Patients stuck in hospital over legal issues

BBC

BBCA third of patients who are delayed getting out of hospital in Scotland's largest health board area are stuck because of a legal complication.

Prof Angela Wallace, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde's nurse director, says significant delays can come from patients not having power of attorney in place to approve their care plans.

This is a legal way to give somebody you trust the power to make financial and welfare decisions on your behalf.

If patients come to hospital after an illness and no longer have capacity to make decisions for themselves, it can lead to significant delays when they are ready to be discharged.

The current system means that a guardianship order has to be put in place - but it has to go through the courts and that can take many months.

Hospitals across Scotland are working at capacity.

Bed shortages on wards means patients are cared for in corridors, waiting too long in A&E or finding that a long-awaited operation is cancelled.

But each day, an average of 2,000 people are unable to get out of hospital despite being medically fit to be discharged.

There are many reasons why people are getting stuck in hospital, ranging from a lack of social care workers to a shortage of spaces in care homes.

But Prof Wallace said one of the biggest reasons for patients being delayed in their discharge was down to not having the right legal documents in place.

She says that across her health board right now there are 300 patients unable to get out of hospital despite not needing to be there.

In a third of those cases, it is because people do not have a power of attorney in place.

No-one has the automatic right to make decisions on your behalf.

Organising a power of attorney means if you cannot make the decision for yourself, someone you trust can make choices about your care - such as if you should receive healthcare treatment or where you should live.

Prof Wallace says that families can sometimes be reluctant to discuss their future wishes because it can feel it is about coming to the end of life, but she says it allows a patient's wishes to be absolutely clear.

"If patients have a power of attorney in place then we are absolutely clear about their wishes," Prof Wallace says.

"Therefore we can facilitate their discharge from hospital to a place of care that they have decided on before they have become unwell."

Prof Wallace says she has seen patients delayed more than 400 days in an acute hospital due to legal complications.

"It is not good for them, they feel isolated, and they become deconditioned and start to lose their mobility," she says.

Christine Carmichael, whose 67-year-old husband Norman had a stroke in January, says her advice is to get the legal side arranged as soon as you can.

The couple, who are recently retired, had just returned from a holiday in Portugal when Norman collapsed in their kitchen.

Not having power of attorney sorted has already caused the family financial issues and it could have implications for Norman's future care.

"We always spoke about it, but never got round to it. You never think it's going to happen to you but it shouldn't be left," says Christine.

"People think it's an age thing but it's something you can do as soon as you are married."

Norman currently has some mobility and speech issues, but it is hoped he will be able to get out of hospital and continue rehabilitation at home.

On the day we visited, the Royal Alexandra Hospital (RAH) in Paisley was full.

There was no room on the stroke ward where Norman was being cared for to admit a further four patients who needed to be in the ward.

One of those patients was still in the Emergency Department, which was operating at double its usual capacity.

During winter it was routinely four times its capacity.

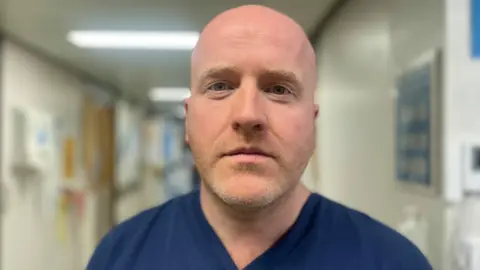

Dr Chris McDonald, the clinical director for emergency medicine at the RAH and at Inverclyde hospital, says this winter is the worst he has seen.

His department has routinely been operating at 400% capacity.

"It's been incredibly difficult, I think we have all felt the strain," he said.

"We are walking down corridors that are completely full of patients and people are asking us for help and you've not got no time."

He says the single biggest challenge they face is getting patients onto the wards for further care.

Prof Wallace says: "Every single day we could do better in terms of getting people both in and out of hospital.

"Across our sites, I think we are close to 100% occupancy. We don't want to care for patients in areas they shouldn't be cared for, it's not ideal."

Modifying the law

The Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (RCPE) is calling on the Scottish government to introduce legislative reform around power of attorney and guardianship provisions, with funding attached to make it easier for people to put in place.

Dr Conor Maguire, vice president (international) at RCPE, says it can lead to elderly patients or those with dementia spending up to half their remaining lives in a hospital bed which is unsuitable and disruptive.

"The government should move forward with modifying the law around guardianship provisions so that patients who lack capacity to make decisions about their care can be moved from an NHS healthcare environment to an appropriate social care environment without delay – ideally to the nursing or care home in which they are to reside indefinitely - while they wait for the outcome of the court process," he said.

The Scottish government it had published analysis last month of responses to a consultation on proposals for reform of the Adults with Incapacity Act, including powers of attorney and guardianship orders.

A spokesperson said: "We are now considering those responses and working towards modernising the AWI Act, taking forward recommendations from the Scottish Mental Health Law Review."