Six Nordic paintings that can help us rethink winter

Munchmuseet/ Halvor Bjorngard

Munchmuseet/ Halvor BjorngardWinter isn't all bad – these "sublime" landscapes of the frozen North from the turn of the 20th Century offer us a way into resilience – and an "acceptance of the seasonality of life".

With its bare trees, long nights and icy temperatures, it's perhaps unsurprising that, culturally in the Northern Hemisphere, we seem so conditioned to complain about winter. Yet, as the author Katherine May points out in her 2020 book Wintering, winter is also a valuable time for rest and retreat. "Winter offers us liminal spaces to inhabit," she writes. Its "starkness", she argues, re-sensitises us, and "can reveal colours that we would otherwise miss".

Finnish National Gallery/ Alteneum Art Museum

Finnish National Gallery/ Alteneum Art MuseumFor Nordic countries, where, in some regions, the season can last more than six months, making peace with winter is a necessity, with concepts such as the Norwegian friluftsliv (embracing the natural world) and the Danish hygge (hunkering down with simple comforts) offering fresh perspectives on cold weather.

At the turn of the 20th Century, the frozen North – with its vast fjords, mystical boreal forests and radiant light – became a powerful muse for artists such as Hilma af Klint, Edvard Munch and Harald Sohlberg. These artists immersed themselves in these cold climates, and developed a specifically Nordic style of painting imbued with their emotional responses to the landscape. Around 70 of these intensely atmospheric, expressionist works by artists from Scandinavia, Finland and Canada are being showcased in a new exhibition, Northern Lights, a cross-Atlantic collaboration that debuts at the Fondation Beyeler in Basel, Switzerland, before travelling to New York's Buffalo AKG Art Museum in August.

It was natural that these painters should be drawn to these wintery scenes, Ulf Küster, the exhibition's curator, tells the BBC. "In Nordic landscapes, snow is a very dominant factor of life from October to late April… It's just this massive presence of white and nature and wilderness and vastness that really defines this landscape, and I think these painters have found a very interesting response to that." This burst of Nordic landscape painting was also a response to the changes that the painters perceived as a result of population growth and industrialisation. "There was a big desire in the late 19th Century to return to pure nature and the simple life," explains Küster. "You had these highly industrialised countries and pollution, and the pureness of white snow must have been quite a contrast."

Private collection, courtesy of Galleri K, Oslo

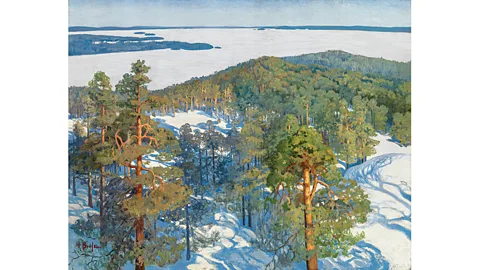

Private collection, courtesy of Galleri K, OsloMany of these northern regions were comparatively untouched by change, and featured vast, unpopulated vistas that were inherently painterly. Even today, Norway has a population of just 5.5 million, but a length of around 1,600km; while around three-quarters of Finland is still forested. To convey this scale, these paintings often adopt unconventional compositions where the view appears to stretch beyond the canvas. They are "boundless", says Küster. "They don't have borders". This is reinforced by the bird's-eye view adopted in works such as View from Pyynikki Ridge (1900) by the Finnish artist Helmi Biese. "It's as if the artists have used a drone," remarks Küster.

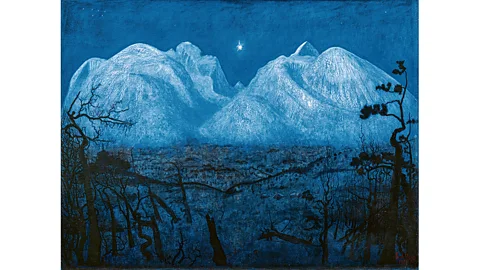

The height and scope of these unpopulated views also convey a sense of isolation and loneliness. Harald Sohlberg, whose luminescent 1914 version of Winter Night in the Mountains is widely considered to be the national painting of Norway, wrote: "The longer I stood gazing at the scene, the more I seemed to feel what a solitary and pitiful atom I was in an endless universe… It was as if I had suddenly awakened in a new, unimagined and inexplicable world… Above the white contours of a northern winter stretched the endless vault of heaven, twinkling with myriads of stars. It was like a service in some vast cathedral."

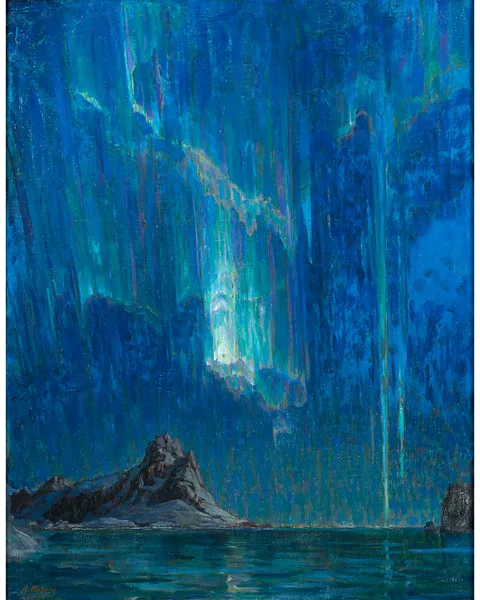

It was this search for solitude that doubtless drew the Swedish artist Anna Boberg to the Norwegian archipelago of Lofoten, a remote location steeped in Viking folklore and, according to her 1901 memoir, "the apotheosis of Arctic beauty and wilderness". It was here, dressed head-to-toe in seal and reindeer fur, that she produced her Northern Lights (1901) painting, most likely sketched en plein air. In a commanding scene that speaks to the Romantic notion of "the sublime", prismatic streaks of light descend from the heavens dwarfing the snowy landscape.

Anna Danielsson/ National Museum, Stockholm

Anna Danielsson/ National Museum, StockholmBoberg's awe when confronted with this dazzling wintry world with its unique light is clear. "What really drove these people was to find a response to the extremities of nature – the very essence of snow, winter and ice." explains Küster. To achieve this, they would "get as close to nature as possible", he says. Far from hiding from the harsh winter, Boberg and her contemporaries immersed themselves in the landscape. "They are painters who really wanted to paint the experience, to feel the extreme temperature and the snow blindness," says Küster. Munch, he continues, had outdoor studios, and would leave his paintings outside "just to let nature test them", while some of the Canadian painters would paddle out on to lakes and paint from their canoes.

Beautiful and barbaric

Inland, the boreal forest embodied the enchanting duality of these landscapes, which were both beautiful and barbaric. The dark, primeval forests became an emblem of foreboding in Nordic folklore and myth – places where you could get lost, and that concealed unknown dangers. The Nordic winter landscape fed the fairytales of the Danish author Hans Christian Andersen. "Below them the wind blew cold, wolves howled, and black crows screamed as they skimmed across the glittering snow," he writes in The Snow Queen (1844). "But up above, the moon shone bright and large."

Hans Thorwid/ National Museum

Hans Thorwid/ National MuseumThis storybook quality can be seen in Winter Moonlight (1895) by the Swedish painter Gustaf Fjaestad. Here, his clever use of pointillism makes the snow appear to glitter, while the hand-like branches of the dense, drooping trees look poised to come alive. In The Lair of the Lynx (1908), Akseli Gallen-Kallela, a Finn, also revels in this tantalising, darker side to the landscape, inviting us to scan the canvas for the dark places beasts may be lurking, and to follow their tracks in the snow.

Notable, also, is the power and movement he gives to the snow as it winds in thick layers around the trees. "The brushwork of this painting meticulously reacts to the layers of snow," says Küster. "It's snowing, then it's freezing, there might be some sun and there's a little thaw, and then there's freezing again and more snow comes on top." The painter is clearly entranced by the snow, the layers of paint telling the snow's story. The visual effect, observes Küster, is "like a sort of wedding cake".

Courtesy of the Faurschou Collection

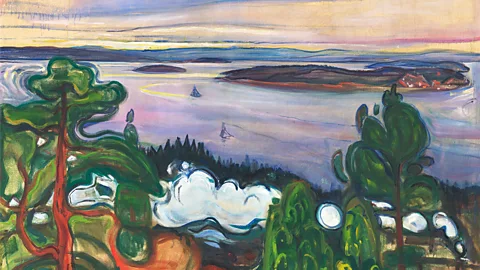

Courtesy of the Faurschou CollectionAs well as drawing inspiration from the landscape's mythical associations, these artists participated in their own myth-making, expressing – through their own strong emotional responses to these unspoilt regions – an often idealised view of the Nordic winter. Some, such as Edvard Munch, nevertheless hinted at the changes threatening these serene expanses. During the winter of 1900, he stayed in Nordstrand on the banks of the Oslofjord. Here he painted his now-famous rendition of its serene waters reflecting a magnificent sky of pink, blue and yellow. But this picturesque, swirling scene, foregrounded by pines, is interrupted by a bulbous trail of white paint, denoting, not snow this time, but, as the title makes clear, Train Smoke.

"When we look back at the landscape works of Gallen-Kallela and Biese, we are reminded of how much of the environment has changed in the intervening century," writes Anna-Maria Pennonen in her essay Changing Landscapes in the exhibition catalogue. "The Baltic Sea no longer freezes every winter, and the period when the ground is covered with snow in Helsinki can be very short, perhaps only a few weeks instead of months." As for the magnificent boreal forest, it continues to be threatened by logging and agriculture.

Recognising the mutability of these environments now adds a powerful new dimension when a modern audience engages with these 100-year-old works. "They ask us to think about the enchanting image of the forest in relation to its past and current transformation, as well as in relation to our own part therein," writes Helga Christoffersen in the catalogue. The works invite feelings of nostalgia and melancholy, and our appreciation that they are endangered only amplifies their beauty and psychological intensity.

Munchmuseet/ Halvor Bjorngard

Munchmuseet/ Halvor BjorngardDanish artist Jakob Kudsk Steensen, born in 1987, addresses this issue of climate change in Boreal Dreams (2024), an interactive, immersive work and online experience, commissioned for Northern Lights. The work uses virtual reality to connect past, present and future boreal ecosystems. It takes visitors on a journey into five imagined futures for the boreal forest, marrying technology with environmental data to create a visceral experience of nature. Yet, however bleak the future seems, raw nature – these works suggest – can offer something transcendent. "We like to think that it's possible for life to be one eternal summer," writes May in Wintering. "But life's not like that." By confronting and reframing winter, as these artists do, we can accept the seasonality of life, and cope better with the dark periods of our life. "Winter had blanked me, blasted me wide open," she declares. "In all that whiteness, I saw the chance to make myself new again."

Northern Lights is at the Fondation Beyeler in Riehen/Basel in Switzerland until 25 May and at Buffalo AKG Art Museum, Buffalo, New York, from 1 August 2025 to 12 January 2026. The accompanying catalogue, edited by Ulf Küster, will be published by Hatje Cantz on 13 February.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.