Monkeypox: Can we still stop the outbreak?

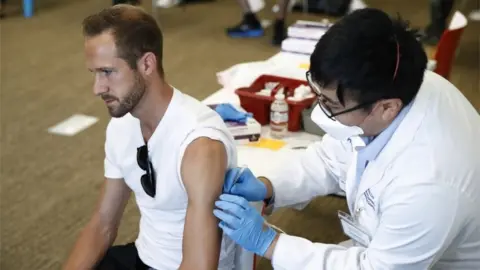

EPA

EPAMonkeypox has caught the world by surprise. It has long been a fixture in parts of central and western Africa where people live close to the forest animals that carry the virus.

But now it has gone global - it is spreading in ways that have not been seen before and on a scale that is unprecedented.

There have been nearly 27,000 confirmed cases of the disease - mostly in men having sex with other men - across 88 countries.

The World Health Organization says this is a global emergency. So can monkeypox be stopped? Or are we now doomed to have another virus spreading around the world?

There are three things we need to consider:

- Is the virus particularly tricky to deal with?

- Do we have the ability to stop it?

- Is there the will to tackle a disease principally affecting gay and bisexual men?

The virus

There's nothing special about the biology of monkeypox virus. It is not an unstoppable force.

Covid probably was - it spreads so readily that it was arguably impossible to contain even in the earliest days of the pandemic.

But monkeypox has a harder time getting from one person to the next. It needs close physical contact - such as through infected skin, prolonged face-to-face contact or contaminated surfaces like a bedsheet or a towel.

The two viruses are simply in different leagues, and past monkeypox outbreaks have just fizzled out.

And we have already overcome the far greater challenge of defeating the virus's deadly cousin, smallpox.

"Monkeypox is easier as it is less transmissible than smallpox so we're in a much better position," said Prof Jonathan Ball, a virologist at the University of Nottingham.

However, one issue is some people have mild symptoms or ones that can be easily mistaken for a sexually transmitted disease or chickenpox. That means it can be unwittingly passed on to others.

The tools

The virus has got into a group of people who are having enough sex or enough intimate contact with enough partners for it to overcome its own inadequacies and spread.

The virus is not a classed as a sexually transmitted infection. But a study in the New England Journal of Medicine estimated 95% of monkeypox infections were being acquired through sex, particularly sex between men.

Sex, obviously, is full of all the intimate skin-on-skin contact that the virus uses to spread.

That leaves two options for containing the disease - persuading people to have less sex; or to reduce the risk of catching the infection when exposed.

Prof Paul Hunter, from the University of East Anglia, said: "The easiest way to prevent it is to close down all highly active sexual networks for a couple of months until it goes away, but I don't think that will ever happen - do you?"

Some people do adjust their sex lives in response to warnings about monkeypox and advice has been targeted at those most at risk.

But Prof Hunter argues the lesson of sexually transmitted infections - from syphilis in the Middle Ages through to now - is that people still have sex and "vaccination is pretty much the only option".

Fortunately, the smallpox vaccine which was used to eradicate that virus is around 85% effective at preventing monkeypox.

There are limited supplies as stockpiles are kept in case of someone weaponising smallpox, not to tackle an unprecedented monkeypox outbreak.

However, not everyone at risk would need vaccinating to stop the outbreak. "Herd immunity" means that once a critical threshold of people are protected the virus can no longer spread. This will be much easier to achieve with monkeypox than other diseases - including Covid.

The people

While anybody can catch monkeypox, it is gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men who are disproportionately affected in this outbreak.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis can make it easier to control the virus as, overall, it is a group that is more clued into sexual health. It also allows resources to be targeted at those who need it - such as vaccinating men having sex with men rather than the whole population.

However, stigma, discrimination and abuse can stop people seeking help, particularly in countries where sex between men is illegal.

"Some countries don't have infrastructure in place and some may not have the will to test for monkeypox, because it's men who have sex with men," said Prof Francois Balloux, from University College London.

There are still challenges in countries that support LGBT - lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender - rights. Even policies such as asking people to isolate - which we're so familiar with from Covid - can have unintended consequences.

"That's tantamount to coming out - whether to a wife or parents [as you suddenly have to explain why] - so there is a strong pressure not to say who your contacts were," said Prof Hunter.

So can monkeypox be contained?

Already some countries do appear to be getting on top of the virus. The UK says the number of infections appears to have levelled off at around 35-a-day. But cases continue to soar elsewhere, including the US which has declared an emergency.

But it won't be enough for just rich countries to get on top of the virus when it's now in more than 80 countries that don't have a long history of the disease.

"It's very unclear to me whether it will be controlled completely, some countries will get on top of it, some might not," said Prof Balloux.

The WHO's technical lead for monkeypox, Dr Rosamund Lewis, says it is "possible" to end the outbreak but warns "we don't have a crystal ball" and it's not clear if the organisation will be able to "support countries enough and communities enough to stop this outbreak."

The endemic countries in Africa - where monkeypox is always there - will continue to deal with the virus as it continually jumps from wild animals into people.

Studies have shown the problem is getting worse since the smallpox eradication programme ended, as few people under 50 will have been immunised.

The only thing that would stop that is a mass vaccination campaign, "but there's a big debate in Africa whether that is appropriate or necessary," says Prof Hunter.

What happens if we don't contain it?

The worry is monkeypox could become a permanent presence in people around the globe rather than just in countries with infected animals.

At the moment that is in men having sex with men, but the longer the outbreak goes on the more chances the virus has to establish itself more widely.

There have been isolated cases in children and women, but these have not kickstarted their own outbreaks in classrooms or workplaces. However, the risks increase as the virus is given time to become better at infecting people. We have witnessed how Covid evolved and variants such as Omicron became so much better at infecting us.

"Unless the virus changes I personally doubt it will spread in children or more generally in people who don't have many sexual partners," said Prof Balloux.

"But the longer the wait, the higher the risk it might change," he said.

The other issue is monkeypox has a knack for infecting a wide range of mammals including squirrels, rats, dormice and monkeys in Africa.

There is a danger that the virus could get a foothold in other animals and start bouncing between species. The 2003 monkeypox outbreak in the US - which led to 47 cases across six states - was driven by pet prairie dogs.

Tackling this outbreak of monkeypox is possible, but the longer we leave it the harder it gets and the greater the risk.

Follow James on Twitter.

Are you having trouble getting the monkeypox vaccine? Share your experiences by emailing [email protected].

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

- WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

- Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay

- Upload pictures or video

- Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at [email protected]. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.