Oil giant's leaked data reveals 'awful' pollution

BBC

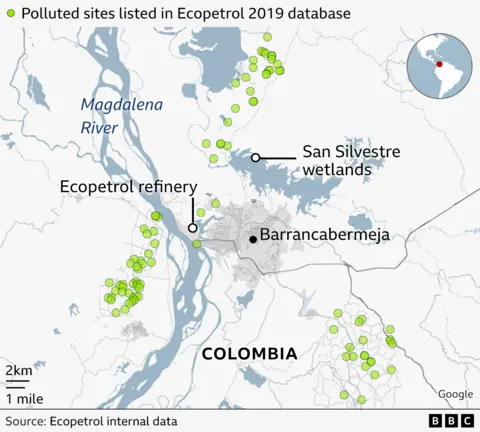

BBCColombian energy giant Ecopetrol has polluted hundreds of sites with oil, including water sources and biodiverse wetlands, the BBC World Service has found.

Data leaked by a former employee reveals more than 800 records of these sites from 1989 to 2018, and indicates the company had failed to report about a fifth of them.

The BBC has also obtained figures showing the company has spilled oil hundreds of times since then.

Ecopetrol says it complies fully with Colombian law and has industry-leading practices on sustainability.

The company's main refinery is in Barrancabermeja, 260km (162 miles) north of the Colombian capital Bogota.

The huge cluster of processing plants, industrial chimneys and storage tanks stretches for close to 2km (1.2 miles) along the banks of Colombia's longest river, the Magdalena – a water source for millions of people.

Yuly Velásquez

Yuly VelásquezMembers of the fishing community there believe oil pollution is affecting wildlife in the river.

The wider area is home to endangered river turtles, manatees and spider monkeys, and is part of a species-rich hotspot in one of the world's most biodiverse countries. Nearby wetlands include a protected habitat for jaguars.

When the BBC visited last June, families were fishing together in waterways criss-crossed by oil pipelines.

One local said some of the fish they caught released the pungent smell of crude oil as they were cooked.

In places, a film with iridescent swirls could be seen on the surface of the water - a distinctive signature of contamination by oil.

A fisherman dived down in the water and brought up a clump of vegetation caked in dark slime.

Pointing to it, Yuly Velásquez, president of Fedepesan, a federation of fishing organisations in the region, said: "This is all grease and waste that comes directly from the Ecopetrol refinery."

Ecopetrol, which is 88% owned by the Colombian state and listed on the New York Stock Exchange, rejects the fishers' claims that it is polluting the water.

In response to the BBC's questions, it says it has efficient wastewater treatment systems and effective contingency plans for oil spills.

Andrés Olarte, the whistleblower who has shared the company's data, says pollution by the firm dates back many years.

He joined Ecopetrol in 2017 and started working as an adviser to the CEO. He says he soon realised "something was wrong".

Mr Olarte says he challenged managers about what he describes as "awful" pollution data, but was rebuffed with reactions such as: "Why are you asking these questions? You're not getting what this job is about."

He left the company in 2019, and shared a large amount of company data with US-based NGO the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) and later with the BBC. The BBC has verified it came from Ecopetrol's servers.

One database he has shared, dated January 2019, contains a list of 839 so-called "unresolved environmental impacts" across Colombia.

Ecopetrol uses this term to mean areas where oil is not fully cleaned up from soil and water. The data shows that, as of 2019, some of these sites had remained polluted in this way for over a decade.

Mr Olarte alleges that the firm was trying to hide some of them from Colombian authorities, pointing to about a fifth of the records labelled "only known to Ecopetrol".

"You could see a category in the Excel where it lists which one is hidden from an authority and which one is not, which shows the process of hiding stuff from the government," says Mr Olarte.

The BBC filmed at one of the sites marked "only known to Ecopetrol", which was dated 2017 in the database. Seven years later, a thick, black, oily-looking substance with plastic containment barriers around it was visible along the edge of a section of wetland.

Ecopetrol's CEO from 2017 to 2023, Felipe Bayón, told the BBC he strongly denied suggestions that there was any policy to withhold information about pollution.

"I say to you with complete confidence that there is not, and was not any policy nor any instruction saying, 'these things can't be shared'," he said.

- If you are outside of the UK, watch Colombia: Petroleum, Pollution and Paramilitaries on YouTube

Mr Bayón blamed sabotage for many oil spills.

Colombia has a long history of armed conflict, and illegal armed groups have targeted oil facilities - but "theft" or "attack" are only mentioned for 6% of the cases listed in the database.

He also said he believed there had been a "significant advance" since then in solving problems that lead to oil pollution.

However, a separate set of data shows Ecopetrol has continued to pollute.

Figures obtained by the BBC from Colombia's environmental regulator, the Autoridad Nacional de Licencias Ambientales (Anla), show Ecopetrol has reported hundreds of oil spills per year since 2020.

Asked about the 2019 database of polluted sites, Ecopetrol admits it has records of 839 environmental incidents, but disputes that all of them were classed as "unresolved".

The firm says 95% of polluted sites that have been classed as unresolved since 2018 have now been cleaned up.

It says all pollution incidents are subject to a management process and are reported to the regulator.

The data from the regulator includes hundreds of spills in the Barrancabermeja area where Ms Velásquez and the fishers live.

The fisherwoman and her colleagues have been monitoring biodiversity in the area's wetlands, which feed into the Magdalena River.

She said there had been a "massacre" of fauna. "This year, there were three dead manatees, five dead buffalo. We found more than 10 caimans. We found turtles, capybaras, birds, thousands of dead fish," she said last June.

It is not clear what caused the deaths - the El Niño weather phenomenon and climate change may be factors.

A 2022 study by the University of Nottingham lists pollution - from oil production and other industrial and domestic sources - as one factor among several, including climate change, that are degrading the Magdalena river basin.

Mr Olarte left Ecopetrol in 2019. He moved to his family home near Barrancabermeja, and says he met with an old contact to ask about job openings. Soon afterwards, he says an anonymous caller rang his phone threatening to kill him.

"In the call I understood they thought I had put complaints against Ecopetrol, which was not the case," he says.

Mr Olarte says more threats followed, including a note that he showed to the BBC. He does not know who made the threats and there is no evidence that Ecopetrol ordered them.

Ms Velásquez and seven other people also told the BBC they had received death threats after challenging Ecopetrol.

She said an armed group had fired warning shots at her house and spray-painted the word "leave" on the wall.

The fisherwoman is now protected by armed bodyguards paid for by the government, but the threats have continued.

Asked about the threats Mr Olarte described, the former CEO Mr Bayón said they were "absolutely unacceptable".

"I want to make it totally clear… that never, at any time, was there any order of that sort," Mr Bayón said.

Ms Velásquez and Mr Olarte both know the risks are real. Colombia is the most dangerous country in the world for environmental defenders, according to the NGO Global Witness, with 79 killed in 2023.

Experts say such killings are linked to Colombia's decades-long armed conflict, in which government forces and paramilitaries allied to them have fought left-wing rebel groups.

Despite government attempts to end the conflict, armed groups and drug cartels remain active in parts of the country.

Matthew Smith, an oil analyst and financial journalist based in Colombia, says he does not believe Ecopetrol managers are involved in threats by armed groups.

But he says there is an "immense" overlap between former paramilitary groups and the private security sector.

Private security firms often employ former members of paramilitary groups and compete for lucrative contracts to protect oil facilities, he says.

Mr Olarte has shared internal Ecopetrol emails showing that in 2018, the company paid a total of $65m to more than 2,800 private security companies.

"There is always that risk of some sort of contagion between the private security companies, the types of people they employ, and their desire to continually maintain their contract," Mr Smith says.

He says this could potentially even include kidnapping or murdering community leaders or environmental defenders in order to "ensure that Ecopetrol's operations proceed smoothly".

Mr Bayón said he was "convinced that the checks and due diligence were done" regarding the company's relationships with private security companies.

Ecopetrol says it has never had relationships with illegal armed groups. It says it has a strong due diligence process and carries out human rights impact assessments for its activities.

The BBC contacted other members of Ecopetrol's former leadership from the time of Mr Olarte's employment, who strongly deny the allegations in this report.

Now living in Germany, Mr Olarte has been submitting complaints about Ecopetrol's environmental record to the Colombian authorities and the company itself - so far, without meaningful result.

He has also been in a series of legal cases against Ecopetrol and its management, related to his employment there, which are as yet unresolved.

"I did this in defence of my home, of my land, of my region, of my people," he says.

Mr Bayón stressed the economic and social importance of Ecopetrol to Colombia.

"We have 1.5 million families who don't have access to energy or who cook with firewood and coal," he said. "I believe that we must continue to rely on clean production of oil, gas, all energy sources, to transition without ending an industry that is so important for Colombians."

And Ms Velásquez remains determined to continue speaking out, despite the threats.

"If we don't go fishing, we don't eat," she said. "If we speak and report, we are killed… And if we don't report, we kill ourselves, because all these incidents of heavy pollution are destroying the environment around us."