UK pay squeeze tightens but unemployment dips

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWages continue to lag behind the cost of living in the UK, while unemployment remains at a 42-year low.

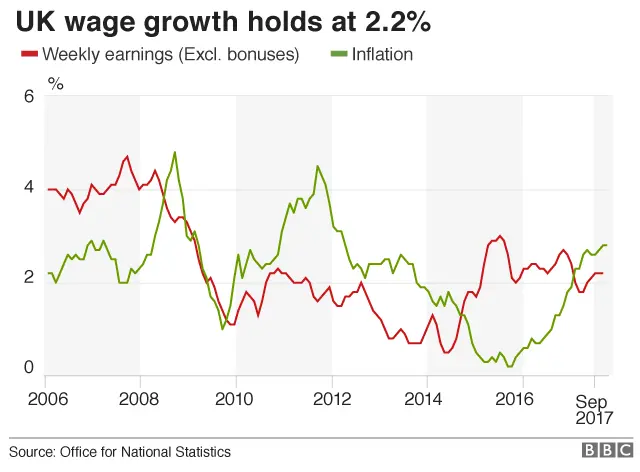

Workers' earnings, excluding bonuses, rose 2.2% in the three months to September compared with a year ago, the Office for National Statistics said.

But they fell 0.5% in real terms when accounting for inflation, marking seven months of negative pay growth.

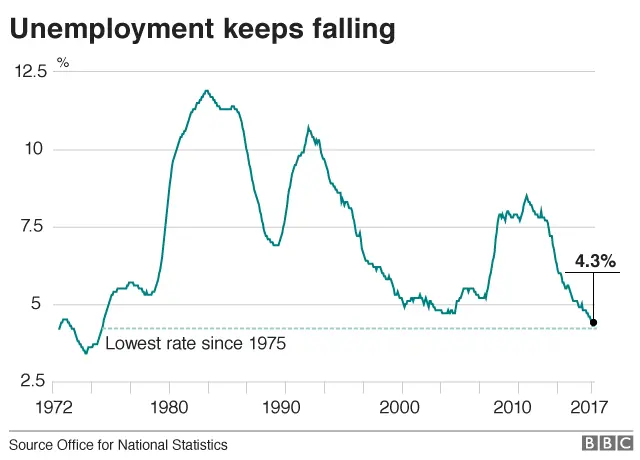

The number of jobless - people not in work but seeking a job - fell 59,000 to 1.42 million during the period.

With inflation at a five-and-a-half-year high of 3% in October, pay is failing to keep up with higher prices.

The unemployment rate remained steady at 4.3% - its lowest rate since 1975 - and down from 4.8% a year earlier.

Minister for Employment Damian Hinds said the unemployment figures showed the "strength of the economy".

"A near-record number of people are now in work," he said. "Everyone should be given the opportunity to find work and enjoy the stability of a regular pay packet."

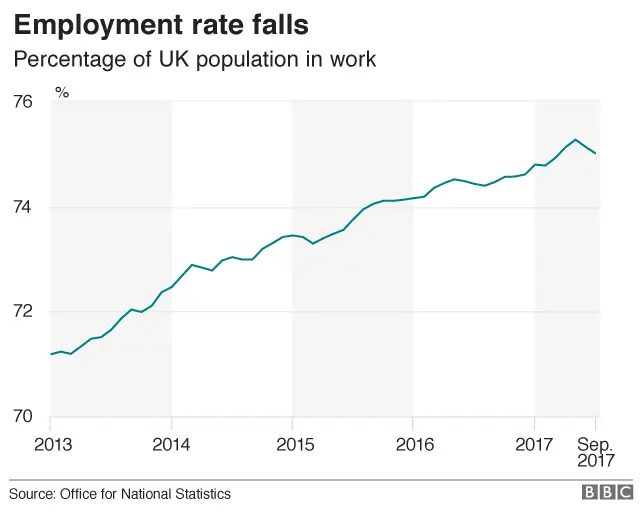

At the same time, the number of people in work dropped to 32 million, down 14,000 from the last quarter, according to ONS data.

Labour MP Debbie Abrahams, shadow work and pensions secretary, said the figures were further evidence of "Tory economic failure".

She said: "Both employment and real wages are falling while the price of household essentials balloons, leaving millions of people worse off than they were in 2010."

Matt Hughes, a senior ONS statistician, said employment had declined after two years of "almost uninterrupted growth", but was still higher than last year.

The last time there was a bigger fall in employment was in April to June 2015, when the number of people in work dropped by 45,000, according to the ONS.

The simultaneous drop in the number of workers and unemployed people is due to the rise in people who are classed as "economically inactive" - those not working and not seeking or available to work.

This includes people studying, retirees, the long-term sick, or those looking after family, and rose by 117,000 to 8.8 million over the quarter.

Mr Hughes said: "There was a rise in the number of people who were neither working nor looking for a job - so-called economically inactive people."

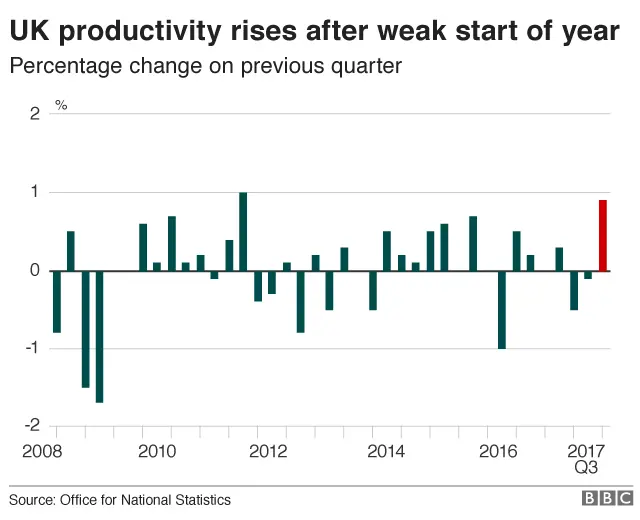

Separate ONS data showed a bright spot for productivity, which increased by 0.9% in the latest three months - the strongest growth rate for six years.

But this follows a prolonged period of weak productivity since the financial crisis.

Productivity: A volatile measure

By BBC economics editor Kamal Ahmed:

Any port in a storm, but it is sensible to put today's leap in productivity in context.

After six months of negative figures (-0.5% January to March, -0.1% April to June), today's +0.9% jump in productivity is undoubtedly better news.

But it would need at least two more quarters of similarly positive numbers to discern whether this is just normal quarter-by-quarter volatility or the first signs that the productivity slump might be starting to turn.

The ONS measures productivity by dividing the number of hours worked by what is called Gross Value Added, the value of goods and services produced by the UK economy.

It has leapt this quarter because working hours have fallen slightly and economic growth is higher.

Whether we are actually producing more per hour worked - the key to wealth creation and better wages - will only become clear over the next six months.

ONS head of productivity Philip Wales said: "The medium-term picture continues to be one of productivity growing - but at a much slower rate than seen before the financial crisis."

The CBI's head of employment, Matthew Percival, thought the rise in productivity was "encouraging".

He said: "Businesses will be looking for the chancellor to cement progress in next week's Budget and maintain flexibility in the labour market, which remains a mainstay of the UK economy."

Fewer employed and unemployed?

By BBC business correspondent Jonty Bloom:

How can unemployment and the number of people in work drop at the same time?

The unemployment rate is a measure of those people who want to work - and cannot - but the employment rate is a measure of everyone in work.

So you could have a large number of people retiring and only some of them being replaced by unemployed people who are recruited to do their jobs.

Employment will fall, and so will unemployment.

In today's figures, the fall in employment seems to be concentrated amongst the 18-24 year olds, suggesting that part of the reason is that they are returning to education, although the figures are supposed to take such seasonal factors into account.