

'Tied to claims forever'

In a statement, Suffolk Police said: "We collated the available evidence and presented it to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) who made the decision to charge [Mr Warr]."

"The [CPS] lawyer decided that there was sufficient evidence to progress to the courts and that it was in the public interest to prosecute."

The College of Policing has now written to the Home Office to suggest guidance should be changed to say any investigation should be taken forward by police with "an open mind".

Simon Warr left teaching after his trial, saying the publicity made it difficult to get another job.

In recent weeks, the singer Sir Cliff Richard and BBC radio DJ Paul Gambaccini have led calls for the accused to remain anonymous until they are charged.

Last year, the BBC was ordered to pay damages over its reporting of a police raid on Sir Cliff's home during an investigation into historical child sex allegations. He was never arrested or charged.

Mr Warr wants the law to go further.

Since 2012, teaching staff in England and Wales cannot be named until they are charged - but he is campaigning for anonymity until conviction.

"If you are accused of child abuse, you will be inextricably tied to that forever," he says.

"It stays with you for the rest of your life."