How formula milk shaped the modern workplace

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt sounded like cannon fire - pirates, probably. The British East India Company's ship Benares was docked at Makassar, on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. Its commander gave the order to set sail and hunt them down.

Three days later, the crew still hadn't found any pirates. What they had actually heard was the eruption of a volcano called Mount Tambora.

A cocktail of toxic gas and liquefied rock roared down the volcano's slopes at the speed of a hurricane, killing thousands. Mount Tambora was left 4,000ft (1,220m) shorter.

The year was 1815. Slowly, a vast cloud of volcanic ash drifted across the northern hemisphere, blocking the Sun.

In Europe, 1816 became "the year without a summer". Crops failed. Desperate people ate rats, cats and grass.

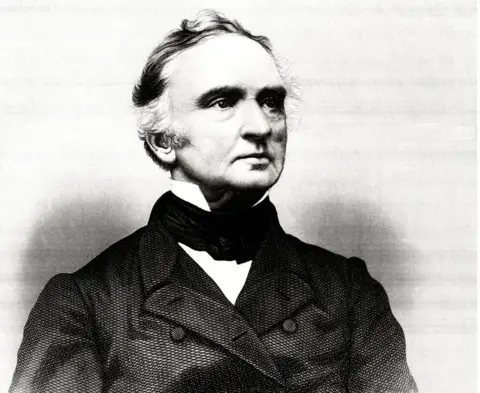

In the German town of Darmstadt, the suffering made a deep impression on a 13-year-old boy. Justus von Liebig loved helping out in his father's workshop, concocting pigments, paints and polishes.

Rigorous study

Liebig grew up to be a brilliant chemist, driven by the desire to help prevent hunger. He did some of the earliest research into fertilisers. He pioneered nutritional science and invented beef extract.

He invented something else, too: infant formula.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Launched in 1865, Liebig's Soluble Food for Babies was a powder comprising cow's milk, wheat flour, malt flour and potassium bicarbonate.

It was the first commercial substitute for breast milk to come from rigorous scientific study.

As Liebig knew, not every baby has a mother who can breastfeed.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIndeed, not every baby has a mother: before modern medicine, about one in 100 childbirths killed the mother. It's little better in the poorest countries today.

Some mothers can't make enough milk - the figures are disputed, but could be as high as one in 20.

What happened to those kids before formula?

Parents who could afford it employed wet-nurses - a respectable profession for the working girl, and an early casualty of Liebig's invention. Some used a goat or donkey.

Good timing

Many gave their infants "pap", a bread-and-water mush, from hard-to-clean receptacles that must have teemed with bacteria.

No wonder death rates were high: in the early 1800s, only two in three babies who weren't breastfed lived to see their first birthday.

Liebig's formula hit the market at a propitious time.

Alamy

AlamyGerm theory was increasingly well understood, and the rubber teat had just been invented. The appeal of formula quickly spread beyond women who couldn't breastfeed.

Liebig's Soluble Food for Babies democratised a lifestyle choice that had previously been open only to the well-to-do.

It's a choice that now shapes the modern workplace. For many new mothers who want - or need - to get back to work, formula is a godsend.

And women are right to worry that taking time out might damage their careers.

Earnings gap

Recently, economists studied the experiences of the high-powered men and women emerging from Chicago University's MBA programme and entering the worlds of consulting and high finance.

At first, the women had similar experiences to the men - but over a time, a huge gap in earnings opened up. The critical moment? Motherhood. Women took time off, and employers paid them less in response.

Ironically, the men were more likely than the women to have children. They just didn't change their working patterns.

AP

APThere are biological and cultural reasons why women are more likely than men to take time off when they start families.

We can't change the fact that only women have wombs, but we can try to change workplace culture.

More governments are following Scandinavia's lead by giving fathers the legal right to take time off. More leaders - such as Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg - are setting an example by taking it.

And formula milk makes it a whole lot easier for Dad to take over while Mum gets back to work. There is, of course, the breast-pump option. But for some, it's more of an effort than formula.

Studies show that the less time mothers have off work, the less likely they are to persevere with breastfeeding. That's hardly surprising.

There's just one problem. Evolution has had thousands of generations to optimise the recipe for breast milk.

And formula doesn't quite match it, especially in the developing world, where clean water and sterilised equipment is not always available.

A series of articles published by the medical journal the Lancet in 2016 lists the risks. Formula-fed infants get sick more often than breastfed children, leading to costs for medical treatment, and parents taking time off work.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt's thought that nearly half of all diarrhoea episodes and a third of all respiratory infections could be prevented by breastfeeding.

That, combined with the risk of using formula in less than ideal circumstances, can even lead to deaths.

According to the Lancet's analysis of more than 1,300 studies, breastfeeding could prevent about 800,000 child deaths a year.

Justus von Liebig wanted to save lives. He would be horrified.

Economic cost

Of course, in rich countries, contaminated milk and water are far less of a concern.

But formula has another, less obvious economic cost.

Again, according to the Lancet, there is evidence that breastfed babies grow up with slightly higher IQs - about three points, when you control as best you can for other factors.

What might be the benefit of making a whole generation of children just that little bit more clever?

The Lancet calculated it to be about $300bn (£232bn) a year. That's several times the value of the global formula market.

Consequently, many governments try to promote breastfeeding. But nobody makes a quick profit from that. Selling formula, on the other hand, can be lucrative.

More from Tim Harford

Which have you seen more of recently: public service announcements about breastfeeding, or formula ads?

Liebig himself never claimed that his Soluble Food for Babies was better than breast milk: he simply said he'd made it as nutritionally similar as possible.

Nestle controversy

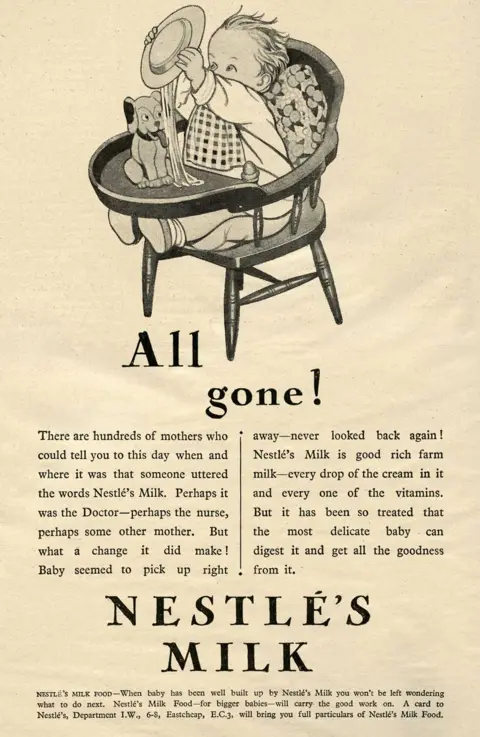

But he quickly inspired imitators who weren't so scrupulous. By the 1890s, adverts for formula routinely portrayed it as state-of-the-art.

Meanwhile, paediatricians were starting to notice higher rates of scurvy and rickets among the offspring of mothers whom the advertising swayed.

Alamy

AlamyThe controversy peaked in 1974, when the campaigning group War on Want published a pamphlet called The Baby Killer about how Nestle marked and sold infant formula in Africa. Nestle boycotts lasted years.

By 1981, there was a World Health Organization (WHO) International Code of Marketing Breast-milk Substitutes, which Nestle says it drew on to devise its own marketing code, the first manufacturer to do so.

But the WHO code is not hard law, and many campaigners argue that it is still widely flouted.

Supply chain

What if there was a way to get the best of all worlds: equal career breaks for mothers and fathers, and breast milk for infants, without the faff of breast pumps? Perhaps there is - if you don't mind taking market forces to their logical conclusion.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn Utah, there's a company called Ambrosia Labs. Its business model? Pay mothers around the world to express breast milk, screen it for quality, and sell it on to American mothers.

Milk is pricey - over $100 (£77) a litre (1.75 pints). But that could come down with scale - and maybe formula could be taxed, to fund a breast-milk market subsidy.

Not everyone likes this idea. Indeed, the government in Cambodia, where Ambrosia used to operate, has banned the export of breast milk.

Still, more than 150 years after Justus von Liebig sounded the death knell for wet nursing as a profession, perhaps the global supply chain could find a way to bring it back.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.