WW2 women pilots 'faced prejudice with humour'

Candy Adkins

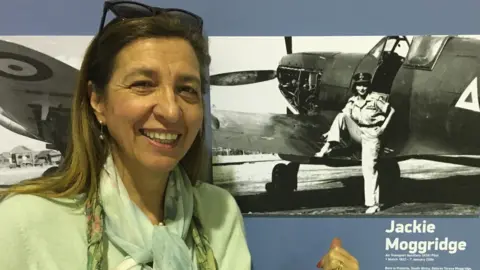

Candy AdkinsJackie Moggridge was 18 when she arrived in England with dreams of becoming an airline pilot.

In 1938 there were no aeronautical colleges in South Africa so she came to Witney, Oxfordshire, where she was the only woman on her aviation course.

Her resolve at such a young age was remarkable, even by modern standards, and in her lifetime she overcame discrimination and prejudice to make aviation history.

Nowadays her daughter, Candy Adkins, tries to spread the word of her mother's trailblazing endeavours to inspire and educate others.

Jackie Moggridge's achievements were numerous - she was the first woman in South Africa to do a parachute jump, she flew more than 1,400 aircraft as a World War Two ferry pilot, she was one of only five women to gain their RAF wings after the war, and she became Britain's first woman commercial airline captain in 1957.

"She was desperate to be a pilot," said Ms Adkins. "She did not see limits like other people would.

"She never thought 'I'm a woman, I cannot possibly do that', even though she was told it again and again - and it shocked her."

Just a year into her course at Witney Aeronautical College, war broke out in Europe and the college closed.

The teenage aviator initially trained on radar but in 1940 she was asked to join the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), delivering aircraft from factories and air bases or returning them for repair, often in a dangerous and damaged state.

Initially based an an all-women ferry pool in Hamble, Hampshire, the 19-year-old was the 15th woman to join the ATA, and the youngest.

"She flew 1,438 planes during the war," said Ms Adkins.

"In her lifetime, she flew 668 Spitfires. That doesn't include the Wellingtons, Blenheims, Hurricanes, Mosquitos… she flew 82 different types."

Candy Adkins

Candy AdkinsBut the ATA's women were often met with disbelief and ridicule, with fighter pilots sometimes refusing to hand over their aircraft and officers accusing the "silly girls" of poor flying after they had skilfully wrestled damaged planes to the ground.

"They got over all the prejudice with humour most of the time," said Ms Adkins.

"Whenever there was a crash, there was an inquiry to see whether it was the pilot or the plane's fault and it was always the plane's fault.

"Mum said she landed many a plane without undercarriage."

Out of 168 women in the ATA, 16 died, but despite the danger and discrimination, the women regarded their jobs as a privilege.

"At her age it was a big adventure," said Ms Adkins. "They took the prejudice because they felt amazingly lucky.

"There weren't loos, there were only urinals, so they used to go behind the hangar.

"They could not eat in the mess because they were women so they use to eat outside with their food on a tray.

"Their uniform was a skirt. Eventually they were allowed to wear trousers for flying but, even then, there was a sign outside saying 'will women please remove their trousers before entering the mess'."

Ms Adkins said, on one occasion, her mother was promoted but it was quickly withdrawn.

She also wrote to obtain official dispatches to prove her mother had gained her RAF wings in 1953 because people within the air force did not believe her.

Candy Adkins

Candy Adkins"They did not get medals, they weren't even allowed to get promoted," said Ms Adkins.

"She was promoted by mistake.

"Her commandant thought she was good and sent off for her to be promoted and they issued it, then withdrew it.

"She was immensely proud of getting her RAF wings, which no one believed.

"That must have been so hard in her lifetime, that RAF people did not believe her."

After the war, Mrs Moggridge completed her commercial flight training.

But when she made history by becoming Britain's first woman airline captain, she was not allowed to speak on the plane's tannoy in case the passengers were alarmed to hear a woman's voice.

Mrs Moggridge died in 2004 and her ashes were scattered over Dunkeswell Airfield, Devon, from a Spitfire.

The aircraft was ML407, which she had been the first to fly in 1944, straight from the factory.

Ms Adkins continues her mother's legacy by giving talks at airfields, clubs and events.

"I think it's really important to get the story out there," she said.

"There are no books or films with women pilots. Girls do not have enough women pilot heroines."

You can follow BBC Oxfordshire on Facebook, X (Twitter), or Instagram.