Brexit: What does it mean for security in the UK?

Associated Press

Associated PressIf the UK cannot reach a deal with the EU over their future relationship, it will have enormous security implications.

The UK will crash out of more than 30 EU criminal justice bodies which every day help keep people across Europe safe.

There's widespread concern among police chiefs about losing these tools and powers.

But Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab told the BBC's Andrew Marr programme that UK security would improve after Brexit.

He added the UK still wanted access to some of these EU tools as part of "common sense co-operation".

So what powers are the police worried about losing?

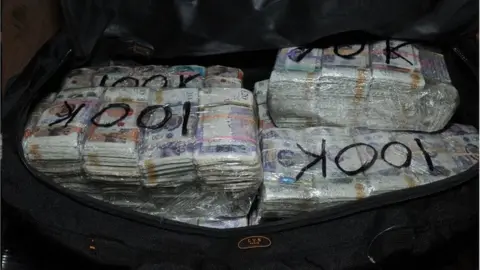

Catching organised criminals

One of the biggest recent victories against crime came when French investigators cracked the encrypted "Encrochat" network and obtained secret messages sent between gangsters across Europe.

That operation was an unprecedented success, leading to hundreds of arrests, including in the UK.

Essex Police

Essex Police The EU's policing agency, Europol, played a central role sending the French evidence to the right teams across Europe - and co-ordinating the timing for their raids.

From 2021, the UK will no longer be a full member of Europol because it's an EU agency.

The National Crime Agency (NCA) says it will have to reorganise hundreds of cross-border operations through new agreements with each nation it currently works with inside Europol.

Some nations, like the USA, have an "associate" relationship with Europol - but can't use all its investigatory powers, and have no say over its objectives and priorities. The UK faces similar questions over its relationship to a second agency, Eurojust, which predominantly links up prosecutors.

Capturing the most wanted

In 2005, failed London bomber Hussain Osman was arrested in Italy and brought back to the UK for trial in only 56 days, thanks to the European Arrest Warrant (EAW).

Metropolitan Police

Metropolitan PoliceThe UK has found, arrested and extradited 11,300 people in the decade to 2019 - and received 1,600 suspects wanted for crimes here.

The UK will leave the EAW. Extradition is still possible under a 1957 treaty - although not from Germany. History shows the hardest cases could take a decade to resolve amid multiple appeals.

Norway and Iceland have an extradition agreement with the EU, because they joined its borderless travel system.

The power of databases

When front-line police officers receive alerts about wanted or missing people, cars or other items, some come from an enormous EU-wide database called SIS 2.

Searching its 91 million entries is integrated into everyday work by UK police, who access it about half a billion times annually.

This example from the government's own Brexit papers illustrates its strengths.

In June 2016, Portugal uploaded an alert about a drug trafficker. The UK's systems spotted someone flying into the country matched the suspect - leading to their arrest and return to Portugal within a fortnight.

There are other databases too:

- Ecris - the pan-European system for checking criminal records

- Prüm - a system that connects DNA and crime fingerprint records used by police across Europe. The NCA says Prüm, named after the German town where it was agreed, has helped identify suspects in 500 investigations

- Eurodac - a migration fingerprint system to track multiple asylum claims by the same individual

At the end of 2020, the Home Office unplugs SIS 2 and the other databases because they are governed by EU laws.

Last month, Martin Hewitt, National Police Chiefs Council head, said losing SIS 2 would have "a major operational impact".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMany front-line officers fear that if they can no longer quickly access information, it may be impossible to hold some suspects they find.

Losing Prüm is considered to be equally as damaging.

The UK hopes Interpol's systems can fill some of the gap. But that's nowhere near as automated, detailed or as comprehensive as SIS 2. The NCA has recruited 60 officers just to try to make this work.

The UK will also have to send time-consuming manual requests for data like DNA profiles. EU police should act on these under an existing treaty - but delays could make or break a manhunt.

Gathering evidence abroad

Say British police need to speak to a man in Spain who may be a suspect in a crime in Birmingham.

Currently they can send a "European Investigation Order" to their Spanish colleagues - a legally-binding request to gather evidence by a specific deadline.

However, the UK won't be part of the system as it is an EU legal tool, so in the future must send an historically slow "Letter Regatory" - an internationally-recognised diplomatic request for help.

However, nations sometimes ignore them, take too long to respond or, in the worst case scenario, use a request as a political bargaining chip.

Joining the dots - uncovering patterns

Another database covering travellers, known as Passenger Name Record (PNR) allows investigators to analyse the movements of suspects and spot patterns across Europe.

In another example in UK Brexit documents, when a woman from Togo was rescued from sex trafficking in the UK, police found a gang member's phone number.

PNR linked it to other flight bookings in the EU - and identified other trafficking victims they would not otherwise have discovered.

It is unclear what happens next. The US and Australia have some PNR access - but cannot carry out the deep-dive analysis that reveals bigger patterns.