How much money does the UK government borrow, and does it matter?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe UK government generally spends more than it raises in tax.

To fill this gap it borrows money, but that has to be paid back - with interest.

Why does the government borrow money?

The government gets most of its income from taxes. For example, workers pay income tax and National Insurance, everyone pays VAT on certain goods, and companies pay tax on profits.

It could, in theory, cover all of its spending from taxes and that sometimes happens.

But, if it can't, the government covers the gap by raising taxes, cutting spending or borrowing.

Higher taxes mean people have less money to spend, so businesses make less profit, which can be bad for jobs and wages. Lower profits also mean companies pay less tax.

So, governments often decide to borrow to boost the economy. They also borrow to pay for big projects, like new railways and roads.

How does the government borrow money?

The government borrows money by selling financial products called bonds.

A bond is a promise to pay money in the future. Most require the borrower to make regular interest payments.

UK government bonds - known as "gilts" - are normally considered very safe, with little risk the money will not be repaid.

Gilts are mainly bought by financial institutions in the UK and abroad, such as pension funds, investment funds, banks and insurance companies.

The government sells short and long-term gilts to allow it to borrow money over different time periods, with varying interest rates.

How much is the UK government borrowing?

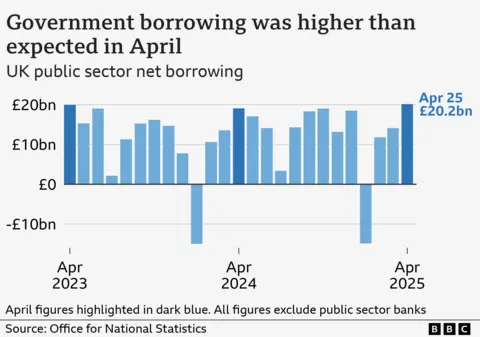

The amount the government borrows fluctuates from month to month.

For instance, it tends to borrow less in January, when many people pay a large chunk of their annual tax bill in one go.

So, it is more helpful to look across a whole year, or the year-to-date.

In the last full financial year, to March 2025, the government borrowed £148.3bn.

Borrowing in April alone stood at £20.2bn, which was £1bn more than a year earlier.

The total amount the government owes is called the national debt. It is currently about £2.8 trillion - or £2,800,000,000,000.

That is roughly the same as the value of all the goods and services produced in the UK in a year, known as the gross domestic product, or GDP.

The current level is more than double that seen from the 1980s through to the financial crisis of 2008.

The combination of the financial crash and the Covid pandemic pushed the UK's debt up.

But, in relation to the size of the economy, UK debt figures are still low compared with much of the last century. They are also less than the equivalent figures for some other leading economies.

How much money does the government pay in interest?

The larger the national debt, the more interest the government pays.

That cost was not as great when interest rates were low during the 2010s, but became more noticeable after the Bank of England started raising interest rates in 2021.

The amount of interest the government pays on national debt also varies from month to month.

It was £9bn in April 2025, a fall of £500m compared with the previous year.

In early January 2025, interest rates for long-term borrowing rose to their highest levels this century, before falling back.

Why does it matter if governments borrow more and pay more interest?

If the government has to set aside more cash for paying debts and interest, it may mean it has less to spend on public services.

Some economists fear the government is borrowing too much, at too great a cost. Others argue extra borrowing helps the economy grow faster - generating more tax in the long run.

The increase in projected long-term interest rates seen in January prompted some economists to warn that the government was on course to miss its own borrowing targets.

Labour decided to stick to a rule followed by the previous government that the total amount of money owed must have fallen as a proportion of the UK economy in five years' time.

In October's Budget, Chancellor Rachel Reeves changed the definition of debt that the government would use in the target to enable her to raise more money for investment.

It will now track a different, broader measure of debt called public sector net financial liabilities (PSNFL). This includes, for example, the money the government gets from people repaying their student loans.

Downing Street said there was "no doubt about the government's commitment to economic stability", and that "meeting our fiscal rules is non-negotiable".

What is the difference between debt and deficit?

Debt is the total amount of money owed by the government that has built up over years.

The deficit is the gap between the government's income and the amount it spends.

When a government spends less than its income, it has what is known as a surplus.

Debt rises when there is a deficit, and falls in those years when there is a surplus.