'I clean up the aftermath of traumatic deaths'

BBC

BBCWarning: The following article contains upsetting content

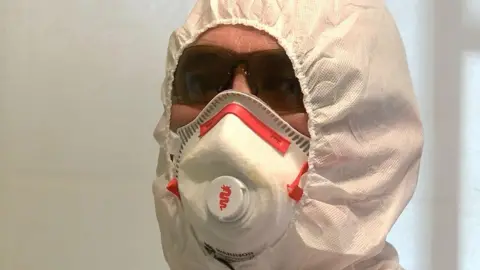

"The flies and the smell are the worst things," says Jim Gildea through a face mask, as he sprays disinfectant on the floor of a room where a man died weeks earlier.

Jim, from Gosport, Hampshire, recalls his first trauma cleaning job was decontaminating a building after a murder in Portsmouth, going in after scenes of crime officers had finished their work and the victim's body had been removed.

"You never get used to it," he says. "It's the most unpleasant thing you could possibly ever think of doing and it's different every time."

With 10 years' experience behind him, Jim has developed coping mechanisms to protect himself from the emotional challenges this type of work can bring.

He says he always treats the scene of a death with "respect", while at the same time trying to "forget the reality" of what he is doing.

"I find I'm only able to do this by switching off completely," he says.

The smell in the room is overwhelming.

"We use concentrated odour blocks, break them up, put them around the house and rub them on the nostril of the mask by the side of the filter and that really covers it up," Jim says.

Along with a colleague, he works methodically, sanitising the room with a fogging machine, cutting away carpet and carefully packing all contaminated materials into sealed boxes to be taken to an incinerator.

Body fluids on the floor are covered with absorbent granules, as Jim explains how human bodies decompose at different rates in different environments, temperatures and humidity.

"You've got to make sure your protocols are right," he says. "Your chemicals are right and yourself and your staff are safe.

"Then it's scrapers, bags and strong stomachs, and you just get it done."

The hundreds of dead flies on the floor were dealt with on Jim's first visit here.

Some species can detect decomposing tissue from up to 10 miles away.

He says: "Sometimes it can be like a scene out of The Exorcist, where you can hear the throb of the flies circling before you put your hand on the door handle and when you open it they rush to escape."

While he tries to avoid knowing too much about the intricate details of the human stories behind each death, he has come to learn that people can experience profound loneliness, even when living with others.

He recalls being called to a house which was home to a landlord with four tenants, after a putrid smell had caused them to discover one of the tenants had died over the Christmas holidays.

"The sad thing is that no one had knocked on his door on Christmas day and he was dead and he'd been there for six-and-a-half days," he said.

The tenant had been a single man, which Jim says is often the case.

He estimated at least nine out of every 10 of his trauma cleaning jobs followed the sudden, unexpected or unattended deaths of men.

This anecdotal evidence aligns with research which reveals men are three times more likely than women to need a state-funded funeral after dying alone, in poverty or without family who can afford a cremation or burial.

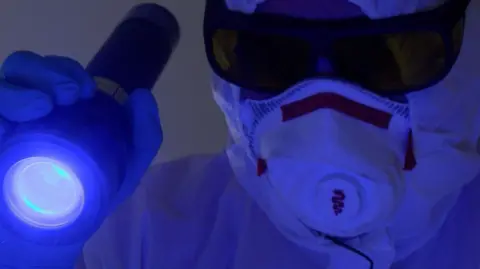

Having finished what he calls a "rough clean", he puts yellow tinted lenses over his protective glasses and switches on a forensic investigator's torch so he can see how much contaminated matter remains.

He looks pleased and says: "You can really see it on those floor tiles, because underneath they're glowing red, aren't they?

"We'll be able to get them absolutely perfect with this equipment and make sure we've removed every single biological trace."

Despite the grim nature of his work, clearly Jim finds a quiet fulfilment in meticulously erasing all evidence of trauma, so others do not have to face it.

With a wry smile, he tells me: "I'll be doing this until the day I die, until I'm a mess on the floor somewhere."

You can follow BBC Hampshire & Isle of Wight on Facebook, X, or Instagram.