'Our mosque was threatened after the 7/7 bombings'

BBC

BBCOn 7 July 2005, a series of explosions on London's public transport system killed 52 people and injured more than 770.

The actions of the bombers, all British Muslims, affected Muslim communities - both immediately and in the long term.

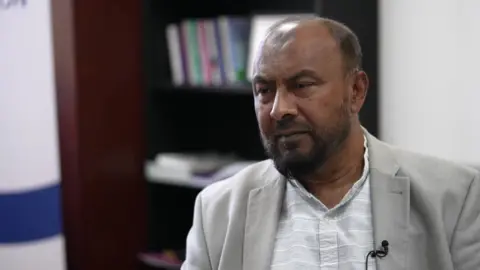

Dilowar Khan, then an executive director at East London Mosque, described "a very tense time for all of us". He said the community felt anti-Muslim hatred, with women in particular afraid to leave their homes; that the mosque received "a number of bomb threats", and its windows were smashed.

Another incident involved "a good number of men who came down and urinated in front of the main entrance".

Although the mosque publicly condemned the attacks, Mr Khan said many Muslims in the community faced increased scrutiny, suspicion and hostility.

"Shortly after the incident, we received a couple of bomb threats," he said. "I remember it was two Fridays actually. Friday is the busiest day for the mosque and so we had to call the police.

"We also received white powder by post, and again we had to call the police.

“Fortunately, it wasn't anthrax."

He said many Muslim women were "afraid to go on the bus and the underground" even though one of the congregation of his mosque, a young woman in her 20s, was killed in the bombing.

"Women's hijabs were pulled, they were spat on.

"I remember one incident where a woman was refused entry on the bus. The bus driver, he was probably Islamophobic or racist.

"My own sisters, my wife, they felt very scared to go out."

'Alienated and attacked'

Shahmina, a pharmacist, was just a teenager when the bombings took place.

"I was 13. And all of a sudden I started feeling quite alienated," she said. "Suddenly my faith felt like something that could be attacked.

"We felt afraid to openly be Muslim.

"We would avoid certain areas if we knew there wouldn’t be a huge amount of Muslims there, because then we felt isolated.

"It was like you could become a prime target for Islamophobia and racism.

"It became rife after these attacks because what we were seeing in the media was a depiction that these attacks were central to being a Muslim and being Islamic and it wasn't - these attacks were isolated to individuals."

Two decades on, London's Muslim community has more than doubled to 1.3m people, but for Shahmina, it is still difficult.

"I'm feeling it coming back again with the resurgence of what's happening in the international political sphere," she said.

"I think relations can improve if we start changing the language we use around Muslims and people of different ethnic groups.

"If we shift how we talk about them when a crime is committed, we may find that actually the general public will have a different view on our community."

At the East london Mosque, community leaders regularly hold interfaith events and open days in the hopes of promoting a better understanding between people of different faiths.

Imam Shaqib Juneja is a former teacher and now works with a Muslim youth group.

"We don't want people to feel that we're different," he said.

"That's an important point, because one of the things that happened after 7/7 was a lot of the talk that was happening from politicians, from the media, about the portrayal of Muslims, perhaps even on the BBC - it made Muslims feel we are different.

"It's not the community that has the problem, it's a few individuals.

"But when it's portrayed as the community having the problem, people start to feel there is a lack of trust.

"We're people just like everybody else. We're human beings. There are more things that we have in common than actually make us different."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected]