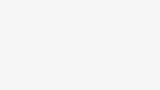

'We want our kids to know their Polish heritage'

Submitted

SubmittedA Saturday school in Northamptonshire aims to teach children about their Polish heritage and language. But many of its pupils - and teachers - have returned to Poland since Brexit. Where does that leave the school and the local Polish community?

Wellingborough Polish School launched in 2006 with just 40 pupils.

Head teacher Ela Smykla says the aim of the supplementary weekly school is to "ensure our kids will remember [their heritage] and speak Polish".

Classes are held for three hours on Saturday mornings. Pupils learn about Polish language, history, geography and religion, and there is singing and dancing for younger children.

It has been run from a number of different schools, and is currently based at Huxlow Academy in Irthlingborough.

Attendance peaked in 2019, and since then, the school has had about 340 students each year.

Parents are charged £120 per semester for their first child, and £90 for the second, with any additional child exempt from fees. There are two semesters per year.

Ms Smykla says: "I am incredibly proud of our school and everything we have accomplished together.

"Our staff is truly dedicated, working tirelessly to provide the best possible service to our students.

"I take great pride in the size of our school and the trust that parents place in us by sending their children every Saturday."

But since Brexit, Ms Smykla says "things have definitely changed".

"We've seen a lot of families and parents leaving, and six out of between 18 and 20 teachers have left," she says.

Ms Smykla says this might affect the future of the school.

"At some point we may not have students to attend to our school, or we will have to close some classes."

Wellingborough Polish School

Wellingborough Polish SchoolOn 1 May 2004, Poland became one of 10 new European Union member countries.

Many EU countries anticipated a big movement of people from east to west after expansion, and introduced transitional controls to limit this movement.

But the Labour government chose not to introduce these. As a result, migration to Britain from the rest of Europe significantly increased, with most of the extra numbers coming from Eastern Europe.

According to the Office for National Statistics, the Polish-born population of the UK was 743,000 in 2021, up from 579,000 in 2011.

In the latest census in 2021, just over 10,200 North Northamptonshire residents said they were born in Poland.

This represented 2.8% of the district's population, making Poland the second-most represented country of birth after England.

This figure was up from just over 6,000 in 2011.

In 2019, Poland's ambassador to the UK wrote to 800,000 Polish nationals, advising them to "seriously consider" returning home after Brexit.

Arkady Rzegocki said living standards in Poland were improving, providing "a very good opportunity to come back".

Karolina, chairwoman of the school's parent governors, came to the UK in 2003 as a student.

Her three daughters, Amelia, Lilly and Vivienne, have either attended or are still at the school.

She says she had always wanted to them to be able to communicate with family in Poland, especially their grandparents.

"Of course, at home we have Polish TV. We try to talk as much as we can in Polish so they will not lose that confidence to speak, but mainly it was [because] I do want them to recognise they are, somewhere inside, still Polish, and know all the traditions; that school process we went through as young kids."

She says they did not always want to attend, and there were sometimes "big dramas" about going to school on a Saturday, but that it had paid off.

"It has benefitted my eldest daughter as the points from her Polish A-level helped her get into university, and my parents and grandparents are happy to be able to communicate with them easily," she says.

'It was challenging'

Submitted

SubmittedPawel moved to the UK in 2005. He met his wife, who is also Polish, in Corby where they live with their son Jan, 13, and daughter Mircelina, eight, who were both born in England.

In sending them to the school, Pawel says they had "basically gifted [Jan] a GCSE for free" as he could read, write and speak Polish as well as if he had attended school in Poland.

But he says sending the children to school on Saturday, after five days of mainstream education, had not always been easy.

"It was challenging because our son didn't understand why he had to go to school six days a week," he says.

"When everybody was having Saturday off, we had to wake up early to travel to Wellingborough."

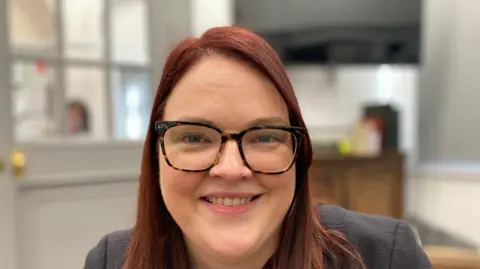

Justyna Nowak

Justyna NowakJustyna Nowak, a GP working in Northampton, moved over in 2006, and lives in Wellingborough with her husband and their five children - two sons and three daughters - aged between three and 13.

All attend the Polish school.

Dr Nowak says: "I think it's important for their identity. Knowing your ancestors; knowing your history is really important, and I didn't want them to get lost.

"They are taught how to read and write in Polish and I don't think on my own, especially as a working parent, I'd have been able to teach that."

'It's really positive to have such a diverse community'

Wrenn School in Wellingborough is a co-educational comprehensive and sixth form with about 1,500 students.

Principal Laura Parker says: "We've got about 30% of students who have English as an additional language (EAL), and that ranges across all sorts of different languages.

"We do something called Diversity Day, where they are able to share their languages and traditions and things that happen in different cultures, so that our students can be really open to all the sorts of different cultures that are going on."

The school has an EAL team that works with students when needed. Polish is also taught as an option language for students at GCSE and A-level.

All schools receive funding for EAL pupils for up to three years from their date of entry to the UK.

For the current last financial year (2024-25), secondary schools got £1,585 per pupil per year and primary schools got £590.

Mrs Parker says most of the school's EAL students will have entered the UK while at primary school, meaning they no longer qualify for the payments.

But she says the school uses the funding it does receive to employ EAL assistants and create a "hub space" for those who need it.

"We have a range of children, from those that have got to the UK and have no English at all, to children that were born in the UK but speak different languages at home," she says.

Their level of acquisition determines the level of support they receive, she says.

Those needing the most help are taken out of mainstream classes and taught English.

"Sometimes there will be teaching assistants in class where pupils have very low levels of acquisition to help them navigate a classroom and what that's like in a different language," she says.

"I think it's a really positive thing for students to have such a diverse community."

She says the number of languages spoken in school does not impact on the school, the pupils or their learning.

"They will know if there's people in their class who speak another languages and we really encourage them to talk about the fact that it's a good thing to have multiple languages," she says.

Mrs Parker says the school is "still working" on communication with parents who might not speak English, and try to translate things such as letters home where they can, but rely on families to tell them if they need that help.

The school also sends most things electronically so parents can use online translation services, such as Google Translate, she says.

Follow Northamptonshire news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, Instagram and X.