The Welsh explorer who put Canada on the map

Getty Images

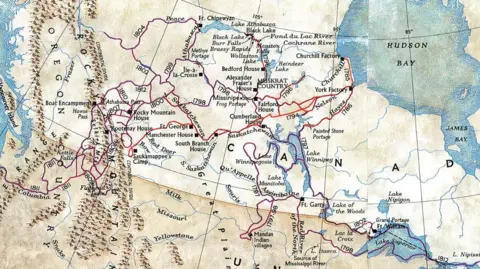

Getty ImagesDonald Trump's suggestion Canada becomes the 51st state has brought into the spotlight international boundaries that have remained firm since a Welshman plotted them more than 200 years ago.

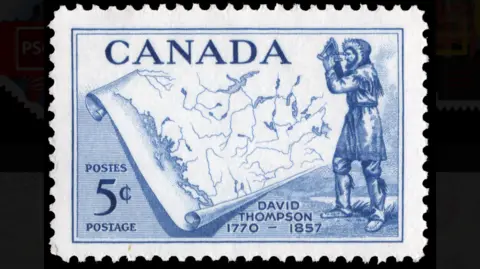

Born in 1770, Dafydd ap Thomas, or David Thompson as he was better known, surveyed and mapped more than four million square miles of the country's interior.

He escaped poverty, and despite being partially blind and having a permanent limp from a badly broken leg, he used the stars to plot latitude and longitude.

His achievements include being the first westerner to navigate the Columbia River from its source to the Pacific Ocean, and charting the border between Canada and the US.

His international boundary remains firm to this day, with Canadians furiously rejecting US President Trump's suggestion that their country abandons it and becomes the US' "51st state".

"Throughout the 1810s and early 1820s, Thompson charted every inch of the disputed boundary, zig-zagging between the Great Lakes and noting the landmarks and river flow all the way along to within a mile or so's accuracy," said biographer D'Arcy Jenish.

"His maps are still the basis of the modern-day boundary, something which Donald Trump would probably rather forget."

Thompson fostered close relations with several Native American nations in his work, and became known as Koo-Koo-Sint - or Stargazer.

He also campaigned for the rights of First Nation people, and married a Cree woman, Charlotte, their 57-year marriage the longest recorded in Canada at the time.

University of Toronto

University of TorontoThompson's parents moved to London from Radnorshire shortly before his birth, where they adopted the anglicised Thompson rather than ap Thomas.

Around his second birthday, his father died suddenly, leaving a wife and two children with no means of supporting themselves.

Aged seven, Thompson was enrolled in Westminster Grey Coat Hospital - a school for promising disadvantaged children.

It was there he discovered a love of mathematics.

Today, it is a girls academy, and archivist Penny Swan said it was set up by local tradesmen with children at heart.

But when Thompson arrived in 1777, the matron was a "dreadful human being" called Mrs Thoms.

"She stole the children's food rations and sold them on, as well as administering dreadful beatings," she added.

Mrs Swan found documents showing pupils smashed windows and started fires to get expelled and escape floggings, semi-starvation and cruelty.

Ontario Government Archives

Ontario Government ArchivesNevertheless, Thompson thrived, writing of his love for novels such as Gulliver's Travels.

His 1916 biographer J B Tyrrell commented: "His early handwriting is beautifully distinct and regular, and his spelling is remarkably good for the time and circumstances in which he lived."

He excelled to such an extent that by 14 he secured a seven-year apprenticeship, working on fur-trapping ventures into Canada.

But by the late 1780s, he lost the sight in his right eye after an infection, and suffered a life-threatening leg break.

D'Arcy Jenish

D'Arcy JenishD'Arcy Jenish wrote the 2003 account of Thompson's life, Epic Wanderer, and said: "He suffered a horrible injury in a sledging accident.

"I believe he broke his femur, and they didn't think he'd live.

"It took him a year to get over that, and even then he'd walk with a pronounced limp for the rest of his life."

But in that year, he met Peter Fidler, a surveyor, who got Thompson hooked on celestial navigation - using the sun and stars to determine locations.

This helped Thompson make a connection with native people, as they also revered the stars.

While the native people were searching the sky for tales of ancestors, Thompson was pinpointing latitude and longitude.

It was customary for graduates to be awarded two new suits and a cash sum.

But when Thompson completed his apprenticeship in 1792, he asked for a sextant, telescope and other navigational equipment instead.

Mr Jenish said: "He was a man in high demand, not only because of his navigational skills, but also his mastery of several native languages, and his ability to forge working relationships."

He described him as a genius, saying his plotting of Canada's notoriously complex waterways were accurate to within a mile, despite the lack of depth perception he experienced through sight loss.

By the 1810s, he had discovered a trading route through the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific via the previously uncharted Columbia River.

David Thompson Country

David Thompson CountryBy 1812, he planned on returning to a desk job in Montreal, with wife Charlotte and their growing family.

Yet, Thompson's plans for a quiet retirement were curtailed after the end of the 1812 British-American War.

This brought about a need for the border between Canada and the US to be settled once and for all.

Mr Jenish said there was only one man for the job - and the accuracy of Thompson's work meant it was accepted by both sides.

Thompson family photo

Thompson family photo"They were their own people, like they were voyagers," Luke Thompson said of his seven-times great grandparents.

He said the family are "massively proud" of their achievements, adding: "The fact that they called David Koo-Koo-Sint tells you all you need to know about how much they were accepting of each other's cultures.

"Out there back then, there was no civilisation really, like no cities, no nothing around.

"So sometimes you had to rely on each other to survive."

Luke Thompson

Luke ThompsonIn the 1820s, Thompson retired a relatively wealthy man.

But bad investments, bad luck and resentment from some Canadians who felt short-changed by the unswerving fairness of his boundary survey saw him become poor.

In his old age, he was forced back to work.

This saw him map out streets in Canada's growing towns.

He died in Montreal in February 1857, aged 86, shortly before his wife.

Their marriage of 57 years and nine months was the longest recorded in Canadian history at the time.

Mr Jenish said: "Charlotte was by his side for 58 years from when they met in 1799 until his death in 1857.

"Not left back home, but on his adventures, supporting him with practical skills and local knowledge in an inhospitable landscape, and sharing in his achievements."

Grey Coat Hospital Foundation

Grey Coat Hospital Foundation Canada Post

Canada Post