Coronavirus: Could more UK lives have been saved?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt the start of the pandemic, government advisers were saying that 20,000 deaths would be a "good outcome" given what was happening.

The UK has now seen double that - reaching 40,261 deaths on Friday. Was this loss of life inevitable? Or should more lives have been saved?

How bad is our death toll?

It should go without saying, the emergence of a new virus is bound to be a threat to life. Deaths have been recorded in every corner of the globe.

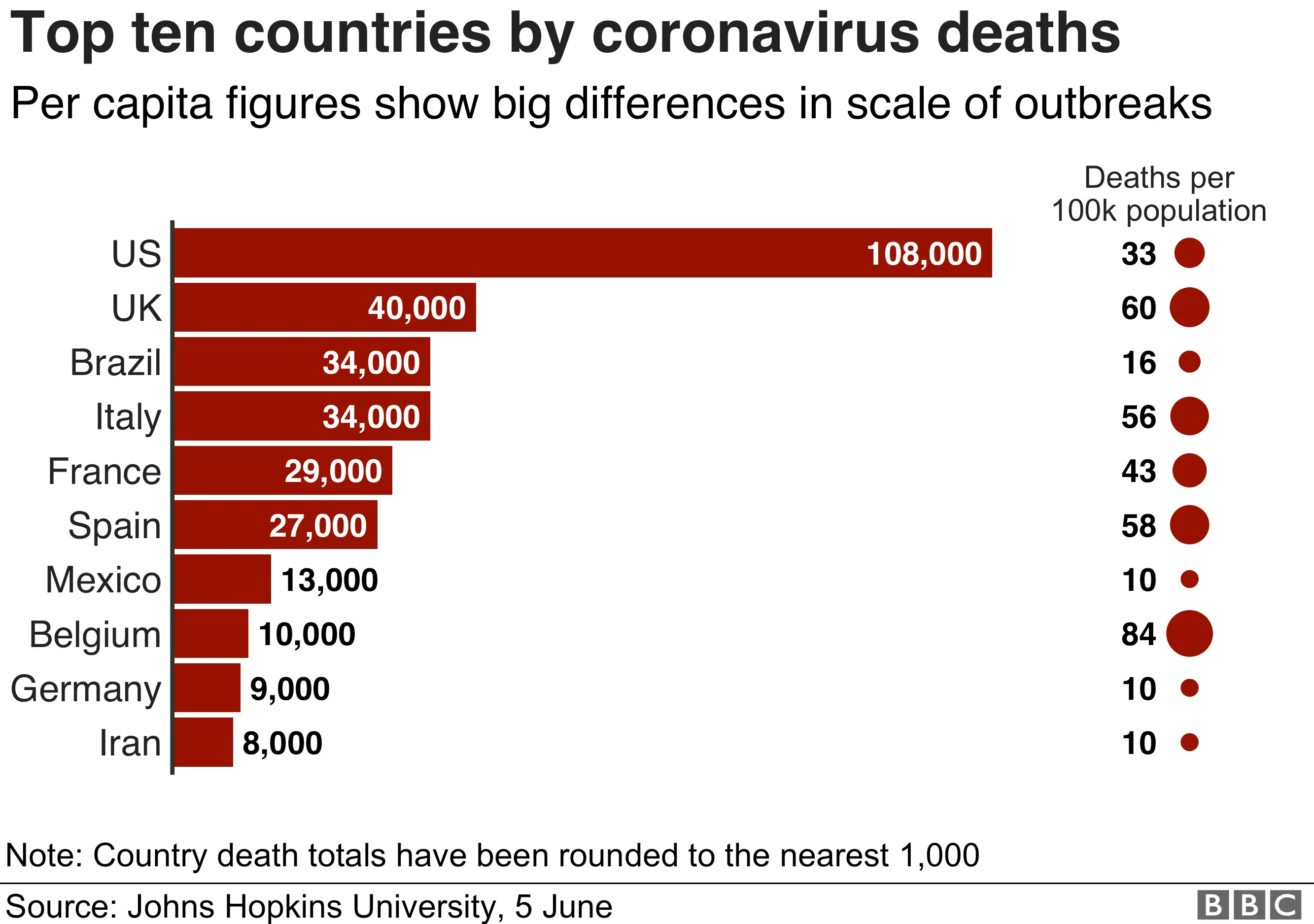

International comparisons are difficult - the way coronavirus fatalities are recorded differs from country to country.

In fact, there are actually two ways to measure coronavirus deaths in the UK. The 40,000 figure refers to deaths following a positive test.

But death certificate mentions, which rely on the judgement of doctors, suggest the UK was actually close to 50,000 deaths by the end of May.

Whichever way you look at it, the UK has certainly been among the worst affected countries.

However, the UK is not an outlier. A number of our near neighbours - in particular Spain and Italy - have seen similar rates of fatalities if use deaths per head of population.

The UK was vulnerable

The UK was always going to face a challenge dealing with a virus that was both infectious and - for some - deadly.

With London being a global hub, the virus arrived quickly. The first documented case was in February, but there are suggestions it was circulating before then.

The capital also provided the perfect breeding ground, with its large and densely packed population. It is no coincidence that London saw a surge ahead of the rest of the UK.

Combine that with the ageing population across the country - the elderly are the most at risk of dying if infected - and it's clear the demography of the UK left it vulnerable.

Were we under-prepared?

Of course, competent governments put plans in place to mitigate these sort of risks. Just last year a review was suggesting the UK was one of the best prepared countries for a pandemic.

We may have been - if it had been flu.

The procedures used in the early days - the so-called contain, delay and mitigate action plan - were based on the strategy for influenza not coronavirus. Prof Devi Sridhar, chairwoman of global public health at Edinburgh University, says this led to the assumption the virus could not be contained and instead had to be managed.

Our leaders, she says, "failed to grasp the gravity of the situation".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOther countries, such as Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea, thought and acted differently. With experience of dealing with the likes of Sars and Mers, the countries already had established testing and tracing networks in place. They were quickly deployed and between them they have seen around 300 deaths, despite having a combined population greater than the UK.

Prof Sridhar says the approach of the UK smacked of "complacency" - but it is a criticism she also levels at the US and other European countries.

Jeremy Hunt, chair of the House of Commons' health committee and a former health secretary, has gone even further, describing the failure to learn from Asian countries as "one of the biggest failures of scientific advice to ministers in our lifetime".

Did we take too long to lock down?

You could argue these criticisms are being levelled with a degree of hindsight. But even if you give the UK the benefit of the doubt for the lack of preparedness, when the gravity of the situation became clear were we too slow to act?

By early March, government modellers had realised the virus was more widespread than had previously been assumed and with distressing scenes from Italy beginning to emerge, the government announced its next steps.

Some measures started to be put in place, including asking people to isolate at home if they developed symptoms. But full lockdown was not announced until 23 March.

During that time people were travelling around the country, commuters flooded in and out of London on busy trains, tubes and buses and major sporting events continued, including the Cheltenham Festival.

Prof Sir David King, a former government scientific adviser, has argued it is clear we reacted "too late", warning every day of delay "cost lives".

Modelling carried out for Channel Four Dispatches programme has suggested a lockdown on 12 March could have saved 13,000 lives, while one on 16 March might have saved 8,000.

Mistakes made on testing

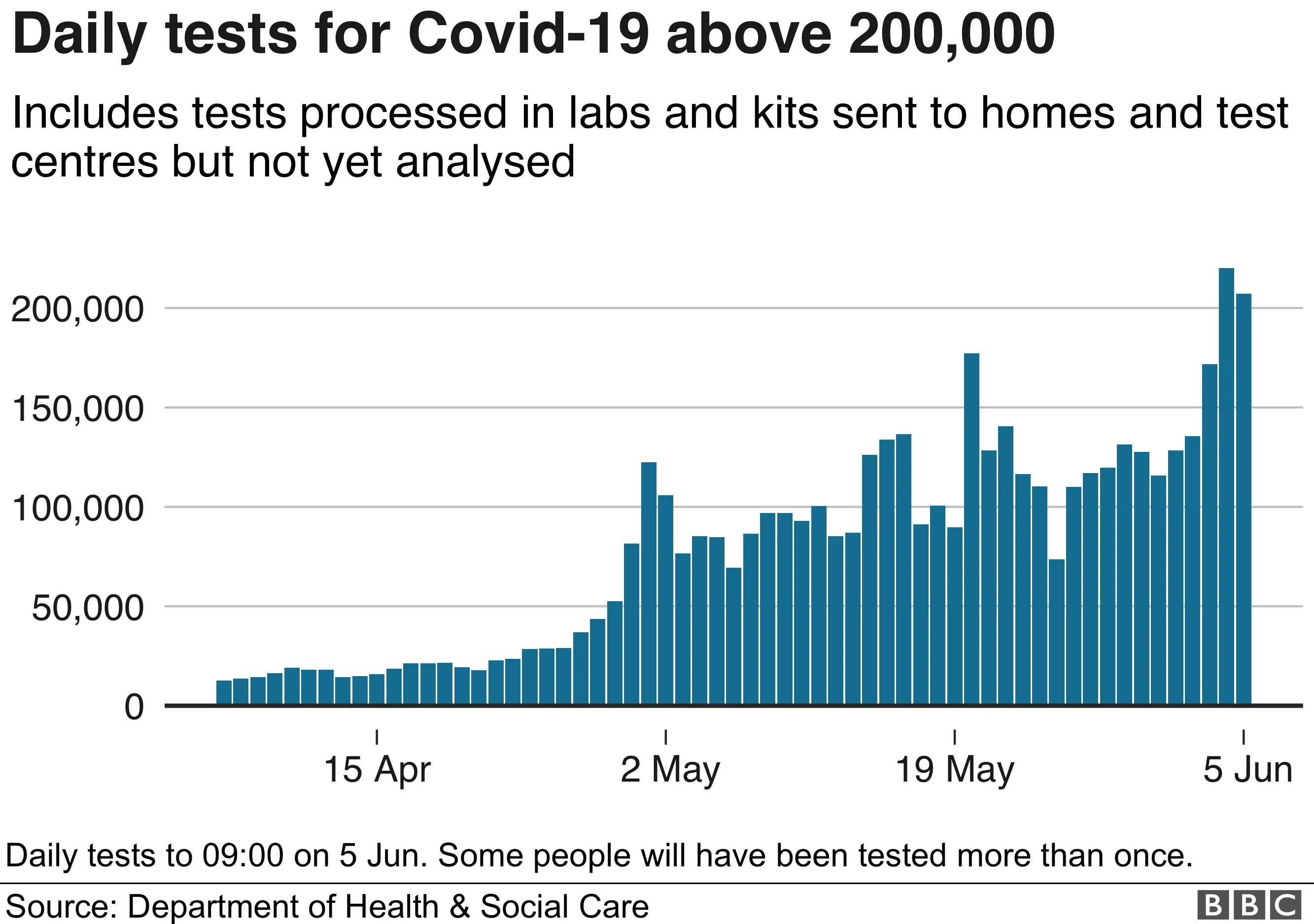

The key to tackling coronavirus, according to the World Health Organization, was always "test, test, test". But the problem was the UK did not do this.

In the early days of the pandemic, the government was quick to boast about its testing capacity. The ability to carry out 1,000 tests was quickly increased to 3,000. But as the outbreak spread, it quickly became clear there were not enough tests to go round.

In mid-March the decision was taken to stop offering tests to people in the community so they could be reserved for hospital patients. Public Health England and health officials in the rest of the UK relied on eight small labs and their own testers at the time.

That policy remained in place for weeks before the government entered into serious discussions with hospitals, universities and the private sector to increase testing capacity. It meant it was late April before it was able to test tens of thousands of patients a day as countries like Italy and Germany were doing.

Quizzed on this recently by MPs, government officials admitted it would have been "beneficial" to have ramped up testing more quickly.

- TRIBUTES: Remembering those who died

- THE R NUMBER: What it means and why it matters

- LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

- GLOBAL SPREAD: Tracking the pandemic

Care homes have undoubtedly suffered

Care homes, where nearly a third of deaths have happened, have perhaps been affected by the lack of testing more than anywhere else. Until mid-April tests were stopped once a care home passed five positive cases. What is more, staff and residents not showing symptoms were unable to get a test until late April despite concerns asymptomatic transmission was unwittingly causing outbreaks.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSubsequent research has suggested in some care homes nearly half of staff and residents who have tested positive for coronavirus have not been showing symptoms.

Sam Monaghan, chief executive officer of MHA, which runs 90 care homes, says this has cost lives.

"A lot of people may not have ended up dying if we had earlier testing and we'd been better able to manage infections."

Lessons will be learnt

The problems have been further compounded by lack of protective equipment for staff - aprons, gloves and visors were prioritised for the NHS.

The experience of other countries, including Canada, Israel and Germany, along with those in south-east Asia, shows high numbers of deaths are not inevitable however. As well as testing and protective equipment, there has been a specific focus on ensuring agency staff do not move from home to home.

High vacancy rates in the UK mean many homes are heavily reliant on agencies.

Everyone from public health directors and town hall chiefs to hospital bosses agree the historic under-funding of the care sector has left it particularly vulnerable. The handling of the pandemic in care homes - and across the whole of society for that matter - will undoubtedly be pored over in years to come.

A public inquiry seems inevitable. It will no doubt show mistakes have been made.

In a recent blog, the government's chief scientific adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance, admitted as much himself. In years to come, he wrote, I know we will look back and we will have learned a lot - including how to do it better next time.

Follow Nick on Twitter