What a US mission to control hurricanes taught us about deadly storms

Office of Noaa Corps Operations

Office of Noaa Corps OperationsAn ambitious project to weaken or divert hurricanes generated decades of suspicion and disagreement. What did we learn – and will it ever be revived?

As a grad student in the 1960s, Joe Golden flew on about a dozen of missions into the "eyewall" of a hurricane, where winds of 160mph (260km/h) battered the sides of his propeller-powered plane. "You could think of it as a ring of thunderstorms that often tower over 40,000ft [12,200m]," says Golden, who photographed hurricanes and gathered data on their development. "And it can also have frequent lightning in it," he adds, matter-of-factly. "So that's another hazard."

Crews on the "hurricane hunting" flights padded their planes' cabin and learned to never ignore orders to strap in when penetrating the wall. But meteorologist Hugh Willoughby recalls thrilling "white-knuckle" flights, including one when life rafts and safety equipment crashed against the ceiling when the plane began falling about 200ft (60m), its engine flaming out. "This is something I dearly loved: get up at 2:00 in the morning, put on my flight suit, lace up my boots," says Willoughby. "Go into the kids' room, pull the covers up over them, kiss them on the forehead, and go out and fly into a raging tempest."

Since the 1940s, pioneers like Willoughby and Golden have been embarking on daring flights into this most intense region of a hurricane to gather data that has expanded scientific knowledge about them and revealed how they develop their lethal force.

But, for a brief window of a few decades, the US Department of Defense and weather services flew missions into the eyewall with an even more ambitious objective: to not only observe these towering storms but to change them. Between 1962 and 1983, under the name Project Stormfury, navy pilots flew missions that released a silver compound into "the belt of maximum winds", just beyond the wall, in the belief that this region was violent but unstable. If so, perhaps it could be disrupted, calming the storm's vicious force.

Six decades after its first flights – and 42 years since it was cancelled – Stormfury veterans Golden and Willoughby remember a project that gave us vital knowledge that has helped to save lives. But along with this, US attempts to control storms have left behind a controversial legacy that has fueled distrust and conspiracy theories, with some unanswered questions that linger today.

From nuclear weapons to hurricane experiments

Both Golden and Willoughby recall that weather modification projects emerged at a time of enormous optimism following the end of World War Two, when there was a widespread perception that there was no limit to what science could achieve.

In the background was the nuclear bomb, says Kristine Harper, professor of history and sciences at the University of Copenhagen. After the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, there was expectation that constructive uses of atomic energy would follow, from nuclear power to "atomic gardening" that used radioactive substances to breed new mutant crops.

In 1946, newspaper and radio stations speculated that nuclear weapons might soon safeguard us from acts of God, recounts Harper in her book Make It Rain, an account of the US government's attempts at weather control. One New York Times article asked whether atomic energy "by its explosive force" could divert hurricanes away from cities. "You know, maybe we could destroy hurricanes with nuclear bombs?" laughs Harper. (This is not a good idea, meteorologists have repeatedly clarified.)

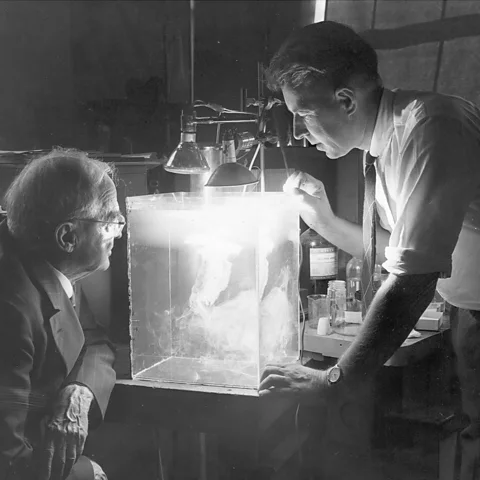

miSci- Museum of Innovation & Science

miSci- Museum of Innovation & ScienceEarly efforts to explore weather control were backed by veterans of the Manhattan Project, including John von Neumann and the so-called "father of the H-bomb" Edward Teller. But the most important breakthrough arrived, instead, inside a small, adapted freezer. At the research laboratory at US firm General Electric run by Nobel Prize-winning chemist Irving Langmuir, experiments had shown it might be possible to induce rain in clouds, by releasing substances that would cause supercooled water in the clouds to crystallise into snowflakes.

To test this "cloud seeding" technology in the field, Langmuir's assistant dropped dry ice out of the window of a single-engine airplane into a cloud hanging over western Massachusetts in November 1946. Langmuir was watching through binoculars from the ground below as snow began to fall in autumn toward a mountain called Mount Greylock. "This is history!" he cried down the phone to reporters, according to Caesar's Last Breath: The Epic Story of the Air Around Us by Sam Kean. At a time when many dreamed they might soon "be able to choose their weather much as they chose a radio station", writes Harper, the era of weather control appeared to be startlingly close at hand.

How to weaken a hurricane

Although little was known at the time about hurricane structure and behaviour, the US Navy and Army agreed to collaborate with Langmuir's lab on Project Cirrus, which aimed to understand if cloud seeding technology might be able to help extinguish hurricanes at birth, divert them off-course, or else weaken deadly tropical cyclones before they hit land.

Data gathered by weather balloons and aircraft indicated that hurricane clouds might contain large quantities of supercooled water, like the cloud Langmuir had seeded. During the hurricane season of 1947, on October 13, he convinced a navy crew to drop 80kg (200lb) of dry ice into an ice crusher in the belly of a B-17 bomber, sprinkling powder into a hurricane crossing Florida. This would be the historic first attempt to use this technology to modify a tropical cyclone. Although the adapted World War Two bombers did not have the technology to precisely target areas of the hurricane, their mission was enough to encourage the project's directors. Flying in a B-17 half-a-mile behind the seeding plane, a US Navy meteorologist observed overcast clouds turned into snowfall, noting the hurricane appeared to undergo "pronounced modification", recounts Fixing The Sky by Jim Flemming.

But in the days after, the unexpected happened. The hurricane that had been heading out harmlessly to sea, swerved from its course. Hitching westward, toward shore, it smashed the city of Savannah, Georgia, resulting in one recorded death and damage estimated at millions of dollars. Despite no firm evidence, Langmuir said he was "99% sure" the storm had changed course due to the seeding.

Stormfury's goal

Fears among the public and questions from meteorologists plagued Project Cirrus until it ended in 1952. But the US military maintained a strong interest in storm modification as their involvement in the Vietnam War escalated in the 1960s, says Harper.

"The Navy had a secret programme out at China Lake Naval Air Station [in California] where they were working on seeding techniques or weather-control techniques that were going to be used in Laos in Vietnam," she says. These classified missions, codenamed Operation Popeye, aimed to develop a "weather weapon" that could seed rain storms to wash out the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the North Vietnamese military supply line. For these efforts, says Harper, a civilian programme to research weather modification would provide the "perfect cover".

According to Stormfury's working hypothesis, by seeding the area just outside the eye wall with silver iodide, they could cause clouds to form a second eyewall, which in turn would compete with the inner eye wall. If they could make an eyewall to reform at a greater width, they expected that they would slow the hurricane's speed, Harper explains – like an ice skater extending their arms to slow their twirl.

Noaa

Noaa"If they could reduce the wind speed by 10% or so, that could make a difference in the category of intensity at landfall," says Willoughby, who started out flying storm-monitoring missions in the Pacific for the US Navy during the early 1970s. If a 100mph (160 km/h) wind could be slowed to (80km/h), it would actually lose 75% of its force. Hurricane Esther would provide the crucial test for the theory. Emerging around the islands of Cabo Verde (Cape Verde) in September 1961, the storm was becoming more intense as it swept through the Atlantic, about 400 miles (640km) north of Puerto Rico. On 16 September, an aircraft belonging to the US Weather Bureau flew through Esther's eyewall and dropped eight canisters of silver iodide into the raging winds. On a radar instrument monitoring Esther, US Weather Bureau planes detected a weakening of the eyewall. Despite other checks showing no change, it was declared a success, the Stormfury era was officially launched.

Penned in

The 1947 Project Cirrus mission still loomed large, despite research indicating the hurricane had already begun to turn before the seeding flight. As a result, Stormfury was restricted by a stringent set of requirements for how and where hurricanes could be modified. What resulted was a polygon zone drawn on a map: a confined experimental area, over the open Atlantic far from the US – yet close enough to Cuba that Fidel Castro accused the US of trying to attack his communist regime.

As a result of these restrictions, many storm seasons came and went during the 1960s, as Stormfury waited on call, frustrated. After another seeding mission in 1963, which produced mostly inconclusive results, Hurricane Betsy in 1965 appeared the perfect candidate, explains Golden, who joined Stormfury in 1964 and spent four decades at National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa). As the hurricane approached the Caribbean, Golden recalls Stormfury's leaders, the pioneering meteorologists Joanne and Robert Simpson, waiting on the line for Noaa's chief Robert White to give the go-ahead.

"We could only seed if the eye was within a prescribed area – and it was 50 miles [80km] outside the prescribed area," he says, so the crew stood down. Although a huge disappointment to the team, that turned out to be a stroke of luck, he adds, which avoided a repeat of Project Cirrus's controversy. "Hurricane Betsy made a very strange loop and it actually tracked to the south-west and hit just south of Miami."

Stormfury's biggest mission would finally arrive in 1969. On 18 and 20 August, 13 aircraft were involved in five runs across Hurricane Debbie, including a Navy A-6 Intruder jet, which dropped 1,000 silver iodide canisters each day. After nearly a decade of false starts, the data they gathered was jaw-dropping: most encouragingly, they documented a second eye wall emerging after seeding flights, with weaker winds, matching the hypothesis. During the two seeding days, winds decreased by 31% and 15%. Stormfury director R Cecil Gentry concluded that there was less than a one-in-10 chance of this happening naturally and his paper in the journal Science found that the data suggested the storm had been successfully modified by the scientists.

The end of Stormfury

Debbie was not the springboard to greater success that many involved in the project hoped. The last seeding flight flew in 1971, dropping canisters into the ill-defined eyewall of Hurricane Ginger with no discernible effect. Later the same year the Navy pulled support. The Navy's exit was in part because they no longer needed to test it, says Harper: "They were using the techniques in Vietnam and Laos – they didn't need to test them in the Atlantic anymore on hurricanes." Figures revealed in the Pentagon Papers in 1974 showed a far less cautious use of silver iodide and similar compounds in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, where Air Force and Navy planes dropped in a total of 47,409 canisters in 2,600 seeding missions.

In total, Stormfury's seeding flights had dropped canisters of silver iodide into four hurricanes on eight different days. Data across these flights found that on four days, winds reduced, falling in wind-speed by between 10% or more. Other days, nothing happened, which was blamed on flights failing to hit targets or poorly chosen storms.

Nasa

NasaWith few candidate storms in the Atlantic, during the 1970s, the US attempted to strike deals with Australia and the Philippines to run further tests on storms in the Pacific Ocean, off their coastlines. "The countries in the Pacific Rim just said, no," says Harper. "Just: 'No. That's not going to happen.'"

Around the time of Debbie's apparent success, the scientific basis of the project began to crumble. Images appeared to show some hurricanes spontaneously developed multiple concentric eyewalls, a phenomenon that Willoughby personally observed while flying through tropical storms with the Navy. If this was the case, Debbie's results could be mere coincidence.

At the same time, research increasingly questioned whether hurricanes contained the vast clouds of supercooled water that Stormfury believed could be seeded, instead finding ice, which would be unaffected by silver iodide. "Probably [either] one would have carried the day in an objective scientific evaluation," says Willoughby.

Although he had joined Stormfury with the intention of contributing to storm modification, being assigned to seeding crews, Willoughby never flew a seeding mission and found a project adrift. "Frankly, to my mind, the experiment did not seem to be well-thought-out in those later days," he says. Writing the final evaluation of the project in 1985, Willougby concluded that despite the team's determined efforts, "the expected results of seeding are often indistinguishable from naturally occurring intensity changes".

Did Stormfury fail?

To all involved, it was clear that Stormfury was never a normal meteorological study – instead, an experiment that began "at the wrong end", according to the Navy's project leader Pierre St Amand, quoted in Make it Rain. Because of the project's military value, and potential impact on civilian safety, Stormfury received millions of dollars in funding and support that most meteorological studies can only imagine. At the same time, hurricane science was still in its infancy, with not enough known to make accurate predictions about their interior structure and behaviour. "There was a germ of science," Harper summarises. But it's a pretty safe bet Stormfury would've remained in the lab if it weren't for military interests, she adds.

Nevertheless, the project delivered results that are still keeping us safe in other ways. "The aircraft measurements taught us a lot about hurricane structure and behaviour," says Joe Golden. "And those data helped to improve the models at the time." The funding it generated for meteorology helped address these knowledge gaps.

Willoughby, who is currently a research professor at Florida International University, says that since the start of Stormfury, the 24-hour forecast for hurricane's path has vastly increased in accuracy, from an error of more 120 nautical miles (138 miles/222km) to around 50 nautical miles (58 miles/93km), and forecast of hurricane intensity have improved from vague guidance to predictions accurate to within 10 knots (12mph/19km/h). Data gathered by the observer planes are still being researched, and instruments developed by Stormfury provide more accurate ways for airplanes to track hurricanes. Two highly modified P3 airplanes that were purchased for Stormfury – known affectionately as Kermit and Miss Piggy – continue to be used, some 50 years on.

Noaa

NoaaA future for storm modification?

For some, Stormfury is unfinished work. "Stormfury was one of the most frustrating scientific experiments in my life," Golden says. "In a nutshell, I think that Noaa gave up too soon."

Over the years, Golden has continued to make a case for government agencies to step up and show ambition to make hurricane modification a reality. Spurred by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, in which nearly 2,000 people died, Golden began working with the US Department of Homeland Security on "Hamp", the Hurricane Aerosol and Microphysics Program. "It was also aimed at weakening hurricanes, but it had a whole different approach. Instead of silver iodide, we were going to use very tiny salt aerosols as the seeding agent," he says. "Had the funding continued, we were going to do some field experiments – not on hurricanes initially, but just on cloud lines."

"The modeling results were very, very encouraging," he says, indicating that aerosols could not only diminish a hurricane's intensity but alter its course. "That's very important: if you can steer a hurricane like Katrina away from New Orleans, think of all the lives and the property damage that you would have saved."

"That had some very tantalising results but – yet again – the funding ran out," he says.

Willoughby, meanwhile, feels Noaa was right to end research. "It was a beguiling idea – what's not to like about making it rain in the desert or keeping typhoons and hurricanes from wrecking cities?" he asks. "But the science didn't work out."

For anyone with a theory of how to stop hurricanes, the hurdles are clear, says Willoughby. "What you do is you come up with an idea, you'd have to do a tabletop experiment or a small-scale field trial, and then use that to simulate it in a numerical model." Yet he doubts a solution will find a way to match the force of a tropical storm – even if we use nuclear weapons.

Stormfury was a humbling reality check, says Willoughby, pitting humans against the "immense" energy of a hurricane – estimated to be equivalent to a 10-megatonne nuclear bomb exploding every 20 minutes. "Perhaps some day, somebody will come up with a way to weaken hurricanes artificially," he writes in an email. "Wouldn't it be wonderful if we could do it."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram.