The 'space archaeologists' hoping to save our cosmic history

Alamy

AlamyThe infrastructure of humanity's journey into space may only be decades old, but some of it has already been lost. A new generation of "space archaeologists" are scrambling to save what's left.

Space is being commercialised on a scale unseen before. Faced by powerful commercial and political forces and with scant legal protections, artefacts that tell the story of our species' journey into space are in danger of being lost – both in orbit and down here on Earth.

Like Stonehenge, these are irreplaceable artefacts and sites that have a timeless significance to humanity because they represent an essential stage in the evolution of our species. They are often also expressions of national pride because of the industrial and scientific effort needed to achieve them. Sometimes they are also memorials to those who died in the course of ambitious space programmes.

They also have another use. Studying these artefacts and sites helps researchers better understand how astronauts interact with new technology, adapt to new environments and develop new cultural practices. The conclusions of researchers can influence the design of future spacecraft and help future space missions succeed.

Can a new generation of pioneering space archaeologists like Alice Gorman and Justin Walsh help save our space heritage for coming generations, and how might their work change space exploration in the future?

On 15 January 2025, the World Monuments Fund's Watch List of 25 threatened heritage sites was released, surprising many by including the Moon, with a focus on the Apollo 11 landing site, in addition to the endangered sites on Earth.

It is rather ironic then, that same day, Firefly Aerospace's Blue Ghost lunar lander blasted off from Kennedy Space Center on board a SpaceX rocket to lay "the groundwork for the future of commercial exploration" of the Moon, according to the company. Firefly became the second commercial company to land without difficulty or damage on the Moon when Blue Ghost safely touched down around 30 miles (50 km) away from the site of the Nasa LCROSS impactor, 90 miles (150km) away from the Soviet Luna 24 probe site, and in the neighbouring lunar sea, vast plains of solidified lava, to where Neil Armstrong's footprints can be found.

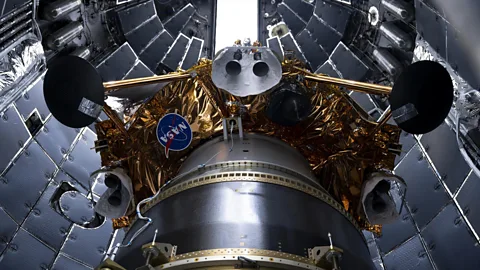

Nasa

Nasa"We don't know yet how to physically operate on the Moon," says space archaeologist Justin Walsh, a professor at Chapman University in California. "Any mission that approaches or enters one of those historic sites is going to have consequences that we can't yet foresee. Whatever precautions we can take, we really must take to keep that damage to a minimum."

But it isn't just sites on the Moon that experts are worried about. Elon Musk wants Nasa to deorbit and possibly destroy the historically significant International Space Station sooner than the space agency intends.

"The window of time we must get procedures and protocols accepted by the international space community is closing," says Alice Gorman, a space archaeologist and associate professor at Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia.

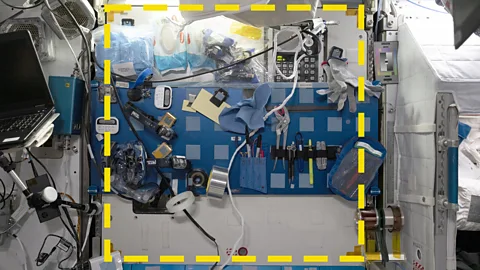

Three years ago, Nasa astronaut Kayla Barron conducted the first ever archaeological fieldwork outside the Earth (and in zero gravity) while orbiting the planet at about a height of 250 miles (400km). On 14 January 2022, she used bright yellow adhesive tape to mark out the corners of 1 sq m (10.7 sq ft) on a science rack in a module of the ISS – like an archaeological trench – and repeated the process in five other locations, ranging from the galley to the toilet.

Archaeology is a "dirt discipline", says Gorman in her book Dr Space Junk v The Universe. Archaeologists dig test pits to reveal a "snapshot" of a site's history. On a space station, that is impossible.

Instead, Barron and her colleagues used digital cameras to photograph each square every day for 60 days. The goal of the exercise was to reveal how these spaces were being used, and how their use changed over time.

"I was here in Los Angeles and Alice [Gorman] was in rural New South Wales in Australia, we were watching Kayla Barron put these pieces of tape out live on Microsoft Teams," says Walsh. "It was like our giant leap."

Walsh and Gorman are leading the International Space Station Archaeological Project (Issap) a joint venture that marks "the first large-scale space archaeology project". Established in 2015, its goal is to study the crew of the ISS, to extend the discipline of archaeology into new worlds and even guide the development of long-duration space missions.

"Space archaeology had always felt rather theoretical," says Walsh. "What would we do if we could go there? But digital technology has changed that.

"There are many more photographs of the inside of the International Space Station (ISS) than of any previous space habitat because its inhabitation coincided with the growth in digital technology."

Alamy

AlamyTheir analysis of these existing photographs of the ISS showed how astronauts personalised areas on the space station to create a visual display that expressed their identity. It showed how astronauts filled "empty space" with – for example – religious icons, mission patches, space heroes and even a geocaching tag, like a fridge door back on Earth.

Last year, the importance of their work for space archaeology led to Walsh's and Gorman's inclusion in the Explorers Club 50 as two of "50 remarkable explorers" changing the world and extending the meaning of exploration.

"We've actually been told by one of the companies designing a private space station that they used our research on how people adapt to living in space throughout the design of the interior of their space station," says Walsh. "That was incredibly gratifying to hear."

For many, the fight to record and save our space heritage began when Beth O'Leary, archaeology professor emeritus at New Mexico State University in the US, published the Lunar Legacy Project (LLP) report in 2000. Its first goal was to treat the entire Moon like an archaeological site and map every single object left by humanity. But, according to O’Leary, this task proved too vast for its limited funding.

"We estimated that at that time [around 2000] there was 100 metric tons of material on the Moon," says O'Leary. "I'd say it's in excess now of 400 metric tons and that's just a guesstimate. So, what is important? Which sites do you focus on?

"We might have chosen the site of the Soviet Luna 2 probe because that was the first human artefact to land on the Moon. Instead, we picked Tranquillity Base because it was the first time humans had landed on another celestial body, and it has an international significance comparable to that of Stonehenge.

"Unable to visit the Moon, we had to really dig in the archives to find out what was left on the lunar surface at Tranquillity Base."

SpaceX

SpaceXThe project has found around 106 artefacts and features left there (a feature is an artefact that cannot be moved, such as each footprint). These include the mundane, such as sample scoops; the emotive, such as footprints; and the poignant – an Apollo 1 Mission patch. The three Apollo 1 crew were killed in 1967 when fire swept through their capsule while still on the launchpad at Cape Canaveral.

There were also surprises. They discovered that medals from two cosmonauts, Vladimir Komarov and Yuri Gagarin, had been left there by the Apollo 11 astronauts. "Their widows had passed on the medals to the American astronauts at the height of the Space Race and the Cold War," O'Leary says. "It's very powerful, isn't it?"

As the LLP website asks: "If this site is not protected, what will be left?"

Space archaeology essentially involves applying archaeological methods and theories to everything related to the era of space exploration. This can range in time from the launch sites of the rockets tested just before World War Two to a present-day drone flying in the atmosphere of Mars. It can also include wider culture, such as the expression of ideas about rockets in children's toys.

Rather than digging in the dirt with a trowel, space archaeologists more often sift through scientific papers or engineering plans. They look for evidence in remote sensing data, satellite images of landers on planet surfaces and space probes in orbit.

"Space archaeology is about putting all this kind of data together and combining it, in a way that an engineer wouldn't, to say something new about an object," says Gorman. "What is the setting or the place of this artefact? How has it fared in that space environment? What does it look like? How would a person experience these kinds of things?

"It's a bit counterintuitive because archaeology is such a physical discipline, that's part of what we all love about it, but we can't often do that."

Firefly

FireflyIt is a natural progression to want to save what you have recorded. But is it real archaeology?

"It's something people have trouble with," admits Gorman. "They say, 'how can this be archaeology?' It's too recent. But when does the past start? According to [science-fiction writer] Isaac Asimov, the past can start a millisecond ago."

In 2010, Beth O'Leary and her colleagues succeeded in placing Tranquillity Base on the California and New Mexico state registers of cultural properties-resources because of the role these two states played in the space programme. Five years later, the International Space Station Archaeological Project was launched.

Then space archaeology started to gain wider recognition. The job of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (Icomos) is to promote heritage conservation and advise the World Heritage Committee on sites to include on its list.

The creation of the Icomos International Scientific Committeeon AeroSpace Heritage (ISCoAH) in 2023, which recognised the threat to archaeological sites on the Moon, "was huge" for the discipline, says space archaeologist Gai Jorayev, a senior research fellow at University College London, who is president of the committee.

Among other subjects, Jorayev studies what he calls the "dark heritage" of the Soviet space programme, such as the people who sacrificed their lives building the Baikonur Cosmodrome in the former USSR.

Many hope that the inclusion of the Moon on the World Monuments Fund's 2025 Watch list will lead to further progress, such as an internationally endorsed list of space heritage sites and a space heritage charter. "So, I would say we were only really, after 25 years, getting started," says Gorman.

But the fate of historically significant spacecraft is even more uncertain.

"There have been ideas of putting the most historically valuable objects into a stable museum orbit around the Earth that is relatively empty," says Walsh. "This could include Vanguard 1, the oldest object now in space."

In January 2025, a paper suggested that Vanguard 1 should be brought back to Earth and exhibited in a museum.

Nasa/ Issap

Nasa/ IssapSimilarly, it can be argued that the Hubble Space Telescope, which has transformed our understanding of the universe, and the International Space Station, the largest spacecraft ever built, should also be saved.

Research suggests that up to 40% of the space station could survive re-entry. "We need to think better about end of life for these craft," he says. "If you can foresee that a mission is likely to be historic, then the preservation of the spacecraft should be part of the calculations."

There is some good news in the battle to save the artefacts that tell the story of our species' journey into space. Archaeologist Thomas Penders can see the top of the Blue Origin rocket New Glenn from his archaeological laboratory at Cape Canaveral. "I can't be there when they're launching but I wish I could," he says.

As cultural resources manager for the US Air Force/US Space Force at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Penders must balance the need for conservation with the needs of the growing commercial space industry. He looks after a 19,200 acre (7,800 hectre) area of Florida that encompasses what he calls the "most significant aspects of the US space programme's history and future ", including the hallowed ground of Cape Canaveral.

Penders spends much of his time consulting with the State Historic Preservation Office on whether it's okay for these historic launch complexes to be reused.

"Blue Origin has taken over Hangar S and they understand the significance of it," he says. "They've been very cooperative with us in maintaining the integrity of the building and hangar."

Hangar S was the home of the United States's first human spaceflight programme, Project Mercury, and Blue Origin's rockets are named after famous Mercury astronauts.

More like this:

• The ocean grave for 264 spacecraft

There are new archaeological discoveries as well. "A contractor working on the Blue Origin launch complex found missile parts and called me in," says Thomas Penders. "What I found is that in the '50s and '60s we were in such a race to develop rockets and put a man in space…missile parts were just thrown over the fence that surrounded the launch pad, and they were still there today."

The commercialisation of space means this is a vital time to preserve space heritage. "These critical and extraordinary moments in the history of humanity deserve our attention, and they deserve a chance to exist into the future," says O'Leary.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram.