Still booting after all these years: The people stuck using ancient Windows computers

Grant Hindsley/ BBC

Grant Hindsley/ BBCCTRL+ALT+DEL, but make it forever. As technology marches on, some people get trapped using decades-old software and devices. Here's a look inside the strange, stubborn world of obsolete Windows machines.

Earlier this year I was on my way to a checkup at a doctor's office in New York City. As I rode up to the 14th floor, my eyes were drawn to a screen built into the side of the lift. Staring back was a glimpse into the history of computing. There, in a gleaming hospital full of state-of-the-art machines, was an error message from an operating system released almost a quarter of a century ago. The elevator was running Windows XP.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Microsoft. The company may not have the cultural cachet it did when that hospital lift was installed, but after a couple of decades playing catch-up Microsoft is back on top. The tech giant has been the first or second most valuable business on earth for the better part of five years. Today, Microsoft is betting on AI to carry it into the next generation of computing. But as it dumps tens of billions of dollars into bleeding-edge technology, some argue that one of Microsoft's most enduring legacies may be the marks it left on society long ago.

Since its launch in 1975, Microsoft has penetrated digital infrastructure so completely that much of our world still relies on aged, sometimes obsolete Windows software and computers, chugging along and gathering dust long after they first booted up. For people stuck using these machines, the ghosts of Windows' past are an ever-present feature of daily life.

Grant Hindsley/ BBC

Grant Hindsley/ BBC"In a way, Windows is the ultimate infrastructure. It's why Bill Gates is so rich," says Lee Vinsel, an associate professor at Virginia Tech in the US who studies the maintenance and repair of old technology. "Their systems are built into everything around us, and the fact that we have all of these ancient examples around is the story of the company's overall success. That's what's kind of amazing about Microsoft. For a long time, Windows was just how you got things done."

Even if you're a diehard Apple user, you're probably interacting with Windows systems on a regular basis. When you're pulling cash out, for example, chances are you're using a computer that's downright geriatric by technology standards. (Microsoft declined to comment for this article.)

"Many ATMs still operate on legacy Windows systems, including Windows XP and even Windows NT," which launched in 1993, says Elvis Montiero, an ATM field technician based in Newark, New Jersey in the US. "The challenge with upgrading these machines lies in the high costs associated with hardware compatibility, regulatory compliance and the need to rewrite proprietary ATM software," he says.

Microsoft ended official support for Windows XP in 2014, but Montiero says many ATMs still rely on these primordial systems thanks to their reliability, stability and integration with banking infrastructure.

And there are plenty of other surprising applications of old Microsoft products hidden in everyday life. In 2024, Windows was at the centre of a controversy across the German internet. It started with a job listing for Deutsche Bahn, the country’s railway service. The role being recruited was an IT systems administrator who would maintain the driver's cab display system on high-speed and regional trains. The problem was the necessary qualifications: applicants were expected to have expertise with Windows 3.11 and MS-DOS – systems released 32 and 44 years ago, respectively. In certain parts of Germany, commuting depends on operating systems that are older than many passengers.

Ryan Silver/ BBC

Ryan Silver/ BBCA Deutsche Bahn spokesperson says that's to be expected. "Our trains have a long service life and are in operation for up to 30 years or longer." Deutsche Bahn regularly modernises its trains, the spokesperson says, but systems that meet safety standards and prove themselves stable are generally kept in operation. "Windows 3.11 is also exclusively used in a small number of trains for operating displays only."

It's not just German transit, either. The trains in San Francisco's Muni Metro light railway, for example, won't start up in the morning until someone sticks a floppy disk into the computer that loads DOS software on the railway's Automatic Train Control System (ATCS). Last year, the San Francisco Municipal Transit Authority (SFMTA) announced its plans to retire this system over the coming decade, but today the floppy disks live on. (The SFMTA did not respond to a request for comment.)

In a brightly lit room in San Diego, California, you'll find two of the biggest printers you've ever seen, each hooked up to servers running Windows 2000, an operating system named for the year it was released. "We call 'em boat anchors," says John Watts, who handles high-end printing and post-processing for fine art photographers. The printers are LightJets, gigantic machines that use light, rather than ink, to print on large-format photographic paper. Watts says the result is an image of unparalleled quality.

Long out of production, the few remaining LightJets rely on the Windows operating systems that were around when these printers were sold. "A while back we looked into upgrading one of the computers to Windows Vista. By the time we added up the money it would take to buy new licenses for all the software it was going to cost $50,000 or $60,000 [£38,000 to £45,000]," Watts says. "I can't stand Windows machines," he says, "but I'm stuck with them."

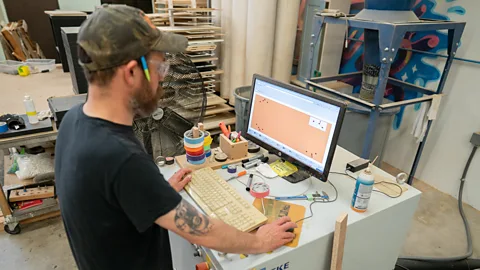

It's a common predicament with specialised hardware. Scott Carlson, a woodworker in Los Angeles, is steeped in the world of Microsoft thanks to CNC machines, robotic tools that cut or shape wood and other materials based on computer instructions.

"Our workhorse machine runs on Windows XP because it's older. That thing is a tank," Carlson says, but the same can't be said for the operating system. "We actually had to send the computer back to get completely rebuilt a few years ago because XP was getting more and more errors," he says "It was practically a brick."

Grant Hindsley/ BBC

Grant Hindsley/ BBCFor the people who use this old technology, life can get tedious. For four years, psychiatrist Eric Zabriskie would show up to his job at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and start the day waiting for a computer to boot up. "I had to get to the clinic early because sometimes it would take 15 minutes just to log into the computer," Zabriskie says. "Once you're in you try to never log out. I'd hold on for dear life. It was excruciatingly slow."

When it comes to decrepit computer systems that inhabit larger companies and organisations, the main culprit is generally "deferred maintenance", says M Scott Ford, a software developer who specialises in updating legacy systems. "Organisations put all their attention on adding new features instead of investing those resources into making improvements on [the basics of] what already exists," Ford says, which allows reliance on older technology to build up over time.

Most VA medical facilities manage health records using a suite of tools launched by the US government in 1997 called the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). But it works on top of an even older system called VistA – not to be confused with the Windows Vista operating system – which first debuted in 1985 and was originally built on the operating system MS-DOS.

The VA is now on its fourth attempt to overhaul this system after a series of fits and starts that dates back almost 25 years. The current plan is to replace it with a health record system used by the US Department of Defense by 2031. "VA remains steadfast in its commitment to implementing a modernised, interoperable Federal [electronic health record] system to improve health care delivery and positively impact patient care," says VA press secretary Pete Kasperowicz. He says the system is already live at six VA sites and will be deployed at 19 out of 170 facilities by 2026.

Grant Hindlsey/ BBC

Grant Hindlsey/ BBC"CPRS works, but at times [using] it was an overwhelmingly frustrating experience," Zabriskie says. Where modern health record systems have simple point-and-click interfaces, he would find himself typing out "c://" and the full file path to pull up a document.

"CPRS is 100% text, and it's all capital letters. The thing looks like a word processor from the '90s," Zabriskie says. "It's like learning how to use an old car. You have to memorise all these commands, and you're always running into errors. Something that should take a minute ends up taking half an hour because you forgot to type a dash somewhere."

It's a key example of a knowledge transfer problem that crops up as technology ages, according to Vinsel. "A lot of times when we're not updating infrastructure and keeping it healthy, you end up in a situation where there's only one guy in another state who knows how to keep the system running," he says.

Grand Hindsley/ BBC

Grand Hindsley/ BBCSometimes, government facilities in particular hang on to ancient software because its simplicity makes security easier to maintain, Vinsel says. "But there are all kinds of opportunities for failure here, especially when you get increasingly complex systems hooked up to the internet and companies stop supporting old software. Cybersecurity is a huge worry around this issue."

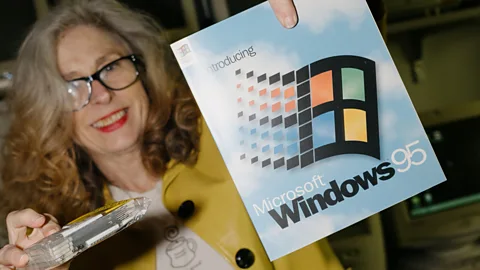

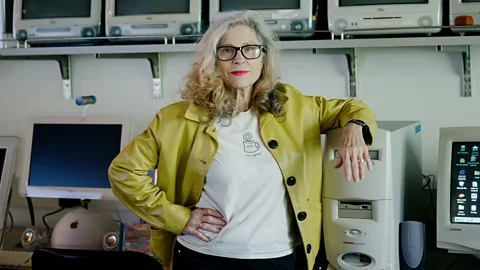

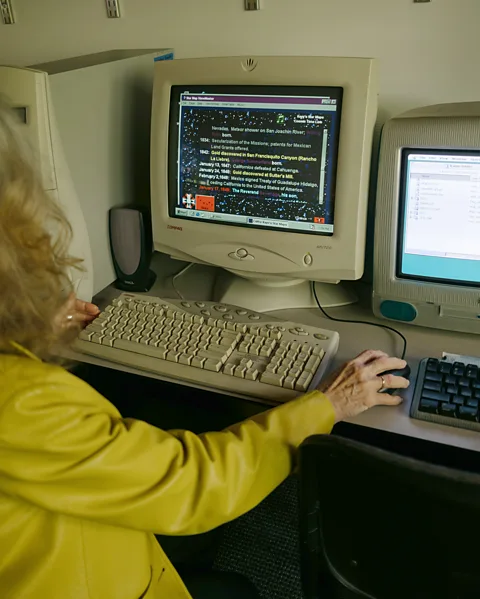

In some cases, however, old computers are a labour of love. In the US, Dene Grigar, director of the Electronic Literature Lab at Washington State University, Vancouver, spends her days in a room full of vintage (and fully functional) computers dating back to 1977. "As soon as people got their hands on computers they started making art," Grigar says, and she's dedicated to preserving it.

In the early days of computing, artists, writers and programs were defining what art and storytelling would mean in the new digital world. Titles like Stuart Moulthrop's Victory Garden or Michael Joyce's afternoon, a story rattled the world of fiction, challenging the very definition of literature by laying out their narratives with links, which allowed for a sort of choose-your-own-adventure style of non-linear writing that set new precedents for the digital age, Grigar says. But she's not just interested in early, experimental e-books. Her laboratory collects everything from video games to Instagram zines.

Ryan Silver/ BBC

Ryan Silver/ BBC"I use an acronym to explain what sets this stuff apart: Pie. It's participatory, interactive and experiential," Grigar says. "You can't take it off the computer and print it or hang it on a wall." Emulators let you run some old software on new machines, but Grigar says important features of these works are often lost in the process. "It's just not the same experience."

Grigar's Electronic Literature Lab maintains 61 computers to showcase the hundreds of electronic works and thousands of files in the collection, which she keeps in pristine condition. Many of the computers look like they were purchased yesterday, with little of the yellowing of plastic cases you might expect from the era of beige electronics.

The only thing missing from Grigar's collection is a PC that reads five-and-a-quarter-inch floppy disks, she says. Despite their ubiquity, the machines are surprisingly hard to find. "I look on eBay, Craigslist, I have friends out looking for me, nothing. I've been looking for six years," she says. If you have one of these old computers lying around, and it still works, Grigar would love to hear from you.

From the beginning, one of the key business strategies that set Apple apart was the fact that for the most part you had to buy Mac computers if you wanted to use Mac software, Ford says. "Apple is also really aggressive about deprecating old products," he says. "But Microsoft took the approach of letting organisations leverage the hardware they already have and chasing them for software licenses instead. They also tend to have a really long window for supporting that software." The approach gave Microsoft a huge advantage in securing business clients.

It's part of why these old Windows machines hang around for so long, Ford says. "Microsoft is just something you get stuck with."

--

For more technology news and insights, sign up to our Tech Decoded newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights to your inbox twice a week.