What will it take to set up colonies in space?

An ambitious idea for creating giant orbiting homes in space is being resurrected by a think tank. If you think this sounds absurd, it’s worth noting this group predicted travelling to Moon 30 years before it happened.

Imagine a pristine landscape of fertile fields and forests nudging up against the foothills of towering mountains. Rivers meander between prosperous towns dotted across the countryside. You can hear the sound of children playing in parks and gardens. Above them, in a clear blue sky, the Sun catches the wing tips of gliders circling in the thermals.

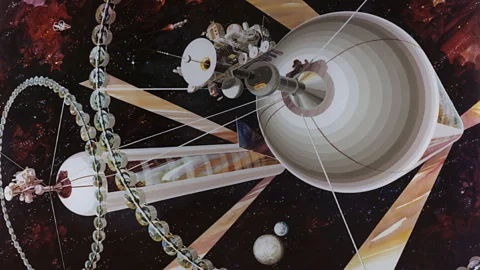

It sounds perfect, but something is not quite right. The scene is unnaturally idyllic, the sky slightly too blue and the horizon more curved than normal. That’s because this world is only 16 miles long, four miles wide and contained in a giant cylinder floating in space.

It’s a space colony concept, drawn up by the late Princeton physicist Gerard O’Neill in the mid-1970s, but his ambitious plan is now being revived by the space think tank British Interplanetary Society (Bis). The organisation has form in championing ideas that are not necessarily as wildly eccentric as they first appear. In the 1930s it came up with a detailed plan for a multi-stage rocket and a manned lunar lander, which looks remarkably like the mission that 30 years later successfully delivered Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to the Moon.

“Back in the 1930s, the major work of the British Interplanetary Society was explaining to the public that exploring space was not a ridiculous idea,” says Jerry Stone, leader of the Study Project Advancing Colony Engineering (see what they did there?). “And what I’m trying to do with the space colonies project is something similar, to show that building a very large space colony is technically feasible.”

O’Neill’s original space colony proposal started out as an exercise for a group of students at Princeton. “Is a planetary surface the right place for an expanding technological civilisation?” he asked them. After a few months, and a great many calculations, the answer came back a resounding “No”. This got him interested in alternative human habitats beyond the Earth, and he conceived giant rotating spaceships containing landscaped biospheres housing up to 10 million people.

“There are two big advantages of constructing a colony in space rather than on a planet,” explains Stone. “You have the Sun’s energy 24 hours a day, so you can concentrate that energy to melt materials or use it to generate power, and you can rotate the habitat to create whatever gravity you want.”

These solar-powered colonies would be positioned at Lagrange points, stable areas in space where gravitational forces effectively balance each other out. They therefore wouldn’t need their own propulsion systems. Travelling to them would take weeks, compared to the months required to get to Mars.

Space odyssey

O’Neill’s detailed plans for his colonies appeared in the journal Physics Today, where he thought through many of the practical considerations. The basic structure of the habitats, for instance, is designed around a hollow tube made of metal and glass. Within, a plant-rich landscape stretches around the walls, broken up with giant windows into space.

There would be a semi-natural water cycle including clouds, and oxygen would be recycled by plants. These climate-controlled living spaces would be like the most beautiful areas of Earth, with a rich mix of disease-free flora and fauna. Maybe even a selection of endangered species.

Rather than living on the outside of a sphere as we do on Earth, colonists would settle around the inside. With the cylinder rotating, they would experience an artificial gravity effect. Only if they moved away from the cylinder’s walls, towards its central axis would they feel weightless. In this way, the inhabitants of Earth 2.0 really would be able to fly.

O’Neill deliberately designed the structure using existing 1970s technology, materials and construction techniques, rather than adopting futuristic inventions. The hollow cylinder, for instance, was based on steel and aluminium. After detailed calculations, he claimed his concept was feasible at the time he published it.

Stone is bringing these plans up to date using today’s technologies. Rather than building the shell from aluminium, for example, Stone argues tougher and lighter carbon composites could be used instead. Advances in solar cell and climate control technologies could also be used to make life easier and more comfortable in human space colonies.

One of the biggest theoretical challenges O’Neill faced was the effort and cost of construction. That, says Stone, will be solved when a new generation of much cheaper rocket launchers and spaceplanes has been developed, such as the UK-built Skylon. Using robot builders could also help.

“Ninety per cent of the material to build the colonies would come from the Moon,” says Stone. “We know from Apollo there’s silicon for the windows, and aluminium, iron and magnesium for the main structure. There’s even oxygen in the lunar soil.”

Designs for life

Let’s assume it is doable, what would be the cost of such a vast human undertaking? “Good question,” admits Stone. “The likelihood is that it would be started off by a consortium of companies and we hope that would become an international group.” Alternatively multi-billionaires with an interest in space such as Jeff Bezos of Amazon or SpaceX’s Elon Musk might take the lead.

But the practicalities of building a colony in space are only part of the story. Perhaps even more important and complex, are the societal considerations. What sort of laws and government should it have? A democracy or a billionaire’s fiefdom? Perhaps it would be the ultimate offshore tax haven. At first the colonists may model their political, legal, economic and social structures on those back home, but eventually they are likely to be adapted to the new environment. Stone has drawn up a three-page list of fundamental questions of this kind that his study group plans to address.

There is indeed a lot to think about and it’s easy to knock these sorts of big, visionary ideas. However, I’m not alone in believing that if humanity is to survive we will one day have to leave the Earth. A giant space habitat might be just the stepping-stone to the stars that we need.

If you would like to comment on this article or anything else you have seen on Future, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.