Why Trump is hitting China on trade - and what might happen next

Suddenly, Donald Trump's trade war is in much sharper focus.

Rather than a fight on all fronts against the world, this now looks far more like a fight on familiar Trumpian territory: America v China.

The 90-day pause on the higher "retaliatory" tariffs levied on dozens of countries still leaves a universal across-the-board tariff of 10% in place.

But China – which ships everything from iPhones to children's toys and accounts for around 14% of all US imports – has been singled out for much harsher treatment with an eye-watering rate of 125%.

Trump said the increase was due to Beijing's readiness to retaliate with its own 84% levy on US goods, a move the president described as showing a "lack of respect".

But for a politician who first fought his way to the White House on the back of an anti-China message, there is much more to this than simple retaliation.

For Trump, this is about the unfinished business of that first term in office.

"We didn't have the time to do the right thing, which we're doing now," he told reporters.

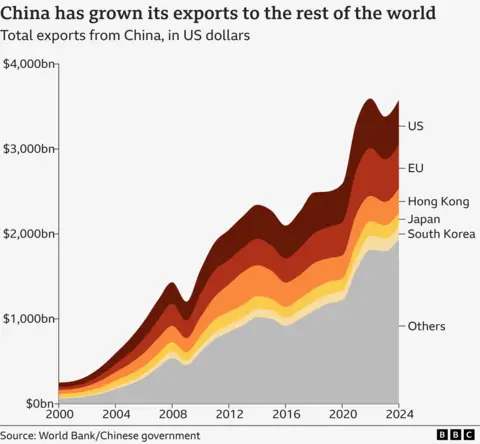

The aim is nothing less than the upending of an established system of global trade centred on China as the factory of the world, as well as the once widely held view that underpinned it – the idea that more of this trade was, in and of itself, a good thing.

Reuters

ReutersTo understand just how central this is to the US president's thinking, you need to go back to the time before anyone ever thought of him as a possible candidate for office, let alone a likely winner.

In 2012, when I first reported from Shanghai - China's business capital - increased trade with the country was seen by almost everyone – global business leaders, Chinese officials, visiting foreign governments and trade delegations, foreign correspondents and learned economists – as a no brainer.

It was boosting global growth, providing an endless supply of cheap goods, enriching China's army of new factory workers increasingly embedded in global supply chains, and providing lucrative opportunities to multinational corporations selling their wares to its newly minted middle classes.

Within a few of years of my arrival, China had surpassed the US to become the world's biggest market for Rolls Royce, General Motors and Volkswagen.

- What are tariffs and why is Trump using them?

- US pauses higher tariffs for most countries but hits China harder

- Trump steps back from cliff edge of all-out global trade war

There was a deeper justification, too.

As China got richer, so the theory went, Chinese people would begin to demand political reform.

Their spending habits would also help China transition to a consumer society.

But the first of those aspirations never happened, with China's ruling Communist Party only tightening its grip on power.

And the second one didn't happen fast enough, with China not only still dependent on exports, but openly planning to become ever more dominant.

Its infamous policy blueprint - published in 2015 and entitled Made in China 2025 - set out a huge state-backed vision of becoming a global leader in a number of key manufacturing sectors, from aerospace to ship building to electric vehicles.

And so it was that same year, a political outsider launched his run for US president, making the case repeatedly on the campaign trail that China's rise had hollowed out the American economy, driven Rust Belt decline and cost blue-collar workers their livelihoods and dignity.

Trump's first-term trade war broke the mould and shattered the consensus. His successor, President Joe Biden, kept much of his tariffs on China in place.

And yet, even though they have undoubtedly caused China some pain, they have not done much to change the economic model.

China now produces 60% of the world's electric cars – a large proportion of them made by its own homegrown brands - and 80% of the batteries that power them.

So, now Trump is back, with this tit-for-tat escalation on levies.

It would, arguably, be the biggest shock ever delivered to the established global trading system, were it not for all the other on-again off-again tariff measures the US president has rolled out in recent days.

What happens next depends on two key questions.

Firstly, whether China takes up that offer to negotiate.

And secondly, assuming it eventually does, whether China is willing to make the kind of major concessions that America is looking for, including a complete overhaul of its export driven economic model.

In answering them, the first thing to say is that we are in completely uncharted territory, so we should be wary of anyone who says they know how Beijing is likely to react.

But there are certainly reasons to be cautious.

China's vision of its economic strength - one based on strong exports and a tightly protected domestic market - is now closely bound up with its idea of national rejuvenation and the supremacy of its one-party system.

Its tight control over the information sphere means it will be unlikely to drop its barriers to American technology companies, for example.

But there is a third question, and it is one for America to answer.

Does the US still believe in free trade? Donald Trump often suggests that tariffs are a good thing, not merely as a means to an end, but as an end in themselves.

He talks about the benefit of a protectionist barrier for America, in order to stimulate domestic investment, encourage American companies to bring those foreign supply chains back home, and raise tax revenues.

And if Beijing believes that is indeed the primary purpose of the tariffs, it may decide there is nothing to negotiate anyway.

Rather than championing the idea of economic co-operation, the world's two biggest superpowers may find themselves locked in a fight for winner-takes-all economic supremacy.

If so, that really would mark a shattering of the old consensus, and a very different, possibly very dangerous, future.