'Hotbed of rave culture' - East Anglia in the '90s

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIf glow sticks and "techno, techno, techno" mean anything to you, perhaps you lived the '90s rave culture - and if you did, an author is hoping to document your memories.

Music journalist Matt Anniss says Cambridgeshire, Norfolk and Suffolk were a "hotbed" of the rave scene back in the day.

He is planning to put together a "people's history" of the genre from the late 1980s and '90s - and beyond.

Raves can be controversial, with unlicensed and illegal events causing disruption to residents and landowners, but he is keen to hear stories about the "countercultural playground for ravers".

Mariam Issimdar/BBC

Mariam Issimdar/BBC"A few years ago I wrote a book called Join the Future... which looked at what we call the hidden history [of the rave scene and British bass music]," Mr Anniss says.

"I started looking at things that happened in different parts of the country and what was missing from the archive.

"One of the biggest things that's missing in terms of British dance music is what happened in predominantly rural regions like East Anglia.

"Obviously there was a dance music scene with clubs and record shops, but what drew people from the region together were the raves and free parties."

Holly Mabee/courtesy of Louise Render

Holly Mabee/courtesy of Louise RenderAnniss, 46, from Bristol, has strong family ties to eastern England, particularly Norfolk, and is researching the region's rave history for a PhD at Southampton Solent University.

His work will cover a 30-year period "to see how things changed and whether rave culture has become embedded in counties like Cambridgeshire, Norfolk and Suffolk".

"The earliest raves or free parties in Cambridgeshire actually took place before rave, from an outfit called the Tonka Sound System, who used to break into abandoned buildings in Cambridge and put on parties from 1985 onwards," he says.

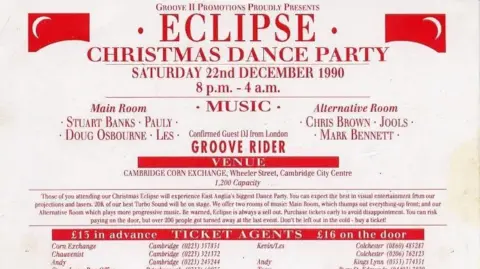

"Then there were other warehouse parties run by the Banks Brothers who also ran a rave at the Cambridge Corn Exchange called Eclipse."

He says at one point there was so much going on that Cambridgeshire Police even had its own "rave-busting party unit" - although the force was unable to comment on that.

Getty Images

Getty Images Getty Images

Getty ImagesMeanwhile, in Norfolk, "there was dance music culture in most of the larger towns - Great Yarmouth, Norwich, King's Lynn - but also smaller club nights in places like Cromer and Sheringham", he says.

"But later, what became bigger were things like illegal raves and especially in places such as Thetford Forest."

Because of legislation, that activity largely died off in other parts of the UK, he says, but not so in East Anglia.

"I think there are several things in play here. One, there's something in the character of the people in East Anglia - a long history of non-conformity - and there's a lot of space and not a lot of nightclubs."

Chris Brown

Chris BrownNick Slater, 57, is still part of Shades of Rhythm - a DJ outfit that regularly played on the rave scene in the Peterborough area in the '90s.

"Things were really local back then, so each town would have a couple of people who were in the loop and in most towns you'd have a bar or some place where everybody could meet," he recalls.

Shades of Rhythm

Shades of Rhythm"[Rave] was a new genre, it wasn't like anybody had done this before.

"It was derived probably from funk and soul and disco and then obviously rap music, electro disco, break dance, and it led us to a clashing technology where 'sample' all of a sudden came out, and we could start to sample drumbeats from rap records and we'd have to speed them up.

"We were using technology to the full advantage, which almost led to things speeding up and becoming dance music - rave music as we know it."

Shades of Rhythm

Shades of RhythmAsked about his happiest memories of the time, he says: "It's just the people you met - everybody was like-minded - it felt like something big was about to happen and you felt part of it.

"It was just brand new."

Chris Brown

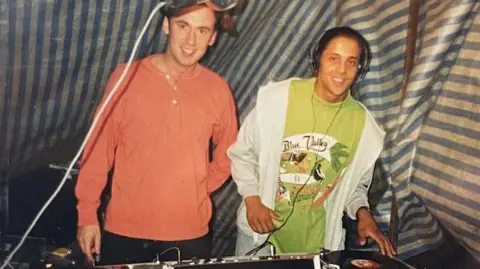

Chris BrownChris "Charlie" Brown also used to DJ at raves in the Cambridge area.

Now 62, he still plays events and says the scene remains strong, "although now legally".

"I remember we did a gig in the Beechwoods [nature reserve] just outside Cherry Hinton and we had someone at [another venue] on one of those big Nokia mobile phones - like a brick - then we made the phone call asking them to announce where the gig was."

Chris Brown

Chris BrownHe says: "About 10 minutes later we saw hundreds of headlights coming up the Gogs [Gog Magog Hills]."

Although the police arrived it was very good natured, he says, and the party was wound up in the early hours.

About 350 people attended and when it finished, many went around collecting rubbish.

"When we left the site it was like nothing had ever happened."

Norfolk Police

Norfolk PoliceWhile Anniss accepts raves can cause disruption, he says his PhD research will not actively focus on landowners or police involvement as "disruption is quite well covered within the archives by newspapers".

"What interests me is obviously the events that happened - how and why they happened - why there were more raves in Cambridgeshire and the rest of East Anglia than in some other parts of the country," he says.

"And not every rave was illegal. Sometimes farm or landowners were paid by rave promoters.

"What you tend to find when you try to document history like this through people is that some have great memories - really vividly - and others don't.

"Obviously the elephant in the room is the associated drug culture. That is part of it. I'm not interested in asking people 'did they take drugs'... that's not why I'm doing it."

His anonymous online survey, which will form the basis of the "people's history", asks about "Your East Anglian Rave Journey" and most memorable events.

Follow Cambridgeshire news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, Instagram and X.