Starmer's stormy first year ends in crisis - now he faces a bigger battle to turn it around

BBC

BBCBy the time polls closed at 10pm on 4 July 2024, the Labour Party knew they were likely to return to government - even if they could not quite bring themselves to believe it.

For Sir Keir Starmer, reminiscing 10 months later in an interview with me, it was an "incredible moment". Instantly, he said, he was "conscious of the sense of responsibility". And yes, he confessed, a little annoyed that his landslide victory was not quite as big as Sir Tony Blair's had been in 1997.

"I'm hugely competitive," the prime minister said. "Whether it's on the football pitch, whether it is in politics or any other aspect of life."

Sir Keir watched the exit poll with a small group of advisers as well as his wife, Victoria, and his two teenaged children. Even in that moment of unsurpassable accomplishment, this deeply private prime minister was caught between the jubilation of his aides and the more complex reaction of his children, who knew their lives were about to change forever.

Looking back, the prime minister said, he would tell himself: "Don't watch it with your family - because it did have a big impact on my family, and I could see that in my children."

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesIt's important to remember how sunny the mood in the Labour Party was at that moment - because the weather then turned stormy with remarkable speed.

As the prime minister marks a year in office next week - which he will spend grappling with crises at home and abroad - British politics finds itself at an inflection point, where none of the old rules can be taken for granted.

So, why exactly was Sir Keir's political honeymoon so short-lived? And can he turn things around?

Where Sir Keir's difficulties began

Many members of the new cabinet had never been to Downing Street until they walked up to the famous black door on 5 July to be appointed. Why would they have been? The 14 turbulent years of opposition for the Labour Party meant that few had any experience of government.

This was a deficiency of which Sir Keir and his team were acutely aware.

As the leader of the opposition, he had spent significant time in 'Privy Council' - that's to say, confidential, meetings with civil servants to understand what was happening in Ukraine and the Middle East.

He also sought knowledge from the White House. Jake Sullivan, then US President Joe Biden's National Security Adviser, told me that he spoke to the future prime minister "every couple of months" to help him "make sense of what was happening".

"I shared with him our perspective on events in the Middle East, as well as in Ukraine and in other parts of the world," says Sullivan. "I thought he asked trenchant, focused, sharp questions. I thought he was on point.

"I thought he got to the heart of the matter, the larger issue of where all of these things were going and what was driving them. I was impressed with him."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDomestic preparations were not as smooth. For some, especially on the left of the Labour Party, this government's difficulties began with an over-cautious election campaign.

Sharon Graham, the general secretary of the trade union Unite, told me that "everyday people [were] looking for change with a big C. They were not looking for managerialism".

It's a criticism with which Pat McFadden, a senior cabinet minister, having run the campaign, is wearily familiar. "We had tried other strategies to varying degrees in 2015, 2017, 2019, many other campaigns previously - and they'd lost.

"I had one job. To win."

Breaking away from Corbynism

Having made his name as a prominent member of Jeremy Corbyn's shadow cabinet, Sir Keir won the party leadership in 2020 offering Labour members a kind of Corbynism without Corbyn.

But before long he broke decisively with his predecessor.

In the campaign this meant not a long list of promises, but a careful approach. Reassurance was the order of the day: at the campaign's heart, a focus on what Labour wouldn't do: no increase in income tax, national insurance or VAT.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesYet a big part of preparing for government was not just the question of what this government would do, but how it would drive the government system.

For that, Sir Keir turned to Sue Gray.

Having led the Partygate investigation into Boris Johnson, Gray was already unusually high-profile for an impartial civil servant. Her close colleagues were stunned when in 2023 she agreed to take up a party political role as Sir Keir's chief of staff.

"It was a source of enormous controversy within the civil service," says Simon Case, who until a few months ago as cabinet secretary was head of the civil service.

Sue Gray's task was to use her decades of experience of the Whitehall machine to bring order to Sir Keir's longstanding team.

She started work in September 2023, and the grumblings about her work began to reach me weeks, or perhaps even days, later. Those in the team she joined had expected her to bring organisational clarity.

Tensions came when she involved herself in political questions too.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGray also deliberately re-prioritised the voices of elected politicians in the shadow cabinet over unelected advisers.

Questions about what exactly her role should be were never quite resolved, in part because Rishi Sunak called the general election sooner than Labour had expected.

Gray spent the campaign in a separate office from the main team, working with a small group on plans for the early days in government. Yet those back in Labour HQ fretted that, from what little they gleaned, that work was inadequate.

A few days before the election those rumours reached me. I WhatsApped a confidant of Sir Keir to ask what they had heard of the preparation for government.

"Don't ask," came the reply. "I am too worried to discuss it."

A lack of decisive direction

What is unquestionable is that any prime minister would have struggled with the backdrop Sir Keir inherited.

Simon Case described to me how, on 5 July just after Sir Keir had made his first speech on the steps of No 10, he had thwacked a sleepless new prime minister with "the heavy mallet of reality".

"I don't think there are many incoming prime ministers who'd faced such challenging circumstances," he said, referring to both the country's economic situation and wars around the world.

The King's Speech on 17 July unveiled a substantial programme, making good on manifesto promises: rail nationalisation, planning reform, clean energy investment. But those hoping for a rabbit out of the hat, a defining surprise, were disappointed.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn so many crucial areas — social care, child poverty, industrial strategy — the government's instinct was to launch reviews and consultations, rather than to declare a decisive direction.

As cabinet secretary, Case could see what was happening — or not happening — across the whole of government. "There were some elements where not enough thinking had been done," he said.

"There were areas where, sitting in the centre of government, early in a new regime, the prime minister and his team, including me as his sort of core team, knew what we wanted to do, but we weren't communicating that effectively across all of government."

Not just communication within government: for us journalists there were days in that early period where it was utterly unclear what this new government wanted its story to be.

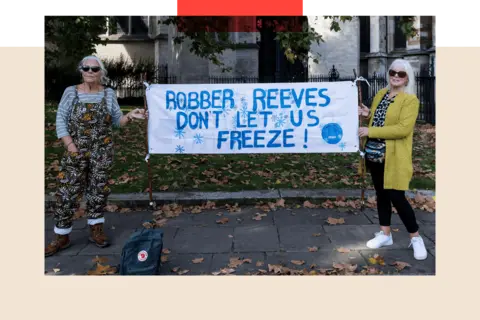

That made those early announcements, which did come, stand out even more: none more so than Chancellor Rachel Reeves's announcement on 29 July that she would means-test the winter fuel payment.

It came in a speech primarily about the government's parlous economic inheritance. That is not what it is remembered for.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSome in government admit that they expected a positive response to Reeves's radical frankness about what the government could and could not afford to do. Yet it sat in isolation - a symbol of this new government's economic priorities, with the Budget still three months away.

Louise Haigh, then the transport secretary, remembered: "It came so early and it hung on its own as such a defining policy for so long that in so many voters' minds now, that is the first thing they think about when they think about this Labour government and what it wants to do and the kinds of decisions it wants to make."

The policy lasted precisely one winter. Sir Keir and his chancellor have argued in recent weeks that they were able to change course because of a stabilising economy.

McFadden was more direct about the U-turn. "If I'm being honest, I think the reaction to it since the decision was announced was probably stronger than we thought," he admits.

'Two-tier Keir' and his first UK crisis

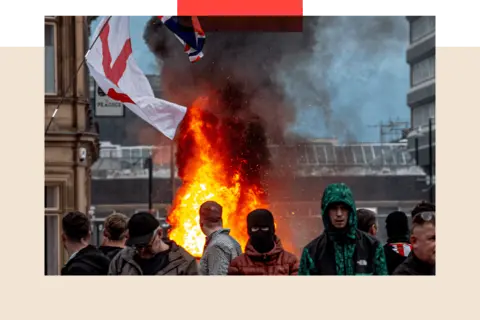

At the same time the chancellor stood up to announce the winter fuel cuts, news was unfolding of a horrific attack in Southport.

Misinformation about who had carried out the attack fuelled the first mass riots in this country since 2011, when Sir Keir had been the director of public prosecutions. Given the nature of the crisis, the prime minister was well placed to respond.

"As a first crisis, it was dealing with a bit of the machinery of government that he instinctively understood - policing, courts, prisons," Case says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSir Keir's response was practical and pragmatic — making the judicial system flow faster meant that by mid-August at least 200 rioters had already been sentenced, most jailed with an average term of two years.

But in a way that was not quite clear at the time, the riots spawned what has become one of the defining attacks on the prime minister from the right: that of 'two-tier Keir'.

The idea that some rioters were treated more harshly than other kinds of protesters had been morphed over time into a broader accusation about who and what the prime minister stood for.

Sir Keir had cancelled his family holiday to deal with the riots. Exhausted, he ended the summer dealing with questions about his personal integrity in what became known as 'freebiegate'.

Most of the gifts for which he was being criticised - clothing, glasses, concert tickets - had been accepted before the election but Sir Keir was prime minister now. Case told me there was a "naivety" about the greater scrutiny that came with leading the country.

Perhaps more than that, there was a naivety in No 10 about how Sir Keir was seen. Here was a man elected in large part because of a crisis of trust in politics. He had presented himself as different.

Telling voters that he had followed the rules was to miss the point — they thought the rules themselves were bust.

The political price of 'dispensing with' Gray

By the winter of 2024, the sense of a government failing to get a grip of itself or a handle on the public mood, had grown. A chorus of off-the-record criticism, much of it strikingly personal, threatened to overwhelm the government.

There were personal ambitions and tensions at play, but more and more insiders - some of them fans of Gray initially - were telling me that the way in which Sir Keir's chief of staff was running government was structurally flawed, with the system simply not working properly.

Gray announced in early October that she had resigned because she risked becoming a "distraction". In reality, Sir Keir had sacked her after some of his closest aides warned him he risked a mutiny if he did not.

Sue Gray was approached both for an interview and for her response to her critics but declined.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTo the end she retained some supporters in the cabinet including Louise Haigh. "I felt desperately sorry for her," she says.

"It was just a really, really cruel way to treat someone who'd already been so traduced by the Tories - and then [was] traduced by our side as well."

Sir Keir appointed Gray. He empowered Gray. And he dispensed with Gray. This was the prime minister correcting his own mistakes - an episode which came at a high political price.

A bridge on the world stage

Yet on the world stage the prime minister continued to thrive, winning praise across political divides in the UK and abroad.

Jake Sullivan, Biden's adviser, was impressed by Sir Keir's handling of US President Donald Trump, describing the Oval Office meeting where the prime minister brandished an invitation from the King as "the best I've seen in terms of a leader in these early weeks going to sit down with the current president".

It's an irony that it is Sir Keir, who made his reputation trying to thwart Brexit, who has found for the UK its most defined diplomatic role of the post-Brexit era — close to the US, closer than before to Europe, at the fore of the pro-Ukraine alliance, striking trade deals with India and others.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd it has provided him with something more elusive too: a story — a narrative of a confident, pragmatic leader stepping up on the world stage, acting as a bridge between other countries in fraught times.

The risk, brought into sharp relief during the Israel-Iran conflict in recent days, is that Trump is too unpredictable for such a role to be a stable one.

The international arena has sharpened Sir Keir's choices domestically as well. Even while making welfare cuts that have displeased so many in his party, the prime minister has a clearer and more joined-up argument about prioritising security in all its forms: through work, through economic prudence, through defence of the realm.

And yet, for plenty of voters Sir Keir has found definition to his government's direction too late. Labour's poor performance last month in the local elections plus defeat at the Runcorn and Helsby by-election were a blow to Sir Keir and his team.

Reuters

ReutersIt's far from unheard of for a governing party to lose a by-election, but to lose it to Reform UK on the same night that Nigel Farage's party hoovered up councils across England made this a distinctively new political moment.

Two days afterwards, Paul Ovenden, Sir Keir's strategy director, circulated a memo to Downing Street aides, which I've obtained.

It called for a "relentless focus on the new centre ground in British politics".

The crucial swing voters, Ovenden wrote, "are the middle-age, working class, economically squeezed voters that we persuaded in the 2024 election campaign. Many of them voted for us in 2024 thinking we would fix the cost of living, fix the NHS, and reduce migration… we need to become more ruthless in pursuing those outcomes".

For more than 100 of Starmer's own MPs, including many of those elected for the first time in that landslide a year ago, the main priority was ruthlessly dismantling the government's welfare reforms - plunging the prime minister as he approaches his first anniversary into his gravest political crisis yet.

The stakes were beyond high. For the prime minister to have backed down to avoid defeat on this so soon after the winter fuel reversal raises questions about his ability to get his way on plenty else besides.

So, if this first year has done anything, it has clarified the stakes.

This is not just a prime minister and a Labour Party hoping to win a second term. They are trying to prove to a tetchy and volatile country that not only do they get their frustration with politics, but that they can fix it too. None of that will be possible when profound policy disagreements are on public display.

Top picture credit: PA and Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

Sign up for our Politics Essential newsletter to read top political analysis, gain insight from across the UK and stay up to speed with the big moments. It'll be delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.