Police unit dubbed 'authoritarian censor'

Jordan Pettitt/PA Wire

Jordan Pettitt/PA WireA national policing unit has been criticised for telling local forces to block the release of information under laws designed to safeguard the public's right to know.

The National Police Chiefs' Council (NPCC) has advised forces not to reveal information on topics including the use of banned surveillance software and the spread of super-strength drugs, the BBC has found.

Campaign group Big Brother Watch said the NPCC team – known as the central referral unit (CRU) – was acting like an "authoritarian censor" rather than a public body.

The CRU said it acted in line with legislation and only recommended how local forces should respond to Freedom of Information (FOI) requests.

The BBC was alerted to the unit's involvement in local forces' FOI responses while researching the spread of potent synthetic opioids.

Sixteen forces - more than a third of the UK's total number - had given us details about crimes linked with the drugs, but then retracted their responses at the unit's request.

The unit argued the information would undermine national security as it could be exploited by drug traffickers.

Our subsequent investigation found the CRU had advised local forces on 1,706 occasions in the first three months of 2024 - equivalent to one in every 11 requests submitted to forces in that time.

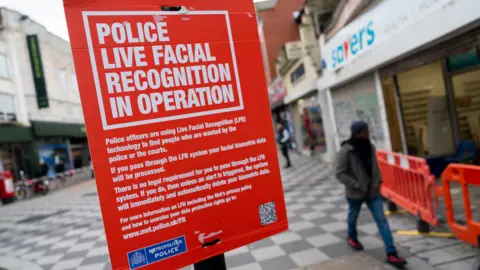

On another occasion, it cited concerns about "negative press" when advising forces to retract earlier responses and instead neither confirm nor deny if their officers had used the facial recognition search engine PimEyes, according to documents obtained by Liberty Investigates.

The software has been banned by Scotland Yard.

Jake Hurfurt

Jake HurfurtJake Hurfurt, the head of research and investigations at Big Brother Watch, said pressurising police forces to retract data was "the practice of an authoritarian censor not an accountable public body".

"It is alarming that the NPCC is going beyond giving advice to individual forces and instead seemingly orchestrating how every force responds to sensitive transparency requests," he said.

The CRU said it was legitimately discussing "negative press" or "media attention" when researching what information was already published, but those factors did not influence whether it favoured disclosure.

It also said it had had a smaller volume of work in each year since 2020.

What is Freedom of Information?

FOI laws came into force in the UK in January 2005 and allow anyone to apply to government or public bodies to see information, such as crime statistics or details on expenditure.

Using those laws, citizens can ask for information from people in power - sometimes including details they might prefer had stayed a secret.

The Freedom of Information Act presumes each request should lead to information being disclosed, unless a legal exemption applies.

Our investigation revealed the CRU did not follow the so-called "applicant-blind principle" when responding to FOI requests.

The principle states everyone should get the same level and quality of response, regardless of whether it is their first request or they use the act regularly in their work.

The CRU, however, recorded whether requesters were members of the media and their organisation.

It said it was not subject to the applicant-blind principle because it was only an advisor, but would stop the practice from March 2025.

It also said it could not share records of when it had conducted public interest tests or if and when it had favoured the disclosure of information that was in the spirit of FOI laws.

Lee Townsend

Lee TownsendAkiko Hart, director of human rights advocacy group Liberty, said: "It's incredibly concerning that police have continually tried to downplay, hide and rescind information that is in the public interest.

"At a time when public trust in police is at an all-time low, transparency in their actions has never been more important. The police have a statutory duty to provide information held by them when requested by the public and journalists, and must not try to circumvent this."

In 2022, an independent review was conducted into a separate government unit that advised other departments on their FOI responses. The review found poor practice and recommended the unit's replacement.

The so-called Clearing House was part of the Cabinet Office. It was alleged to have profiled journalists and treated their FOI requests inappropriately.

The review rejected its approach of circulating the names of requesters who had asked the same questions of several departments – a so-called round robin requester – to help it coordinate similar responses.

The government's response was to say it would pilot a new system "immediately", but the BBC found the NPCC's CRU still matched names to round robin requests 18 months after the Clearing House recommendations were published.

Oli Scarff/Getty Images

Oli Scarff/Getty ImagesClaire Miller, former data journalism editor and an expert in FOI, said further investigation was needed as the CRU did not seem to be "operating within the spirit of the FOI Act."

"It does not seem to have taken on board the criticisms of and recommendations for the Clearing House, which perhaps it should have done," she said.

The NPCC declined to give an interview but instead issued a statement.

Chief Constable Rob Carden, its digital, data and technology lead, said: "Policing is firmly committed to being open and transparent. Compliance with the Freedom of Information Act 2000 is one important way we remain accountable to the public.

"We always strive to share as much as we can in our responses with a presumption to disclose. However, there are circumstances where information cannot be disclosed and needs to be redacted, and on occasions withheld, to ensure police can continue to use tactics to protect the public or to prevent sensitive information being exploited by criminals to cause harm. These instances are strictly sanctioned with clear parameters, as set out in legislation."

He said complaints about how forces applied the FOI Act could be referred to the Information Commisioner's Office (ICO).

A spokeperson for the ICO said the data watchdog had used its powers "proactively numerous times" in the last two years to ensure police forces were compliant.

They said: "We will continue to take action when necessary, including keeping under review whether any central co-ordination in this sector is having a negative impact on compliance with the law when we examine the complaints that come to us."

Author Martin Rosenbaum, a former FOI lead for the BBC, said the performance of police forces when it came to handling FOI requests had "seriously deteriorated".

"The ICO has taken enforcement action against 15 police forces because of their FOI failings, which is more than one in three forces nationally, and is the worst record of any part of the public sector," he said.

Surrey and South Yorkshire police were among the forces issued with enforcement notices in 2024 for failing to answer requests within the 20 days set out by law.

The ICO spokesperson said there was nothing to stop public bodies like the police seeking advice from a central body on how to correctly interpret the law, but it must not stop them meeting deadlines for responses or any other FOI requirements.

Additional data journalism: Paul Bradshaw

More about this story

The Shared Data Unit makes data journalism available to news organisations across the media industry, as part of a partnership between the BBC and the News Media Association.

Read more about the Local News Partnerships here.