Macron visits Greenland in show of European unity and signal to Trump

Michel Euler/Pool via Reuters

Michel Euler/Pool via ReutersIn a sign of Greenland's growing importance, French President Emmanuel Macron is visiting the Arctic island today, in what experts say is a show of European unity and a signal to Donald Trump.

Stepping foot in the capital Nuuk this morning, Macron will be met with chilly and blustery weather, but despite the cold conditions, he'll be greeted warmly.

"This is big, I must say, because we never had visits from a president at all, and it's very welcomed," says veteran Greenlandic official, Kaj Kleist.

Nuuk is a small city of less than 20,000 people, and the arrival of a world leader and his entourage, is a major event.

"I think that people will be curious, just hearing about it," says consultant and podcast host Arnakkuluk Jo Kleist. "I think they'll be interested in, what his message is going to be."

"He's the president of France, but he's also an important representative of Europe. It's a message from the European countries that they're showing support, that Greenland is not for sale, and for the Kingdom of Denmark," says Arnakkuluk Jo Kleist.

"These last months have created some questions about what allies we need, and also about what allies do we need to strengthen cooperation with," she says.

France's president is the first high-profile leader to be invited by Greenland's new prime minister, Jens-Frederik Nielsen. Talks will focus on North Atlantic and Arctic security as well as climate change, economic development and critical minerals, before Macron continues to the G7 summit in Canada.

Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen is also attending, and called the French president's visit "another concrete testimony of European unity" amid a "difficult foreign policy situation in recent months".

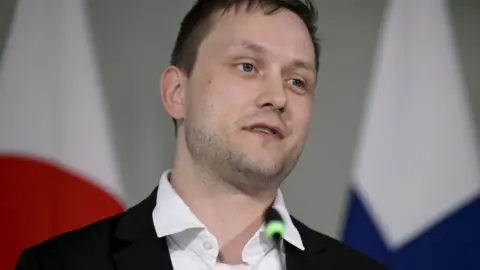

Roni Rekomaa/Reuters

Roni Rekomaa/ReutersFor several months Greenland, which is a semi-autonomous Danish territory with 56,000 people, has come under intense pressure as US President Donald Trump has repeatedly said he wants to acquire the vast mineral-rich island, citing American security as the primary reason and not ruling out using force.

"Macron is not coming to Greenland just for Greenland's sake, it's also part of a bigger game, among these big powers in the world," says Kleist.

France was among the first nations to speak up against Mr Trump, even floating an offer of deploying troops, which Denmark declined. Only a few days ago at the UN's Oceans conference in Nice, Macron stressed that "the ocean is not for sale, Greenland is not for sale, the Arctic and no other seas are for sale" - words which were swiftly welcomed by Nielsen.

"France has supported us since the first statements about taking our country came out," he wrote in a Facebook post. "It is both necessary and gratifying."

That Macron is coming is a strong message itself, reckons Ulrik Pram Gad, a senior researcher at the Danish Institute for International Studies.

"The vice presidential couple weren't really able to pull it off," he says, referring to JD Vance and his wife Usha's scaled-back trip in March and lack of public engagements. "That, of course, sends a message to the American public, and to Trump."

Jim Watson/Pool via Reuters

Jim Watson/Pool via ReutersIt also highlights a shift, as Greenland's leaders consolidate relations with Denmark and the EU, "because we have to have allies in these problems," says Kaj Kleist, alluding to US pressure.

"I think it's a good time for Macron to come through here," Kleist adds. "They can talk about defence of the Arctic before the big NATO meetings… And hear what we are looking for, in terms of cooperation and investment."

However, opposition leader Pele Broberg thinks Greenland should have hosted bilateral talks with France alone. ""We welcome any world leader, anytime," he says "Unfortunately, it doesn't seem like a visit for Greenland this time. It looks like a visit for Denmark."

Relations between the US and Denmark have grown increasingly fractious. US Vice President JD Vance scolded the Nordic country for underinvesting in the territory's security during his recent trip to an American military base in the far north of Greenland. Last month Denmark's foreign minister summoned the US ambassador in Copenhagen, following a report in the Wall Street Journal alleging that US spy agencies were told to focus efforts on Greenland.

Then, at a congressional hearing on Thursday, US Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth appeared to suggest under tense questioning that the Pentagon had prepared "contingency" plans for taking Greenland by force "if necessary".

Denmark, however, has treaded cautiously. Last week its parliament green-lighted a controversial bill allowing US troops to be stationed on Danish soil, and is spending another $1.5bn (£1.1bn) to boost Greenland's defence. That heightened military presence was on show this weekend as a Danish naval frigate sailed around Nuuk Fjord and helicopters circled over the town.

"Denmark has been reluctant to make this shift from having a very transatlantic security strategy to a more European strategy," assesses Gad, but that's changed in recent months.

With rising tensions and increased competition between global powers in the Arctic, the EU is also stepping up its role. Earlier this month the trade bloc signed a deal investing in a Greenland graphite mine - a metal used in batteries - as it races to secure supplies of critical minerals, as well as energy resources, amid China's dominance and Russia's war in Ukraine.

Leiff Josefsen/Ritzau Scanpix/AFP via Getty Images

Leiff Josefsen/Ritzau Scanpix/AFP via Getty ImagesFor France, the visit to Greenland ties into its policy to boost European independence from the US, suggests Marc Jacobsen, associate professor at the Royal Danish Defence College.

"This is about, of course, the changed security situation in North Atlantic and the Arctic," he explains. "It's a strong signal. It will show that France takes European security seriously."