What happened in the Channel Islands during WW2?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Channel Islands were the only part of the British Isles to be occupied by the Germans during World War Two with islanders enduring five long, harsh years under Nazi rule.

From 1940-1945 Germans set up the only concentration camps ever established on British soil and turned the islands into an "impregnable fortress" on the orders of Adolf Hitler.

Hundreds of islanders were deported to German prisons, while those who remained nearly starved as the war approached its end.

Jersey and Guernsey were liberated on 9 May 1945, and Sark the following day. Most of the inhabitants of Alderney, who had been forced to leave, could not safely return until 15 December - now marked as Homecoming Day.

In 1940 the German army, the Wehrmacht, invaded Poland and the Low Countries before advancing through France.

As the remains of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) were rescued from Dunkirk, Channel Island sailors reported seeing German troops occupying the peninsulas of Normandy and Brittany.

The Channel Islands were left defenceless when Britain pulled its troops out and declared the islands demilitarised.

Islanders faced the choice of remaining and risking invasion or leaving their homes for safety on the mainland.

Hundreds queued for boats from St Peter Port and St Helier, while nearly the whole population of Alderney left.

In Jersey, there were reports of people driving to the harbour in expensive cars, then leaving the vehicles on the quayside with the keys in the ignition for anyone to drive away.

On 28 June 1940, German bombers attacked the islands as farmers were lined up at the harbours of St Peter Port and St Helier weighing and preparing vegetables for export.

The Luftwaffe pilots, perhaps mistaking the assembly of men and machines for military units, started to drop bombs.

The red of burst tomatoes, mingled with the blood of dying and injured men, ran on to the roads and by the time the bombers left, 44 Channel Islanders were dead.

The BBC broadcast an urgent message that the islands would not oppose any invasion and there were no more attacks, but two days later the first troops landed.

How did life change?

There was a cordial start to the occupation and stores did brisk business as soldiers bought souvenirs to send back to Germany.

The clocks were put forward an hour to coincide with German time and motorists were ordered to drive on the right, causing a flurry of accidents. There was a 23:00 curfew.

On 6 June 1942, the Germans ordered islanders to surrender their radios so they could not follow BBC News.

While many radios were handed in, hundreds of people managed to keep them or make crystal sets.

Many islanders were caught and punished for spreading news. They included Harold Le Druillenec, a Jersey schoolmaster who was arrested in 1944 for anti-German activities.

He was deported and held in German concentration camps including Belsen.

Huge construction works were carried out on all the islands built by forced labourers and slave workers.

When the first slaves arrived at the end of 1941 islanders were shocked as many of the prisoners were starving and dressed in rags.

The slaves were put to work building fortifications, while many islanders resolved to help them, either by feeding or offering shelter to those who escaped.

Alderney Museum

Alderney MuseumHitler ruled any men not born in the islands should be deported to Germany with their families.

In September 1942 people were given a few hours notice to be at the harbour.

As the first boat full of deportees sailed from St Helier, a mass of islanders watched singing We'll Meet Again.

Nearly 2,500 Channel Islanders were sent away and held in prisons or internment camps until the end of the war.

Collaboration and resistance

While there was no resistance to the initial landings, some islanders tried to undermine the occupiers.

Some daubed V for victory on buildings, or incorporated the symbol in stamps or stonework, including the V in the paving of Jersey's Royal Square.

Others, including the Guernsey Underground News Service (GUNS), shared the news, but several members were caught.

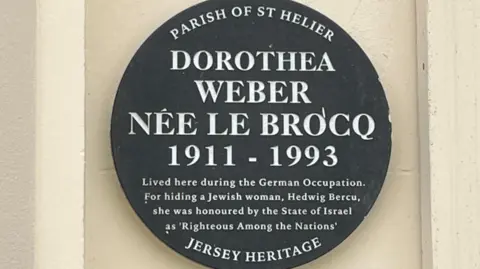

In Jersey a communist cell led by Norman Le Brocq worked to undermine the Germans.

Its most spectacular coup came shortly before liberation when it helped a German deserter destroy the Palace Hotel, an important German headquarters.

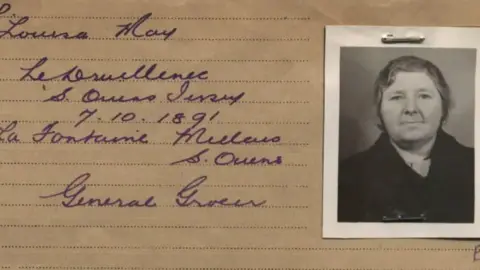

Jersey Heritage

Jersey HeritageAccording to the Falla Archive, 21 people from Jersey and eight from Guernsey did not return from Nazi prisons, labour and concentration camps after the war.

They included Louisa Gould in Jersey who was sent to the concentration camp at Ravensbrück, after she was caught trying to help the escaped Russian slave Feodor Polykarpivitch Burriy, known as Russian Bill.

Some people tried to escape from the islands, mainly by boat. But they were in danger, not only from the Germans but also from the dangerous seas around the islands.

It became slightly easier after the Allies liberated the French coast in 1944 and one of those who successfully got away was Sir Peter Crill, a future bailiff of Jersey.

But there was little chance of organised resistance in the islands where the geography allowed nowhere to hide and where, at times, there was one German soldier for every three islanders.

Just as in France and other occupied countries, there were also those who assisted the Germans.

Some businesses took German money to help build the fortification while some women were referred to as "Jerrybags" after forming relationships with the soldiers.

Others took a more active role in denouncing their neighbours. Some suggested the occupiers look in the coal shed of a house to find a hidden radio, illegal food or an escaped slave.

'No fighting. Let 'em rot'

Sir Winston Churchill recognised the Channel Islands, being so close to occupied France, would be hard to retake and almost impossible to keep.

He was happy to let the Germans expend huge efforts and materials on fortifications that would never be needed.

It is thought that about 10% of all the steel and concrete used in Hitler's Atlantic Wall was used to make the bunkers, guns and casemates in the Channel Islands.

PA

PAIn the margins of an official report in September 1944 about the islands, Churchill wrote: "No fighting. Let 'em rot."

Although it has never been clear whether he meant the German occupiers or the Channel Islanders, there was no attempt to retake the islands, even after France had been liberated.

The garrison and the people had to wait until the end of the war in Europe.

When the Germans arrived they demanded all Jews be registered. Fewer than half declared themselves, while some went into hiding.

Island leaders refused to implement the German order that all Jews should wear the yellow star.

The islands' governments were also complicit in helping Jewish shop owners who were forced to sell their businesses.

Many were "sold" for a nominal fee and bought back by their owners at the end of the war.

Not all Jews remained hidden and some were deported to Germany and imprisoned. Three women in Guernsey died in Auschwitz after confessing their faith in 1942.

The occupation in Sark was less severe than in Guernsey and Jersey but some of the island's small population were deported.

Alderney was almost deserted when the Germans arrived and the invaders were able to build and fortify the island.

They set up four camps for slaves and forced workers who laboured long hours to build bunkers, gun emplacements and walls.

Russian and Jewish prisoners were held at the SS concentration camps called Norderney and Sylt.

The island was also used as a place to punish people from the other Channel Islands. It is believed nearly 8,000 people were imprisoned in Alderney and a recent study suggests between 641 and 1,027 died.

Why was the last winter so severe?

As the Allies advanced and liberated the French Channel ports they cut off the German food supply chain to the islands.

Rations were reduced and gas and electricity cut leaving people with no light or heating.

Those lucky enough to have candles would struggle to find matches and people would go to bed at dusk, wearing all their clothes.

Many starving slaves broke out of camps to steal what they could, risking death in the process.

Finally, after negotiations between the British and Germans, the Red Cross was given permission to bring relief supplies into St Peter Port and St Helier.

Between Christmas 1944 and the new year of 1945, the SS Vega brought thousands of Red Cross parcels to the islands, saving the lives of countless people.

What finally brought liberation?

As the Allies pushed closer to Germany, islanders felt forgotten and the German occupiers were isolated.

In May 1945, the European war reached its apocalyptic end in the ruins of Berlin. Hitler took his own life and a week later Germany surrendered.

Churchill's victory speech, including the line: "Our dear Channel Islands are to be freed", was broadcast across Royal Square, Jersey.

On 9 May, soldiers from HMS Bulldog landed in St Peter Port while HMS Beagle sailed into St Helier.

In Guernsey the Union Flag was first raised over the States offices, then the Royal Hotel, before it was also raised at the Royal Court where the crowd of between 1,500 and 2,000 broke into a spontaneous rendition of God Save the King.

In Jersey the Union Flag was raised from the Harbour Master's Office and from the balcony of the Pomme d'Or Hotel, Jersey, in front of what is now Liberation Square.

Celebrations were long and loud, children tasted their first sweets and women danced with Tommies. The National Anthem was sung along with Guernsey's Sarnia Cherie and Beautiful Jersey.

The last island to be freed was Alderney, where the garrison did not surrender until 16 May. Thousands of minefields had to be cleared before the majority of inhabitants could return on 15 December, a day still marked in the island as Homecoming Day.

After five long years of oppression, hunger, darkness and despair, the Channel Islands and their people were finally free.

The military began bringing order to the islands as German leaders were taken away. Some soldiers were kept on to help clear the thousands of mines and miles of barbed wire.

The escaped slaves who had been in hiding were sent back to Russia, where they were regarded with suspicion by the communist regime.

The islands were left with hundreds of fortifications, many of which remain, some decaying and empty. Others, such as the Batterie Lothringen in Jersey and Fort Hommet in Guernsey, have been restored.

Every year on 9 May crowds gather to remember those five long years that forever changed island life and celebrate what happened on that day in 1945.

Follow BBC Guernsey on X and Facebook. Follow BBC Jersey on X and Facebook. Send your story ideas to [email protected].