Why South Korea has been gripped by political instability

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt was around 23:00 on a Tuesday night when - out of nowhere - South Korea's president Yoon Suk Yeol declared martial law in the Asian democracy for the first time in nearly 50 years.

Explaining his decision, he mentioned "anti-state forces" and the threat from North Korea. But it soon became clear that it had not been spurred by external threats but by his own desperate political troubles.

The law was voted down just hours later - but it set in motion a string of events that have led to a state of political chaos in South Korea.

Who is Yoon and why did he impose martial law?

On 3 December, the country was stunned when Yoon said he was imposing martial law to protect the country from "anti-state" forces that sympathised with North Korea.

South Korean politicians immediately called Yoon's declaration illegal and unconstitutional. The leader of his own party, the conservative People's Power Party, also called Yoon's act "the wrong move".

Meanwhile, the leader of the country's largest opposition party, Lee Jae-myung of the liberal Democratic Party (DP) called on his MPs to converge on parliament to vote down the declaration.

He also called on ordinary South Koreans to show up at parliament in protest.

Thousands heeded the call, rushing to gather outside the now heavily guarded parliament. Protesters chanted "no martial law" and "strike down dictatorship".

And lawmakers were also able to make their way around the barricades - even climbing fences to make it to the voting chamber.

Shortly after 01:00 on Wednesday, South Korea's parliament, with 190 of its 300 members present, voted down the measure. President Yoon's declaration of martial law was ruled invalid.

The last time martial law was declared in South Korea was in 1979, when the country's then long-term military dictator Park Chung-hee was assassinated during a coup.

It has never been invoked since the country became a parliamentary democracy in 1987.

But why did he do it?

Yoon was relegated to a lame duck president and reduced to vetoing bills passed by the opposition, a tactic that he used with "unprecedented frequency", said Celeste Arrington, director of The George Washington University Institute for Korean Studies.

Then on the week on 3 December, the opposition slashed the budget the government and ruling party had put forward.

Around the same time, the opposition was moving to impeach cabinet members, mainly the head of the government audit agency, for failing to investigate the president's wife.

With political challenges pushing his back against the wall, Yoon went for the nuclear option - pressing the red button of martial law.

What was the response?

The response came quickly - tens of thousands of protesters called for Yoon to be impeached, with polls saying three-quarters of South Koreans wanted to see him go.

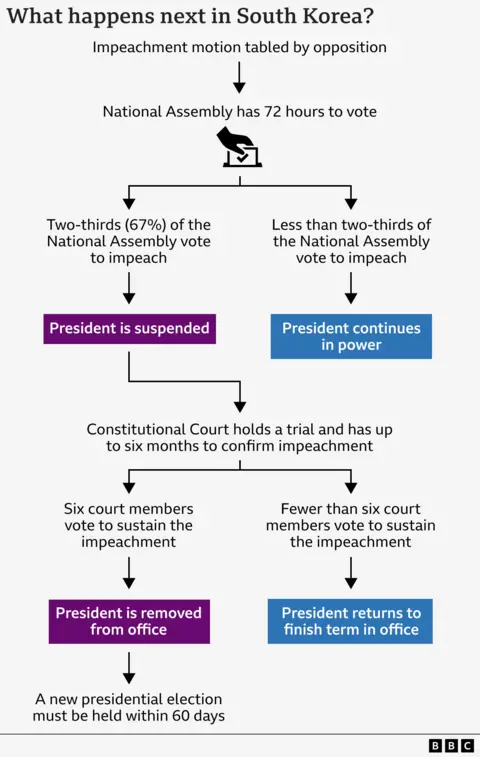

Opposition lawmakers quickly filed a motion for him to be impeached - which went to parliament.

Opposition members make up 192 seats of Korea's 300 seat parliament - so they needed eight members of the ruling party to vote in favour of impeachment, in order to reach the 200 votes needed to pass the motion.

But members of Yoon's People Power Party (PPP) boycotted the vote - walking out of parliament in protest.

But the opposition was undeterred. They said they would keep filing motions for Yoon to be impeached until they succeeded.

And just a week after - on 14 December, they did.

Some of Yoon's own PPP voted with the opposition - giving them the 200 votes needed.

The country's Prime Minister Han Duck-soo, was named as the acting president - and took over Yoon's duties.

But now he too has been impeached - the first time an acting president has been impeached in South Korea since it became a democracy.

Why did South Korea impeach its president - again?

At the heart of the issue is Yoon's impeachment.

Korea's Constitutional Court is typically made up of a nine-member bench. At least six judges must uphold Yoon's impeachment in order for the decision to be upheld.

There are currently only six judges on the bench, meaning a single rejection would save Yoon from being removed.

The opposition had hoped to get three additional nominees on the bench, something that would help improve the odds of Yoon getting impeached.

But earlier this week, Han blocked the appointment of the three judges - leading the opposition to file an impeachment motion against him, saying that he was refusing demands to complete Yoon's impeachment process.

And unlike the 200 votes required for Yoon's impeachment, only 151 votes are needed to pass an impeachment bill against the acting president - meaning the opposition did not need the ruling party's support to do so.

On Friday, a total of 192 lawmakers voted for Han's impeachment.

He will be suspended from his duties as soon as he is officially notified by parliament.

So what now?

It's hard to say.

Finance minister Choi Sang-mok is set to replace Han as acting president, and has pledged to do all he can to end the country's political turmoil.

"Minimising governmental turmoil is of utmost importance at this moment," Choi said in an address shortly after his appointment, adding that "the government will also dedicate all its efforts to overcoming this period of turmoil".

But it's unclear if the opposition might move to impeach Choi, if they deem him to be uncooperative.

The markets have also reacted to the news. On Friday, the Korean won plunged to its lowest level against the dollar since the global financial crisis 16 years ago.

What lies ahead for Yoon's presidency, his party's rule and what happens next in one of the world's most important economies however, are still questions that remain unanswered.