'Let out the poison' - new study aims to find the truth on NI abuse

BBC

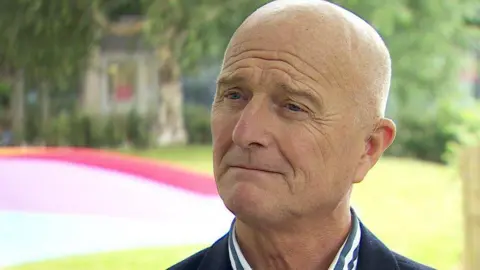

BBCTony Gribben describes "cowering like a dog", as he was "beaten down" by his abuser at his boarding school.

"The violence meted out on me was both physical and sexual," Mr Gribben said.

Many survivors want an independent public inquiry into the abuse they suffered by clergy and other religious leaders in Northern Ireland.

The devolved Northern Ireland government is now considering how to deal with the issue and has commissioned a study, which Mr Gribben describes as a "critical step forward".

Warning: This page contains distressing details

PACEMAKER

PACEMAKERThe research is gathering the stories of survivors of abuse in what are termed "faith settings" – which can include churches, schools and other places where clergy and leaders in religious organisations abused children.

Mr Gribben said the abuses he suffered began during his first year in boarding school.

"It started with beatings around the head. On reflection, I understand this was part of his tactics – beating me down," Mr Gribben said.

"Then it moved on to general sexual assault – like hands down sweaters, fondling, kissing – and culminated in extreme sexual violence."

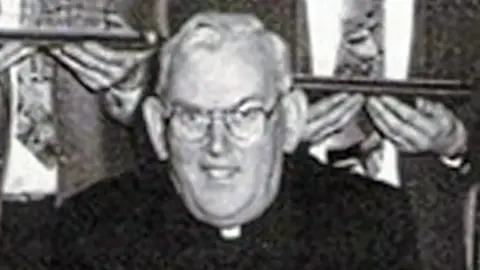

Mr Gribben was abused by Father Malachy Finegan, who died in 2002.

He was accused of multiple sexual assaults on boys, including at St Colman's College in Newry, County Down, where he became headteacher.

But he was never prosecuted or questioned by police.

Mr Gribben and the survivor support network, the Dromore Group, want an independent public inquiry into clerical abuse in Northern Ireland.

'How do I deal?'

"It's the lived experience which touches on people's hearts," says Mr Gribben, who is encouraging people to take part in the project.

"It is through disclosure that you empower yourself."

Mr Gribben decided to report the abuse he suffered to the police in 2019, when he was coming to the end of his career.

"I was preparing for my retirement, and all this came flooding back," he said.

"The box reopened, and I was moving into the last phase of my life.

"I thought, how do I deal with this?"

He is keen to help spread the word about the research to other survivors who, like himself, live abroad.

"One common factor amongst those who have been abused as children is that they tend to move away from the environment where they lived. There are too many triggers for them to have a normal life," he explained.

"Part of me believes that as survivors we've become strong in our numbers, and our voice is being heard.

"I'm confident the administration in Northern Ireland is taking this issue seriously."

'A lack of accountability'

Nikella Holmes agrees that "survivors aren't being quiet any more".

She was abused by a youth leader at her former church, Gary Thompson, who was jailed last year.

"We are coming into a new age where we see survivors are strong people. That's what's going to bring change," she told BBC News NI.

"For me, it took a long time to believe that I was abused.

"Sometimes we can use Christian principles like forgiveness to try to leave behind what happened.

"That's never going to work with this kind of trauma."

She has taken part in the research and is particularly encouraging people from a Protestant background, like her, to come forward.

"We have heard a lot about abuse in the Catholic Church – we haven't heard a lot of stories from people with a Protestant background.

"I have no doubt those stories are there."

She points out that evangelical, non-denominational churches often aren't part of an overarching organisation – and "what comes along with that can be a lack of accountability".

"We can look up the safeguarding policies of larger denominations - sometimes right down to when text messaging should stop between a leader and an attendee.

"With evangelical churches the leadership can just be a family, and often it comes down to them – what they're going to report, what steps they're going to take, and for me that can be dangerous."

'Let out the poison'

Three strands of research are being carried out – into safeguarding policies; records held by faith organisations and public bodies; and survivors' stories.

Professor Tim Chapman, who is leading the project on victims' testimonies, promises a sensitive approach.

"It's very important that we hear people's authentic stories.

"We're not going in with a list of questions. We ask survivors what they want to tell us about what happened, how it's impacted their life, and what response they got if they reported it."

Survivors who take part can meet online or in person, and they can choose whether they want to speak to a man or a woman.

There is a guarantee of confidentiality, and the project team is aware some people who speak to them haven't told their families about what they've suffered.

He said there aren't adequate statistics available to put a number on how many people are affected by the issues, but he believes there are "thousands" across Northern Ireland.

"There are many who feel they can't come forward; they just can't bear talking about it.

"In my view, there's a toxicity about it. So we need to let out the poison, acknowledge what's happened, and do our best to repair it."

'Getting to the truth'

The report will form the basis of recommendations by an interdepartmental working group and a survivors' reference group to the first and deputy first ministers.

There has already been a public inquiry into abuse in residential institutions in Northern Ireland – and one is being set up into institutions for unmarried mothers.

But there has not been such an investigation into abuse by religious leaders in the community.

Tony Gribben hopes the leaders of the Northern Ireland Executive will call a public inquiry.

He highlights a number of questions in his case, which he feels need to be examined – such as whether Father Malachy Finegan was a police informer during the conflict in Northern Ireland, and how he was "packed off" to a rural parish where he was accused of continuing his abuse.

"We have too many brick walls at this point in time in terms of getting to the truth of why all this was allowed to happen over decades.

"Only a public inquiry will get to the nearest possible point of truth, which will then help survivors deal with this."

Details on how to take part in the research project are available here.

If you have been affected by the issues raised in this story, you can visit the BBC Action Line for support.