UK’s chief medical officers dashed PM’s ‘hopes’ to lower Covid alert

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere is no judgement more important right now than gauging the trade-off between reopening the economy and the measures limiting the spread of coronavirus.

But the BBC understands that all four chief medical officers of the UK nations, including England's Professor Chris Whitty, opposed the prime minister's hopes of lowering the Covid-19 alert level last week.

Less than a month ago, Boris Johnson announced that any easing of the lockdown would be conditional on a lower alert level, alongside "five tests" on the spread of infection being met.

Indeed, when the prime minister promised on 10 May to ease the lockdown around open air markets and primary schools, as happened on Monday, he issued an important caveat: "If the alert level won't allow it, we will simply wait and go on until we have got it right."

The next day, the government's "Plan to Rebuild" said that the changes to the lockdown "must be warranted by the current alert level".

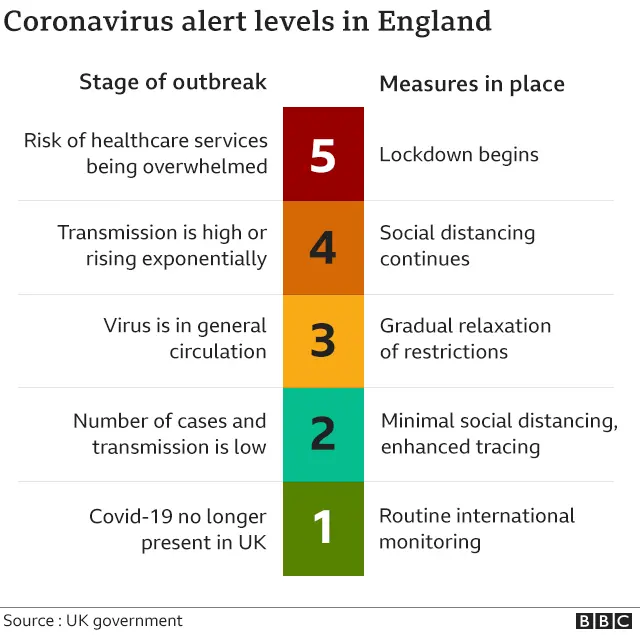

At that time the alert level was 4, indicating that "transmission is high or rising exponentially".

At level 3, transmission is no longer considered "high" but a Covid-19 epidemic is in general circulation. Level 3 justifies "gradual relaxing of restrictions and social distancing measures".

On Wednesday last week, the prime minister told parliament's Liaison Committee that "we're coming down the Covid alert system from level 4 to Level 3 tomorrow, we hope, we're going to be taking a decision tomorrow".

That was in reply to a question from the Northern Ireland Select Committee chair Simon Hoare about the PM's adviser Dominic Cummings.

But the next day, the government decided instead not to lower the alert level.

There were two other important meetings that day. One was between the four nations' chief medical officers. The other was between the devolved governments and the PM, and easing the alert level across the UK was expected to be discussed.

Getty Images

Getty Images"It was clear that government wanted to change it and scientists and the chief medical officer didn't," said one political source involved.

This account was later confirmed to me by a scientist involved in pandemic planning, and sources in three governments said that all four chief medical officers from England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland did not back the hoped-for move to alert level 3.

The government itself has not confirmed or denied this account, only suggested that it was "always clear" that the alert level was not the primary reason for easing lockdown.

But the doubts harboured by the country's most senior medical adviser, and other scientists, about lowering the alert level do matter.

The government pressed on with the modest easing of the lockdown, even after the PM's promise last month that any relaxation would be conditional on a lowering of the alert level.

In early May measures such as reopening primary schools and markets were promised "no earlier" than 1 June.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLast week, ministers were left describing how the alert level was "transitioning to 3" to justify going ahead with easing the lockdown, even as the level technically remained at 4.

But at the government's daily coronavirus briefing last Thursday, chief scientific adviser Sir Patrick Vallance made a point of saying that the number of cases "remain high - it's not a low number" and that in some places the transmission rate, or R-value, remained "close to 1".

He added that the UK remained in a "fragile state" and should be prepared to re-impose measures if necessary.

Over the weekend, a series of senior members of the Sage advisory committee announced that the easing of lockdown was premature.

Then there is a more significant question about who actually decides the alert level. The prime minister had said last month that it should be the Joint Biosecurity Centre (JBC).

Tensions

When I asked at last Friday's government briefing what the centre had said, NHS medical director Prof Stephen Powis replied that the JBC was "currently under development setting itself up" and "feeding information into the four chief medical officers who have to think about alert levels".

But on Tuesday, Number 10 confirmed that this would no longer be the case, and it was "ultimately" the UK chief medical officers' job to set the alert level using analysis from the JBC which has now "begun operating".

And that raises another key concern.

It is my understanding that there are some tensions between administrations, and some of this spilt out into the teleconference last Thursday. The Joint Biosecurity Centre has not been signed off by the devolved administrations.

Some expressed disappointment that the government's Cobra civil contingencies committee had not met in the three-week period before the latest round of lockdown easing was confirmed in Westminster.

The prime minister pointed to what he saw as particular problems in Scottish care homes, and also mentioned north Wales as a Covid-19 hotspot, although scientists say that this is due to a change in measurement.

No transition

The Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon and the prime minister "locked horns" on the care home issue, I'm told. Another source says the half hour call "was supposed to be about the alert level, but the doctors and scientists had already killed off the move".

Even if the medics had agreed, it is quite plausible that the Scottish and Welsh governments would have refused to lower the alert level.

Cabinet Office minister Michael Gove is expected to make an effort to keep Welsh and Scottish administrations onside.

Other experts point out that applying a terror alert-style system to pandemics simply might not work, as the government's own decisions have a significant direct impact on transmission rates, unlike terrorism.

The terror alert system also has no transition state between its levels. And there are questions about whether this new system is meant to replace the Sage experts, and why exactly that is happening.

The fear is that this vital new policy development, designed to clearly communicate risk levels across the nations of the UK to workers, businesses, parents and pensioners has more than just teething problems.

The government is now downplaying the importance of the system to lifting lockdown. The concern is that the system, explained in some detail by the PM in an address to the nation, now risks being dead on arrival.