How the Grateful Dead built the internet

Getty Images

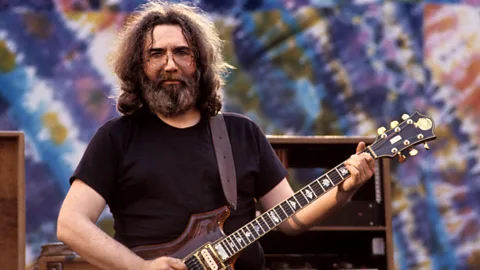

Getty ImagesBefore the the internet took over the world, psychedelic rock band The Grateful Dead were among the first – and most influential – forces at the dawn of online communication.

The Grateful Dead weren't just a band. They were a lifestyle. Originally a local blues outfit known as the Warlocks, they soon ascended to the rank of house band for author Ken Kesey's "Acid Tests", and by the late 1960s became a force to be reckoned with on the national touring scene. The Dead, as many call them, helped define San Francisco's characteristic counterculture, fusing folk and Americana influences with Eastern spirituality – as well as forward-thinking experiments with futuristic tools.

But the Dead shaped far more than rock, psychedelia and '60s drug culture. Thanks to a group of music-loving tech enthusiasts, the Dead popularised what some call first real online community. Generations later, the ideas formed in this pioneering digital space still reverberate through our daily lives.

Fans of the Dead, known as "Deadheads", were inspired by the band's embrace of all things technological, from their pioneering sound systems to their immersive multimedia visuals. Many fans were technologists and engineers themselves, working in Silicon Valley or at universities around America with access to early internet technology – which they were using by the late 1970s to swap hot commodities like Grateful Dead setlists and illegal drugs.

In the 1980s, years before the World Wide Web, a virtual online community emerged called the Well (the Whole Earth 'Lectronic Link). Centred on the San Francisco Bay Area of California, the Well not only thrived in its own right, but proved to be one of the most influential factors in the birth of the internet as we know it today. And its long life was in large part thanks to fans of the Grateful Dead.

The Well was borne out of a project started by writer, activists and businessman Steward Brand, who began producing a print publication he called the Whole Earth Catalog in the 1970s. Inspired by the back-to-the-land movement which was seeing thousands of hippies across America start up communes, the Catalog was designed to provide "access to tools" – its slogan – that anyone could use to build their lives around the ecological and spiritual principles of the movement. That meant that alongside the physical tools it offered for sustainable living – like solar stills, looms, and seed kits – it featured an array of books and pamphlets by thinkers – like Buckminster Fuller and Marshall McLuhan – meant to provide insight into how to lead better, more thoughtful lives. The Catalog was enormously influential, and not just on hippies. Apple cofounder Steve Jobs called it "one of the bibles of my generation" in a famous 2005 speech.

Getty Images

Getty Images"We are as gods and might as well get used to it," the Catalog argued in the introduction to the spring 1969 edition, proposing the Catalog and its offerings as a means to develop an "intimate, personal power" to counteract the top-down, dominant "remotely done power and glory" of impersonal government and big business.

The Catalog proved very popular, selling a million copies by 1972. Larry Brilliant, a doctor and activist who also happened to be the owner of computer company Networking Technologies International, approached Brand with the idea of putting the Catalog online. It was a radical idea at a moment when most people had never even heard of the internet. But Brand saw the potential in giving readers of the Catalog a place to talk to each other. Brilliant provided the money and equipment while Brand helped onboard users and build the community's culture, and in 1985, the Well went online.

The Well was a "bulletin board system" (BBS), an early text-based approach to online communication that long predated the mainstream internet. People could dial into a BBS using a computer and a phone line, where they would send messages and share files. But the Well was more advanced than other BBS's. In the 1980s, these systems typically ran off a single modem, usually in someone's home, and only one person could dial in at a time. Real-time conversation between multiple users was impossible. The Well, operating out of the Whole Earth Catalog's San Francisco office, was among the first to change that. It was professionally run on command-line PicoSpan software, and sported the hardware necessary for multi-user use and conversation – fifty people could be online chatting at the same time. This was a revolutionary experience.

And the Well was very different than purely commercial conferencing services like CompuServe that were around at the time: it was founded with a countercultural ethos at heart, based in the Whole Earth Catalog's do-it-yourself message, and was meant to encourage people from different walks of life to mix and mingle with each other, provoking interesting conversations and social change.

Howard Rheingold was a freelance writer working from home, looking for ways to socialise – and procrastinate. Having been a devoted reader of the Whole Earth Catalog since its first issue, he was early to the Well, signing up soon after it was launched to the public in 1985.

"Writing is a lonely affair," he says. "You're alone there with your typewriter, and your words. Instead of hanging out at a bar or a coffee house, I found that I could log into the Well and have that kind of conversation in between writing things." Rheingold saw the Well as a demonstration of the promise of electronic connectivity. He coined the term "virtual community" to describe the Well in his 1992 book of the same name, Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier. In the book, he observed that "[most] people who have not yet used [networked communication] remain unaware of how profoundly the social, political and scientific experiments under way today via computer networks could change all our lives in the near future".

At its launch, the Well was populated by a diverse group of conversationalists. The canny owners gave free invitations to journalists, computer enthusiasts and other prominent figures in a culture centred on Silicon Valley-style experimentation and forward thinking. The Well emphasised independence and ownership: the login screen told users "You own your own words". Many see it as the first time user-generated content was recognised as the inherent value proposition of an electronic tool.

Getty Images

Getty Images"It was a bit of an eclectic mix with a heavy countercultural flavour," says Rheingold. One of the recipients of these free invitations was David Gans, a Bay Area musician, DJ and Deadhead who was interested in the idea of finding an online home for the thriving Grateful Dead community. The Well was a perfect fit. Alongside cofounders Bennett Falk and Mary Eisenhart, he spun up the Grateful Dead forum.

Eisenhart, at the time the editor of a Bay Area computer magazine MicroTimes, remembers how Grateful Dead fanzines made her think about connecting members of the fandom. "[The fanzines] would get these heartrending letters from people who thought they were the only Deadheads in their state, but now at least they could connect with other Heads," she says. "I was very drawn to the ability to overcome the barriers of time and space to connect with those you had some actual affinity with."

Before long, the Well's Grateful Dead space exploded in popularity. At $2 an hour to dial in (about $6 or £4.50 today) along with its $8 membership fee ($23 or £17.20 today), the Deadheads devotion to endless discussion of their favourite band helped fund the entire platform.

What was there to talk about? Well, a lot, according to Gans. Not all Grateful Dead fans went "over the wall" to the rest of the Well. Plenty stayed within their bubble, chatting away. The single forum for Deadheads got so unwieldy it had to be split into multiple forums, with separate ones popping up for tours, tickets and tape recordings of live shows, says Gans. There was also the deadlit conference – "conference" being the Well's terminology for an individual, topic-based forum within the larger platform – where users could talk about the Dead's connections to literature, and dissect the poetry of the bands lyricists Robert Hunter and John Perry Barlow.

More like this:

• The failure that started the internet

• The people stuck using ancient Windows computers

• The hidden world beneath the shadows of YouTube's algorithm

Barlow himself was a major figure at the intersection of the Grateful Dead and the history of the internet. Raised on a ranch in Wyoming, and introduced to LSD by Timothy Leary himself during college, he ended up falling in with the Dead in the 1970s. He wrote songs for the band before heading back to take over his family ranch, where his distance from the Bay Area contributed to his interest in the burgeoning field of personal computing and online connection.

Gans remembers interviewing him in 1982, a few years before the Well came into being. "He said [of the Deadheads], 'this is a community without a physical location.' And that really stuck with me." Grateful Dead fans already a nationally distributed group which came together regularly at concerts, and through the Dead's sizeable mailing list. In fact, the Well wasn't even Deadhead's first foray into digital communication. According to Gans, one of the first non-technical groups that formed on Arpanet, a precursor to the internet run by universities and the US government, was devoted to discussion of the Grateful Dead. A full embrace of cyberspace was a natural next step.

Sign up for Tech Decoded

For more technology news and insights, sign up to our Tech Decoded newsletter. The twice-weekly email decodes the biggest developments in global technology, with analysis from BBC correspondents around the world. Sign up for free here.

Barlow wasn't immediately on board, however. Gans recalls his skepticism: "[He said] 'Well, I'm not sure I want to be part of anything where you have to make up a nickname for yourself.'"

But it wasn't long before Barlow embraced the Well, and soon, he came a pioneering force in as the internet launched into the mainstream.

He was the first person to apply Neuromancerauthor William Gibson's term "cyberspace" to the emerging network of computer and telecommunications systems linking people together around the globe. Barlow started referring to cyberspace as an "electronic frontier," drawing on his experiences growing up in Wyoming, in the Mountain West of America. The Well and other similar outposts, like Prodigy and The Source, were akin to the Wild West, writes Barlow, "vast, unmapped, culturally and legally ambiguous [...] hard to get around in, and up for grabs".

Barlow found a home within the Well's community of hackers, free speech enthusiasts and home computing pioneers. He quickly understood the Well's potential as a harbinger for the ways the internet would change the face of human communication forever. On the Well, Barlow engaged in long discussions, often debating with anonymous hackers and "phreaks" – or telephone hackers – about the role that networked communication was to play in the future of humanity.

After some run-ins with clueless law enforcement officers, Barlow recognised a growing need to defend the internet users against the overreach of institutions and governments who would want to control it. In 1990, he founded the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) – an advocacy group that fights for free-speech and other civil rights in the digital world.

"The next thing I know, he's founding the EFF and he's the Lord Mayor of cyberspace!", Gans says. The EFF quickly gained a national profile, and 35 years later, it's still one of the most influential forces in the world of technology policy.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor cyberspace denizens who wanted to engage in discussion and collaborate with the people who were shaping the future of virtual communities, the Well was the place to be. Alongside the Well's many Deadheads, members included technology journalists like John Markoff and Steve Levy; entrepreneurs Craig Newmark, founder of Craigslist; Steve Case, founder of AOL; homebrew computer enthusiasts like Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak; phone phreakers and hackers; libertarians; hippies; and even the founders of Wired magazine.

"Over the years, we've had people that were retired captains of submarines, we've had journalism professors. Jane Hirschfield, a very famous poet, is a regular, and John Carroll, who was a columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle, was the host of the media conference for many years," Gans recalls of the diversity of the Well's user base.

Many of these groups got into frequent disagreements. But that was part of the convivial spirit of the Well, says Rheingold. "You don't have a lot of great conversations with people who agree with each other about everything all the time," he points out. "Having some friction can help foster a lot of lively conversation."

At first, geography limited the Well's early users to the area surround its servers in San Francisco. Long-distance users had to pay requisite phone fees to dial in up, until 1990 when the Well was connected with the global internet.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThough there were never more than 5,000 or so users of the Well at its peak, its coverage and innovators of the day and its starring role in the creation of the EFF gave it an outsized reputation compared to more popular mainstream platforms like CompuServe and Prodigy. "Being on The Well kept me six months ahead of other people about what was actually happening on the internet," said tech executive Jim Rutt in a 2022 interview. It was a vital incubator for ideas and movements in computing, communications and social change.

But as it grew, Well faced some difficulties in governance, as Rheingold recalled, thanks to its libertarian free-speech ethos. "There was no police. It was consensus, which meant that in order to be sanctioned or to even be thrown out for bad behaviour, it required people on the Well to argue about it endlessly. I mean, thousands of posts." Lessons about moderation were learned, such as – for Rheingold – the vital importance of moderators being more like hosts at a party, becoming intensely proactive about what content to allow and promote. "Moderators are filters and sensors," he said, whereas hosts "greet people at the door, introduce them to each other, break up the fights."

As for the Well, it subsequently came under the ownership of a variety of different companies, including Salon magazine, which acquired it in 1999. And it's still around today, home to a slowly dwindling but loyal group of users, many of whom have been on the Well for almost 40 years, says Gans. He reveals that discussions are beginning on how best to archive and sunset the platform at some point in the future, preserving it for future generations to look back on.

Looking back at the history of virtual communities and social media since the Well's heyday, Rheingold reflects on the fact that small, dedicated affinity communities are a dying breed. "Facebook really put a damper on the proliferation of smaller communities of people with a shared interest," he says, in favour of larger platforms full of audiences which could be mined for data and served with advertisements. "Once your community members are the product rather than the customer, you don't have a community," says Eisenhart.

The Well represents a moment in history when, as founder Steward Brand put it in Rheingold's book, "personal computer revolutionaries were the counterculture". Long before the mainstreaming of social media and smartphones, a virtual community was a truly groundbreaking concept.

--

For more technology news and insights, sign up to our Tech Decoded newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights to your inbox twice a week.