Big rise in atmospheric CO2 expected in 2019

Getty Images

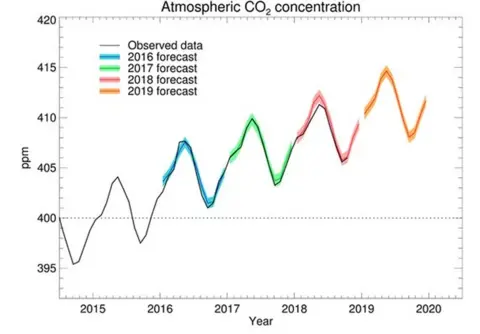

Getty ImagesMet Office researchers expect to record one of the biggest rises in atmospheric concentrations of CO2 in 2019.

Every year, the Earth's natural carbon sinks such as forests soak up large amounts of CO2 produced by human activities.

But in years when the tropical Pacific region is warmer like this year, trees and plants grow less and absorb smaller amounts of the gas.

As a result, scientists say 2019 will see a much bigger CO2 rise than 2018.

Since 1958, the research observatory at Mauna Loa in Hawaii, has been continuously monitoring and collecting data on the chemical composition of the atmosphere.

In the years since they first started recording, the observatory has seen a 30% increase in the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere caused by emissions of fossil fuels and deforestation.

Scientists argue that the increase would have been even larger without the ability of the forests, land and seas to soak up around half of the gas emitted by human activities.

This ability however, varies with the seasons.

Met Office

Met OfficeIn the summer, CO2 levels in the atmosphere fall as the trees and plants soak up more of the carbon as they grow. In the winter, when they drop their leaves, they soak up less and atmospheric levels rise.

But when temperatures are warmer and drier than normal, trees and plants grow less and absorb less. This natural variation is compounded in years when there's an El Niño event, which sees an upwelling of heat from the Pacific into the atmosphere.

"The warm sea surface conditions now will continue over the next few months and that will lead into the vegetation response," said Dr Chris Jones from the Met Office.

"Around the world this heat has different impacts. In some places, it's hotter and drier and you get more forest fires. In a tropical rainforest, for instance, you reduce the natural growth of the vegetation."

According to the Met Office, these limits on the ability to absorb CO2 will see a rise in concentrations this year of 2.75 parts per million, which is higher than the 2018 level.

They are forecasting that average CO2 concentrations in 2019 will be 411ppm. Carbon dioxide concentration exceeded 400ppm for the first time in 2013.

This year's predicted rise won't be as big as in the El Niño years of 2015-16 and 1997-98. However, there have only been increases similar to this year's about half a dozen times since records began.

NOAA/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

NOAA/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARYResearchers say the long-term trend is only going in one direction.

"The year-on-year increase of CO2 is getting steadily bigger as it has done throughout the whole of the 20th Century," said Dr Jones.

"What we are seeing for next year will be one of the biggest on record and it will certainly lead to the highest concentration of CO2."

Other researchers say the Met Office findings are worrying.

"The increases in CO2 are a function of our continued reliance on fossil fuels," said Dr Anna Jones, from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

"Some tempering in the rate of increase arises from the Earth's ability to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, but that can change year-on-year as the Met Office forecast shows.

"What's critical, however, is that the persistent rise in atmospheric CO2 is entirely at odds with the ambition to limit global warming to 1.5C. We need to see a reduction in the rate of CO2 emissions, not an increase."

The Met Office scientists say that it doesn't always follow that a record CO2 concentration will lead to a record global temperature in 2019, as there are many natural factors that can impact the final figure.

The researchers there are pleased that observations over the past four years show that their model is accurate. They believe it can be used in the future to help countries accurately attribute increases in emissions to their actions or to natural factors.

Follow Matt on Twitter.